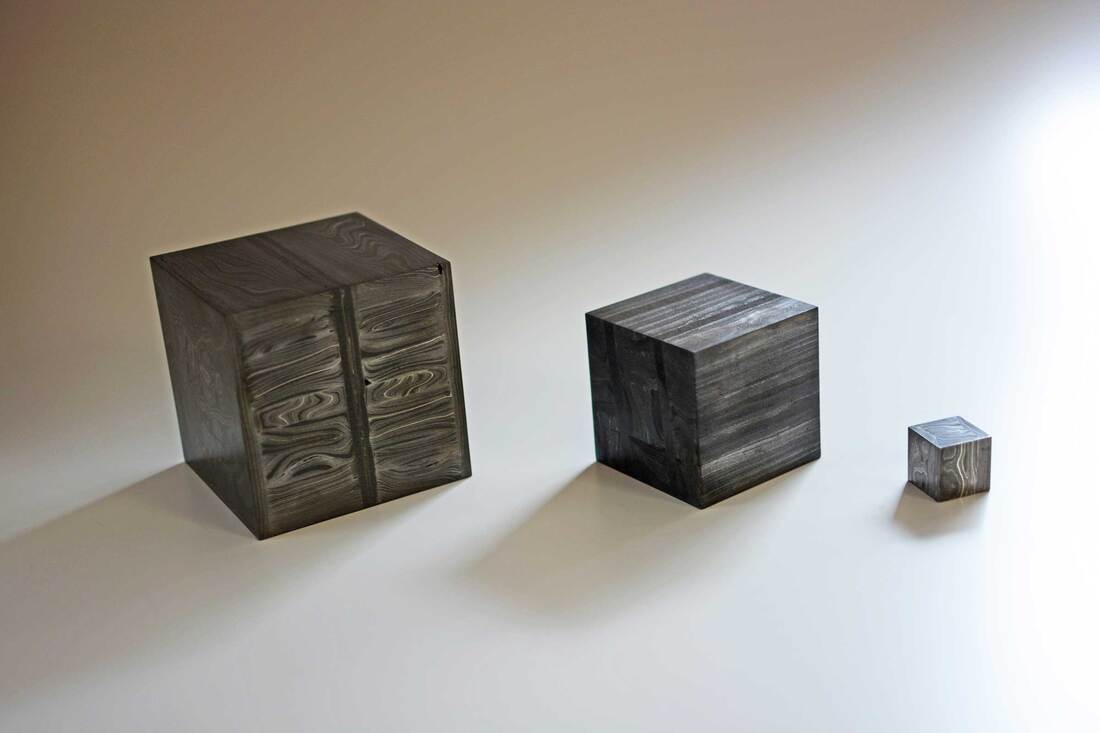

In the rural village of Kanagawa, an hour drive from Tokyo, in the midst of lash rice fields, I have visited the studio of metal artist Kosuke Kato. A graduate from both Tamagawa University and Hiroshima City University, 31-year old Kato, who grew up in this village, has rediscovered, reinvented, and practiced the medieval art of Damascus steel. Traditionally utilized to craft swords and blades, Kato has landed that unique medium and technique to create his art, crafting minimalist, abstract contemporary objects.

Kato was a great host and he explained to me the labor-intensive, somewhat mysterious process, which has come to capture the imagination of generations of craftsmen creating weapons of the highest quality, that are flexible and hard at the same time. Invented in India in ancient time, created of wootz, a type of steel which became popular in the 3th century, it was practiced in the Near East where it was traditionally utilized to create swords adorned with patterns reminiscent of Damascus textiles. To create the material, he is folding and melting together a variety of alloys, particularly steel and iron in charcoal under reduced oxygen, allowing the metal to absorb carbon. This process can take up to thirty days, and when it is ready, the metal is bended to the desired form, Kato deeps the object in bath of chemical liquids, which allows the special pattern to enhance. I have found Kato’s commitment to the method impressive. He represents the new Japanese artists devoting their lives to a single traditional craft, while landing its allure to creating contemporary art.

Kato was a great host and he explained to me the labor-intensive, somewhat mysterious process, which has come to capture the imagination of generations of craftsmen creating weapons of the highest quality, that are flexible and hard at the same time. Invented in India in ancient time, created of wootz, a type of steel which became popular in the 3th century, it was practiced in the Near East where it was traditionally utilized to create swords adorned with patterns reminiscent of Damascus textiles. To create the material, he is folding and melting together a variety of alloys, particularly steel and iron in charcoal under reduced oxygen, allowing the metal to absorb carbon. This process can take up to thirty days, and when it is ready, the metal is bended to the desired form, Kato deeps the object in bath of chemical liquids, which allows the special pattern to enhance. I have found Kato’s commitment to the method impressive. He represents the new Japanese artists devoting their lives to a single traditional craft, while landing its allure to creating contemporary art.

All images from Kato’s first and second solo exhibitions, courtesy Yufuku Gallery.