Alexander von Vegesack, venerable collector

and founding Director of Vitra Design Museum.

Ulrich Fiedler, this week’s guest on Collecting Design: The Legends, possesses a highly sought-after expertise that encompasses much more than the furniture typically found in shops or even in other galleries. Rather he excels at spotting and appraising those exceptional, rare pieces that are destined for museums and the homes of the world’s top-tier design collectors. His unique specialization is the original furniture that was created in the interwar years by the preeminent figures of the Modern Movement—Le Corbusier, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Gerrit Rietveld, Marcel Breuer, Eileen Grey—those who created the most iconic works of the 20th century, who revolutionized design theory, and who established the benchmarks against which design has been judged ever since.

Although born from a desire to change the world by raising the living standards of millions, the avant-garde modernist designs that Fielder represents rarely manifested the creators’ utopian dreams of machine-driven mass production. Instead, these early 20th-century designs, Fiedler told us, were quite limited—even smaller than we likely imagined. In many cases, he revealed, the fabrication did not go beyond the first stage of prototyping.

Fiedler knows every part, every screw, the fabric, the metal, the wood, the fiber of these icons, from Breuer’s Wassily Chair and Brandt’s Ashtray to Hartwig’s emblematic chess set, Rietveld’s Beugel Chair, and Místecký’s tapestries. And he knows them by heart, the result of years and years of researching, handling, discovering, and examining some of the most treasured designs ever created.

The pieces you’ll find at Fiedler’s Berlin gallery belong to the rationalist tradition and embody the optimism of their time. Within the context of Europe’s expanding prosperity in the 1920s, a generation of architects and designers experienced a moment’s hope that war and destruction belonged to the past, that an ever improving future could be built on the promise of progress. For this future, they imagined homes for a “New Man,” for which they developed new types of furnishings, lighting, tableware, and other domestic goods that were unisex, hygienic, multifunctional, and light. They used the newest methods and the most innovative materials available, which enabled them to capture the zeitgeist of the day.

Fiedler began our conversation in the atelier of Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier, whose concept of homes as “machines for living in” found form in the furniture he developed with guidance from his assistant Charlotte Perriand for the 1929 Salon d’Automne. Thanks to their purist, mechanical character, they were a perfect match for the Corbusian architectural aesthetic.

