Making In is an invitation-only annual gathering, taking place at Joseph Walsh Studio in Kinsale, Ireland. That special program, taking place in a September weekend, comes to celebrate the significance of making as a key aspect of contemporary culture, In recent years, it has become a key platform for creative voices, who are invited to share their stories of making art, architecture, design, and craft. I was one of the 100 lucky invitees this year, and spent three magnificent days, meeting the most extraordinary and passionate people, leading voices in their fields in a magical weekend, generously hosted by Joseph Walsh.

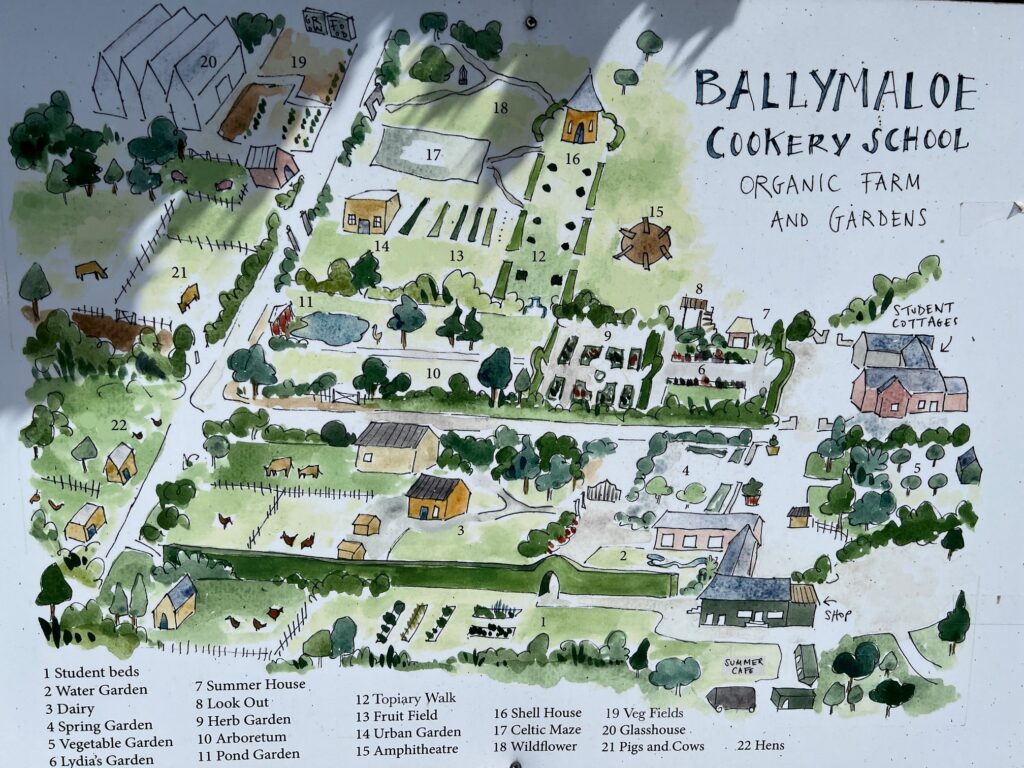

Focusing on the role of the maker in local, national, and international communities, Making In allows us to consider the importance of retaining, preserving, and passing on inherited skills and knowledge, and the cultural and economic value of craftmanship today. The event started with the most delicious lunch at the the famed, award-winning Ballymaloe Cookery School, which pioneered the Slow Food Movement and Farm-to-Table cuisine in Ireland. We were invited to a tour of the 100-acre organic farm, where we learned about food and how it is produced sustainably, from the stars Dorina Allen and her brother Rory O’Connell who have spent the last four decades perfecting their mission.

