When Paris was the cradle of Art Nouveau in fin de siècle France, Hector Guimard (1867-1942) emerged as one of its leaders. While his contemporaries depicted flowers, he illustrated swirling stems; while they sought to recreate nature in a realistic mode, he abstracted it—flawlessly bringing his era into modernism. Guimard was not only a talented artist, but also a brilliant businessman. When the work of his and his Art Nouveau cotemporaries Louis Comfort Tiffany and Émile Gallé became dated, some of them went bankrupt, as the popularity of the style began to wane. But Guimard emerged as a modernist—like a phoenix, regenerated and reborn. Perhaps not as successful as his contemporary Rene Lalique who emerged with his art glass empire, but as an architect of public housing. Whether they lived in Paris, or New York, Barcelona, or Brussels, or Turin, Art Nouveau artists were all on a similar quest: to find new and modern language in the arts (New Art), and they found it in the sinuous organic lines and shapes seen in nature. Guimard, however, was more visionary, and succeeded in evolving into the new century. He is one of the most intriguing figures in the history of design, so the new monograph exhibition Hector Guimard: How Paris Got Its Curves, held at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, has been a highly anticipated event within the design community. After all, serious museum shows with significant catalogue on design are no longer easy to come by in New York.

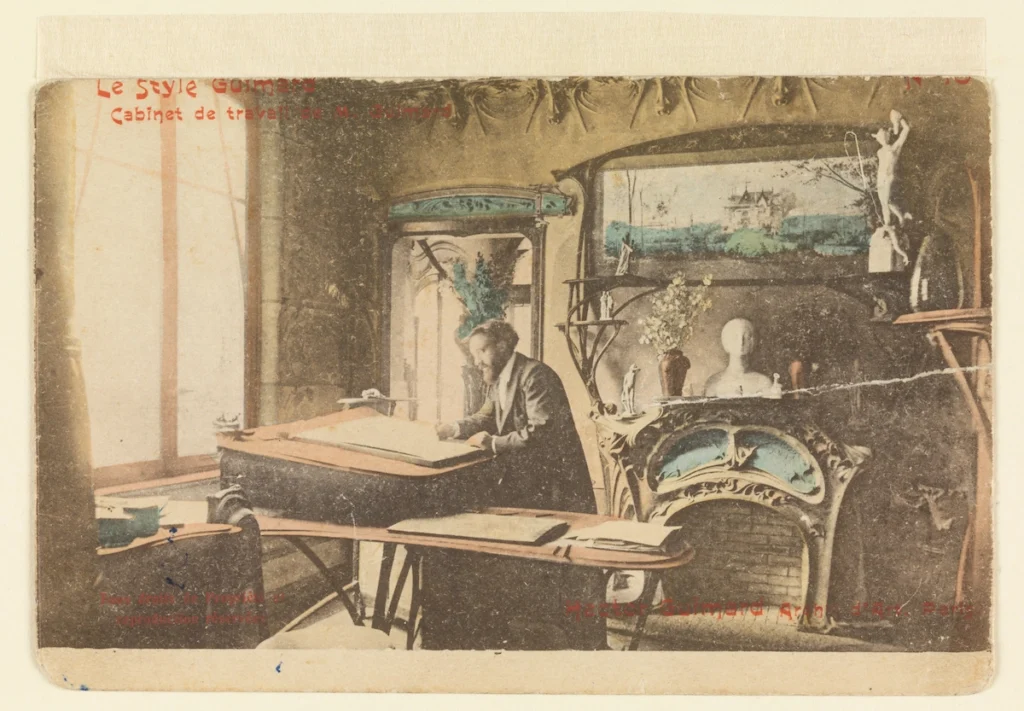

Elements of Guimard’s once-extensive work is still visible in occasion in Paris, even today, capturing his famed mantra ‘REject the flower, size the stem!’ Whether it is the remaining iconic entrance gates to the underground transport built for the inauguration of the Paris Exposition of 1900, which, with its beautiful patinated cast iron features, appear avant-garde even over a century later; or the Hôtel Guimard, the townhouse he built as his home and studio; or the earlier and over-the-top Castel Béranger, the residential building that still stands out in the 16th arrondissement; or the magnificent collection of furniture and objects on a permanent display at the Musée d’Orsay, his work has remained arresting and highly significant. He was so prolific during the first decades of his career that his style was not categorized simply as Art Nouveau, but instead called Le Style Guimard. He did it all: achieved the concept of a ‘total work of art’ like a few do, creating buildings, interiors, graphics, jewelry, and objects, integrated in spaces through his own personal language. Guimard has remained unmatched, but also enigma.

Displaying a wide array of objects, drawings, architectural elements, period films, and archival and personal material, this ambitious exhibition—co-organized by Cooper Hewitt and the Richard H. Driehaus Museum in Chicago—presents the multifaceted world of Guimard through his innovation and magnificent creativity. The last time New York saw a monographic show on the Art Nouveau figure was MoMA’s show of 1970.

The exhibition consists of objects from private and museums collections. The story of Guimard’s personal collection is rather interesting. A refuge from the Nazi- occupied France, he was living in New York when he died in 1942, and his widow was unable to convince the French authorities to acquire their home and its contents. In the 1940s Art Nouveau was not regarded as historically significant, and the French state had no interest in investing in what they considered insignificant material. MoMA’s Director Alfred Barr, who recognized Guimard’s greatness, was interested and acquired some pieces from Guimard’s own house for the collection.

It is not surprising that 50 years later the expectations for the exhibition at the Copper Hewitt were high, and I placed it at the top of my list of events to visit this fall. It is accompanied by a beautifully illustrated publication, Hector Guimard: Art Nouveau to Modernism by David A. Hanks, which includes interesting essays and new scholarship, particularly regarding hte architect’s modernist phase, seeking to recontextualize and reframe his oeuvre.

This show could be a glorious moment for the somewhat absent and forgotten Art Nouveau. It could have sparked widespread interest in the style, which has been largely excluded from design auctions and interiors in recent years. It could have been a new revival in fashion, furniture, objects, and contemporary design. I could see it in my imagination; but it was not, and it won’t be. If I could, I would ask the curators at the National Design Museum, why, for such an ambitious and important event that required a lot of effort and preparation, there was no attention or budget given to the exhibition design. I would ask why the show is so poorly lit, why the objects were placed in outdated glass cases, rather than creating an atmosphere that comes to evoke the spirit of the time. Architects—great architects—love designing museum exhibitions; they are waiting to be asked. I can think of at least three great New York architects who could have breathed life into this show, who could have turned it into a memorable experience, a blockbuster. I am saying this because this is a reoccurring issue at the National Design Museum when fantastic material, outstanding curatorial efforts, and newly presented scholarship are being overshadowed by the poor design; what a pity. Nevertheless, don’t miss this show, because it could be another half-century before Guimard will be celebrated again.