If she had lived during the age of social media, she would certainly have been one of the world’s most powerful influencers; an arbiter of taste, defined by her delightful eccentricities. Her advice would have been embraced by millions, and her homes—a luxury apartment on Park Avenue in New York, a house in London, and a penthouse in a mansion on the Île Saint-Louis in Paris—would be hailed as having the finest interiors. She would have assimilated well among today’s influencers, commissioning photographs of her homes, her art, and endless portraits by the leading photographers of her time. She knew branding and understood well the power of photography to turn a private figure into a public one.

But Helena Rubinstein (1872-1965) had risen to fame in another era, and when she came to define style, collecting, and the role of women in the world of business, magazines were the primary means of promotion. The Polish-American businesswoman was the founder of the successful international cosmetics empire that bore her name. The story of the ‘Madame’ (as she was called by her employees), was told by many, and her rise from poverty to the world stage, as well as her role as an entrepreneur, philanthropist, and art collector, have all been fully entrenched in 20th-century culture.

A new book, Helena Rubinstein, Madam’s Collection (edited by Helene Joubert and published by SKIRA), tells the fascinating story of Rubinstein’s exceptional art collection—the best of its kind ever assembled; a collection which, once dispersed, could never be duplicated. What set this book apart from other publications on the subject is twofold: first, the posthumous focus on the journey of the collection; and second, her role in the history of women art collectors of the 20th century.

