While Americans perceived the words modern and vernacular as incompatible during this time (see the ‘Kitchen Debate’), in Brazil they complemented each other, formulating the foundation of everything that was ‘modern.’ Each and every design and architecture professional who contributed to the story of Brazilian mid-century modernism had recognized the significance of connecting to the local culture, and therefore, it manifested in a distinctive and national character.

Both immigrants, who brought with them the philosophy of the Modern Movement from Europe, and non-immigrants realized that the country was emerging from colonialism, becoming independent and thus in a need for a genuine visual expression. It was the golden age of Brazilian design and architecture, just before the military government came into place and ruled the country for two decades.The lecture last evening traced the variety of ways in which the design community connected with the vernacular. For furniture designers, such as Sergio Rodrigues and Jorge Zalszupin, who mastered t

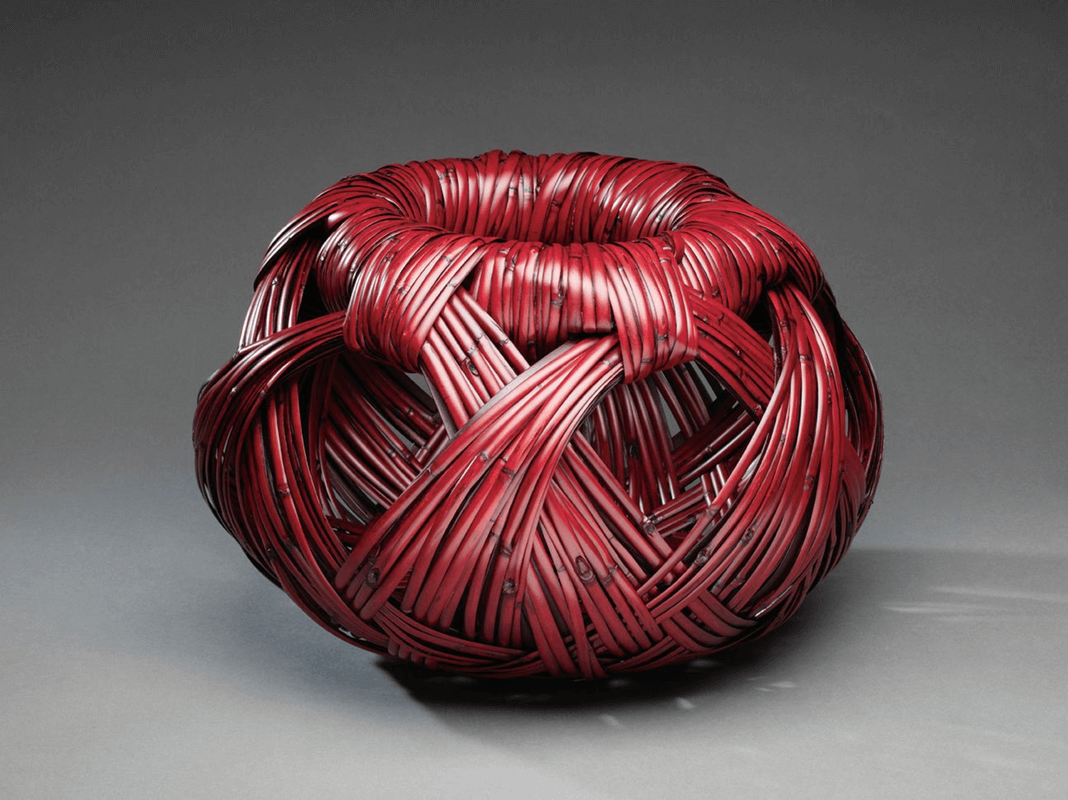

he reinterpretation of colonial forms, it was about using rich and textured tropical hardwoods and woven leather, creating pieces that are laidback in reflecting the love for relaxation. For those who built housing, whether architects, contractors, or unskilled laborers, it was about applying available, mostly poor materials to modernist principles, largely inspired by Le Corbusier. For Roberto Burle Marx, the legendary landscape architect, it was about rediscovering indigenous species of plants, organic schemes that did not rely on any foreign heritages, making gardens ecological, local, and unique to Brazil. And for those who created Hvaianas, the Brazilian brand of flip-flop sandals, patented in 1962, it was about making a consumer product for the local beach lifestyle.

When Oscar Niemeyer designed his masterpiece Brasilia, the new capital city that moved from Rio de Janeiro, he created white, pristine, sculptural buildings in the modernist vision. Yet, unlike the geometry of orthodox modernism, his buildings were curvy like the local dance; biomorphic like the local landscape; sensual like the country’s relaxed lifestyle. Brazilian design culture of the mid-century years embodied the term ‘Modern Vernacular.’ Above: ‘Pedregulho,’ by Affonso Reidy and Carmen Portinho, Rio de Janeiro, 1947.

Next Friday, we will begin with the second part The Story of Modern Design. Registration is open.