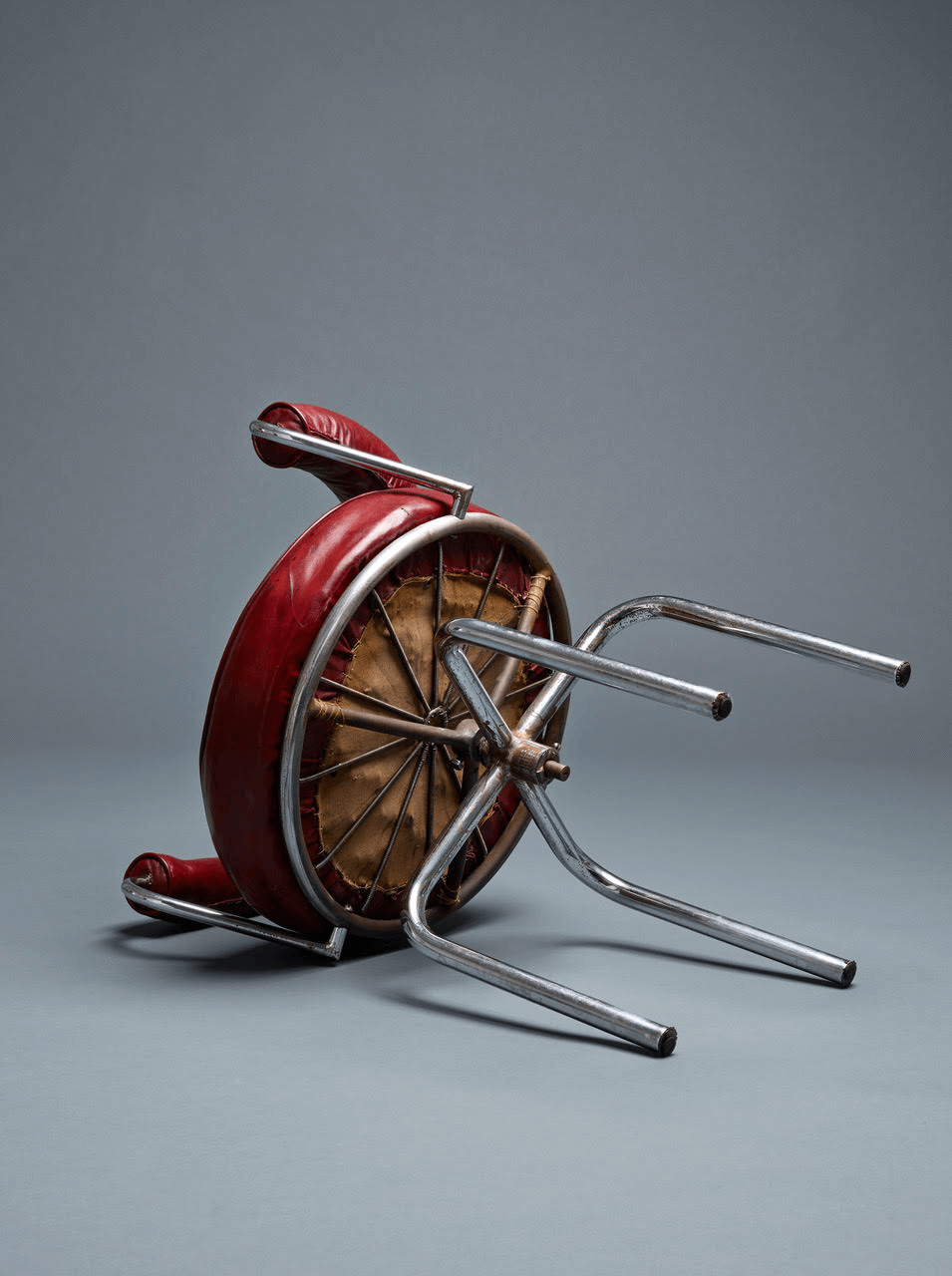

Fiedler also discussed the history-making models that the Le Corbusier atelier created in 1928: the Fauteuil Grand Confort (Grand and Petit), Fauteuil à Dossier Basculant, Chaise Longue, Siège Tournant Fauteuil, and Siège de Salle de Bain. We learned that all prototypes were handcrafted in small Parisian workshops out of tubular steel and found metal parts, including bicycle wheels. Each was different, and each was marked by the hand of its fabricator.

In her memoir, Perriand revealed that she first offered the production of this collection to Peugeot, a natural choice for steel furniture since the automotive manufacturer already produced the type of bicycle parts utilized in the prototypes. But the production ended up with Thonet-Frère, a branch of the world’s largest furniture company back then. Despite issuing two catalogues, patenting the designs, and conducting an extensive marketing campaign that highlighted Le Corbusier’s name, Thonet found little success with the collection; it quickly became clear that steel furniture was just too expensive to compete with conventional wooden furniture.

From the 1930s, Fiedler explained, the Chaise was produced in a limited number by a company in Zurich until Le Corbusier’s lover, Heidi Weber, signed a deal in 1964 with Italian manufacturer Cassina, which continues to produce designs from the collection to this day. Each one of these fabricators, we learned, had a different take, method, and variation, which makes authentication an easy task for experts like Fiedler.

Fiedler shared many more stories about the pioneers of modernism and their machine-age designs that could only be fabricated by hand. But the most striking lesson we learned from him was about the power of connoisseurship to deeply enhance the design experience.

Above: Mies van der Rohe’s Small Desk, circa 1930, and Side Chair MR10, 1927. Photos © Galerie Ulrich Fiedler. This article appeared this morning in The Forum, the magazine of Design Miami/. Registration to Collecting Design: The Legends.