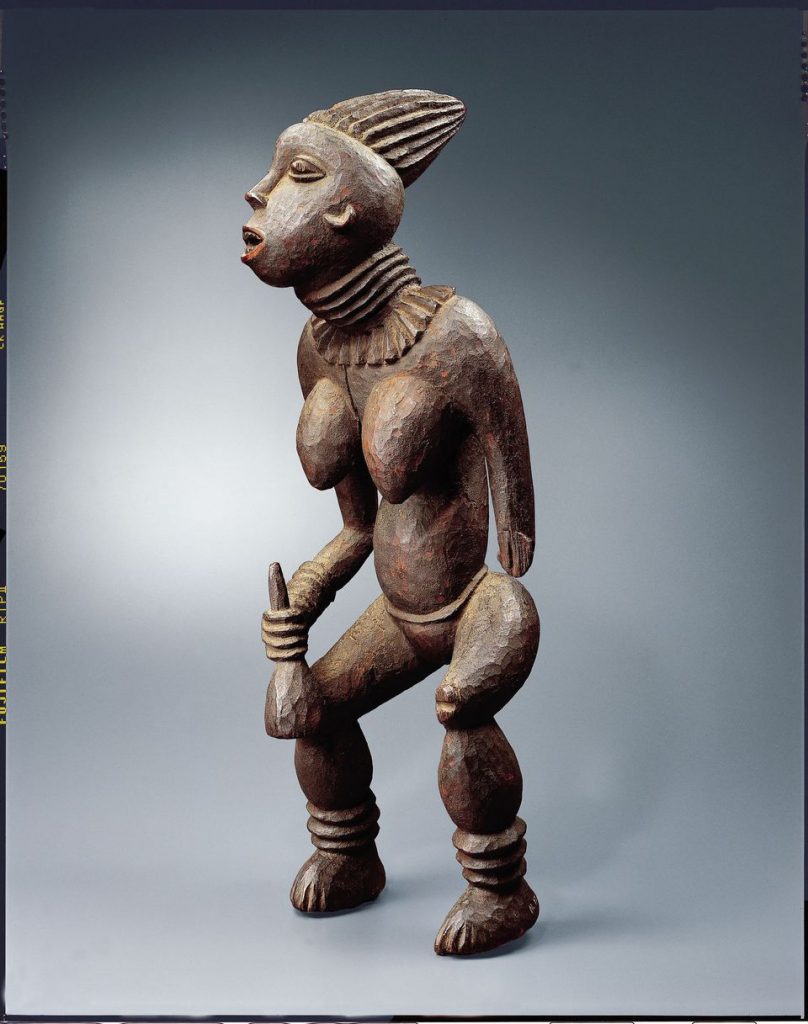

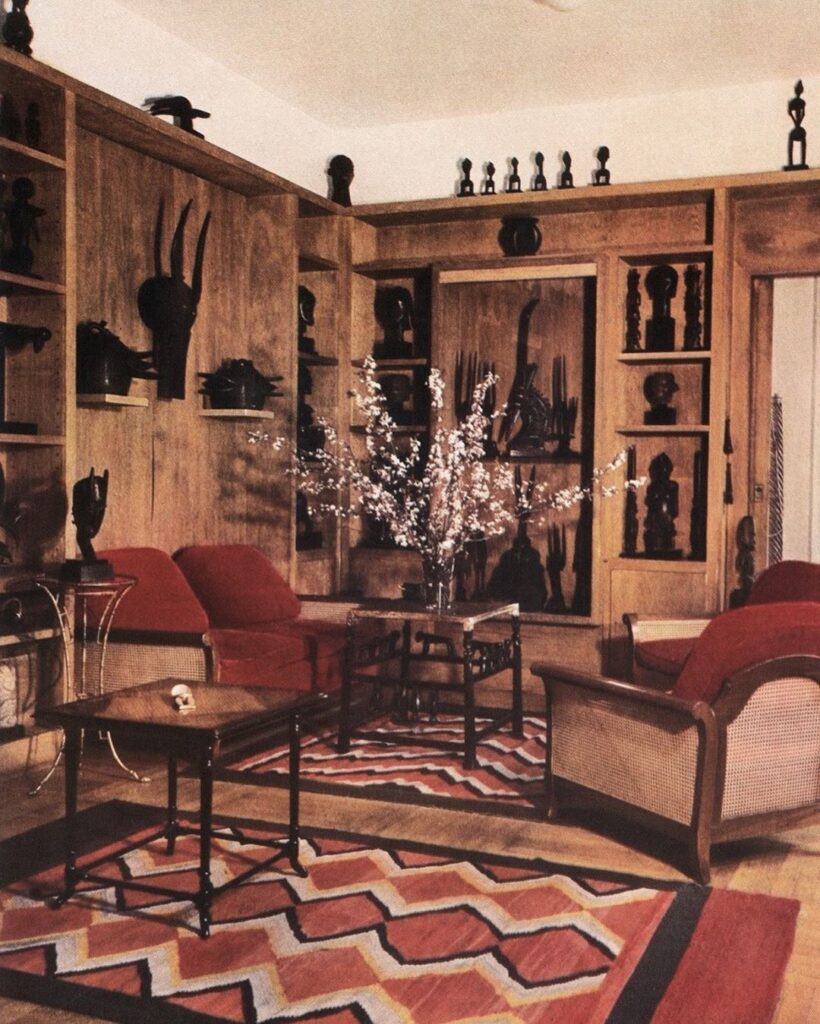

Rubinstein famously commissioned Salvador Dalí to paint murals in her dining room; and her homes were filled with baroque Venetian furniture, and the works of avant-garde art by Brancusi, Matisse, Picasso, Chagall which she had acquired directly from the artists. But none of these masterpieces could compare to the vast collection of African and Oceanic art that demonstrated Rubinstein’s taste for the Primitive. It is through these artifacts that she was able to recognize her own taste; her own personal identity. The collection was sold by Sotheby’s in 1964, a year after her death, setting many records. The pieces from her collection continue making headlines and are considered among the best African artifacts in existence.

The most expensive of all was The African Queen, which she lent out for the famed Bangwa Negro Art Show at MoMA in 1935, where it was photographed, along a with nude model, by Man Ray. It was purchased by California dealer Harry Franklin for $29K, and later fetched $3,400,000 when the Franklin Collection was sold at Sotheby’s in 1990. Hélène Joubert, head of the African heritage unit at the Musée du quai Branly in Paris, investigated Rubinstein’s collection and was able to identify half of her primitive artifacts. The book is timely, emphasizing how 20th-century women gained power, wealth, and influence through art collecting, and illuminating the interest in women studies. When Rubinstein started collecting in 1909, she was a pioneer—partly due to her gender—but also because of her unconventional taste (we learn from the excellent essay by Julie Verlaine). The book also elucidates her love for the tribal—for black art—which mirrors the enormous renaissance and interest in black pop culture and art in 2020. Yet, the greatest lesson we learn from this book is that taste has to grow from within, and that, once a genuine taste is forged, it becomes a mirror of oneself. Rubinstein went against the grain. When the entire world went modern, she sought baroque; when people sought to move toward casual interiors, hers were formal. Later, as modernism developed, she was not afraid to express a taste that was opulent and flamboyant.