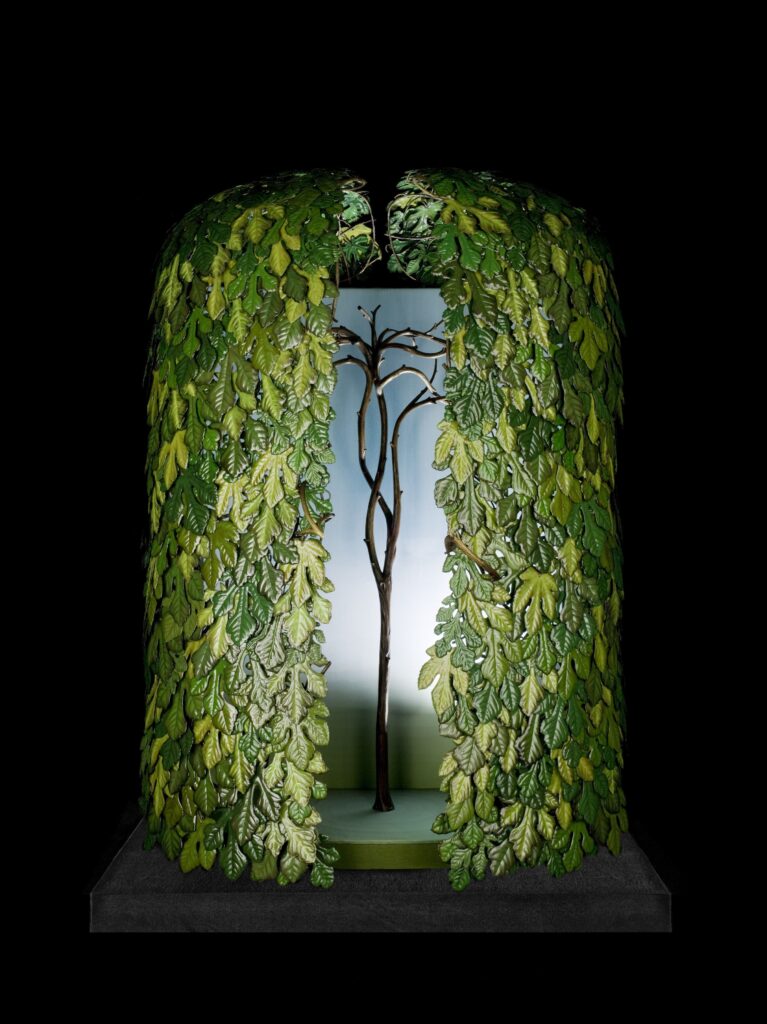

The theme of Making In 2022 was ‘Time,’ exploring time to make and the time to appreciate making; the timelessness of quality and the relationships that endure through time and the process of craftsmanship, modertated by Glenn Adamson. Speakers came from all over the world and the list included Joe Hogan, the Irish master basket-maker, who uses local willow, larch, catkins, and bogwood to craft the most magical sculptural baskets, evoking the connection between the material and his place; O’Donnell + Tuomey, the husband-wife award-winning architects, responsible for the upcoming Stratford Waterfront Masterplan; New York architects Tod Williams and Billie Tsien, the creators of the Obama Presidential Center in Chicago’s South Side; Tord Boontje, the Dutch designer whose work I have followed for years, but whom I have met in person for the first time, and loved learning about his multifaceted work for Alexander McQueen, Target, Moroso, and many other firms; ceramicist Peter Lane, whose architectural walls and fireplaces in clay have come to transform some of the world’s best interiors; Imogen Stuart, who at 95, is still considered Ireland’s most admired sculptor; Satoru Ozaki, whose work in stainless steel I have admired for years, and who spoke about his difficult journey from starving artist to the world’s stage, attending the event with his dynamic gallerist Wahei Aoyama, who is credited for brining the new voice in Japanese art to international recognition; Philip Treacy, the Irish haute couture milliner, who was famously described by Vogue magazine as the greatest living milliner, and many fascinating people who have turned this weekend into a spectacular experience.

I was asked to introduce Mira Nakashima, who spoke about the essence of woodworking at the workshop in New Hope, PA, and here is my introduction:

“I am honored to introduce Mira Nakashima at this event, bringing closure to a journey that began 35 years ago. Mira is a trained architect and is both the president and creative director of George Nakashima Woodworker: the studio founded by her father in the 1940s in New Hope, Pennsylvania. She worked hard to get where she is today, and her life has been interwoven with that of the studio. Mira started working part-time for her father and mother in 1970 while raising three young children and being pregnant with the fourth. She eventually became her father’s assistant until he died in 1990.

She was born in Seattle Washington and spent the first few months of her life imprisoned in a relocation camp located in Idaho with her parents, along with many other Japanese Americans who were detained after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Despite being born during one of the darkest chapters in the history for the Japanese Americans, she has managed to become a true pride to the country.

Mira’s role at the studio has been critical to sustaining it as the only studio of the glorious craft movement, to continuously existed since the mid-20th century. In addition, she is responsible for turning the studio into one of the most successful stories in the narrative of American modern design. To George Nakashima furniture was not about simply chopping wood and putting the pieces together, but a personal lifestyle that combined a love for nature, yoga practice, and spiritual living, which lead to him crafting some of the most memorable and magical pieces of furniture in the history of design. Mira has preserved her father’s unique philosophy of giving the tree another chance—a second life—through furniture design. She continues to shape and perfect her craft every day with endless love and care, and currently employs a staff of 16 people, 10 of whom are in the woodshop making furniture.

For me, this journey began on the hottest day of the summer of 1987, when I first crossed paths with the Nakashima family. I was pregnant with my twin boys when I visited the studio for the first time; this day came to change my life. I clearly remember George Nakashima sitting in the showroom in the same way a guru talking to clients, surrounded by the most beautiful pieces of furniture I had seen up to that point. This was the first time that I was exposed to design with purpose and intent. You can read all the books and attend all the designer showcases, lectures, and exhibitions you want, but when you go to Nakashima studio, you begin to truly understand design. He made furniture to live with, not just to be a showcase of taste, class, or aesthetics. I became a fan and collector and of Nakashima’s pieces, which have brought a sense of harmony and spirituality into my home and become a part of our family.

I want to reveal something you probably don’t know about Mira: during the time she was attending high school, girls were not allowed to take shop class. She was in the first-class graduates from Radcliffe to receive Harvard degrees in 1963. She carried her infant son to her graduation, receiving a master’s in architecture from Waseda University in Japan, where few women were enrolled. She did not speak, read, or write Japanese, nor did she know how to draft by hand when she started two years earlier, and depended heavily on her classmates to help her through the program, something for which she is still grateful.”

A weekend filled with passion, knowledge, and so much fun. It was about material culture, archtiecture, and design, but ultimately, about connections and life experiences. Thank you, Joseph Walsh for including me in this memorable event.

What a privilege it must have been to attend this event. Thank you for sharing with us.