No other artist of the American Studio Movement has created furniture as expressive, dramatic, and sensual as California-based designer/maker Jack Rogers Hopkins (1920-2006). His sculptural pieces in stack lamination are so unusual and complex that it is hard to believe they were crafted in wood. Considering that Hopkins’ personal vocabulary is so easily recognized, there is little known about the artist who is not even featured in a Wikipedia entry and who was an outsider in the landscape of the Studio Movement. But now, with a new monograph, Jack Rogers Hopkins, California Design Maverick: Master Mid-Century Designer-Craftsman, his story has finally been told. The beautiful volume is a labor of love by design historian Jeffrey Head, who was the first to publish a monograph on Paul Evans, and who, together with Katie Nartonis, co-edited this important book, which sheds light not only on the evolution of Hopkins’ career, but also on his artistic process and the intellectual evolution of his concepts.

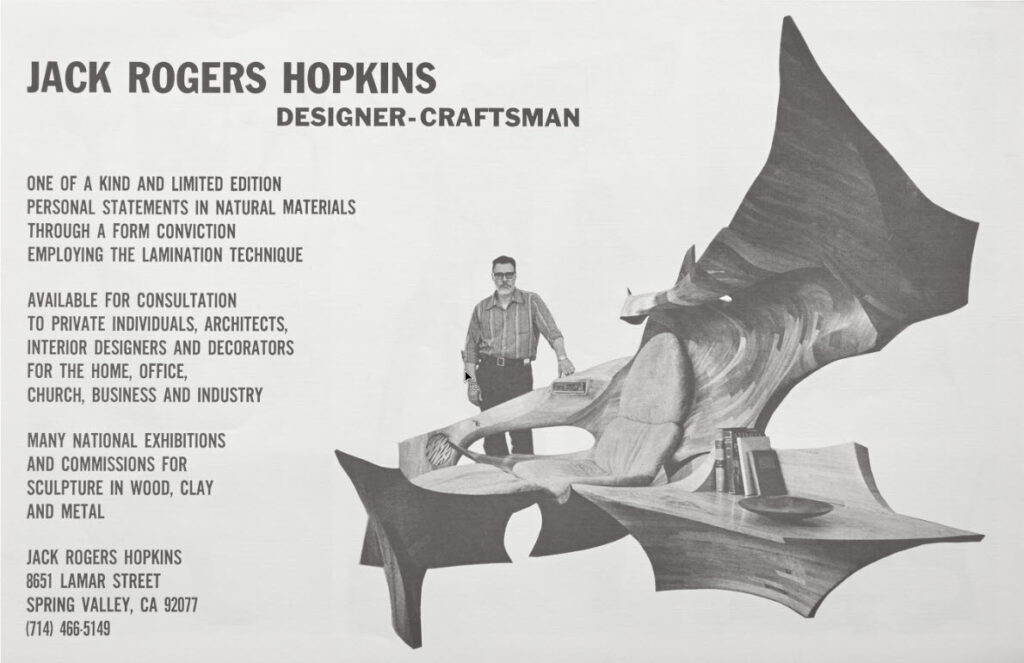

Since completing his first piece of furniture in 1966—a combined seat-coffee-table, crafted of Honduras mahogany in the stacked lamination method—Hopkins has defined his vocabulary, vision, and commitment to his craft. He was born to be a woodworker, trained in early childhood at his father’s furniture workshop, and noted in a local newspaper at the age of 12 for the sculptures he created from tin cans. Yet, it was not until he moved to San Diego to become a teacher at the Department of Art at San Diego State College, that Hopkins began experimenting with three-dimensional sculptural furniture. Throughout his career, he created several hundred pieces, much of which were commissioned by clients, professionals, and intellectuals who understood and loved his work, always without any assistance in the studio. Crafting furniture, he believed, was an artistic endeavor and therefore should be conducted solely by the artist. With the exception of his ‘Edition Chair,’—of which only seven were made—all pieces were crafted as one-of-a-kind, and each piece was signed with his full name.

I was surprised and disappointed to learn that Hopkins had never exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts, which was the premier platform to showcase the work of makers during the 70s and 80s. His work was unknown in New York, as he was known only locally. I loved reading the chapter written by his kids—a personal tribute to their father, who, they say, “provided an emotionally secure and loving environment which allowed us to lead normal, healthy, productive lives,” illuminating his role as head of the family and his daily commitment to his art—always testing new ideas, always working at the studio.

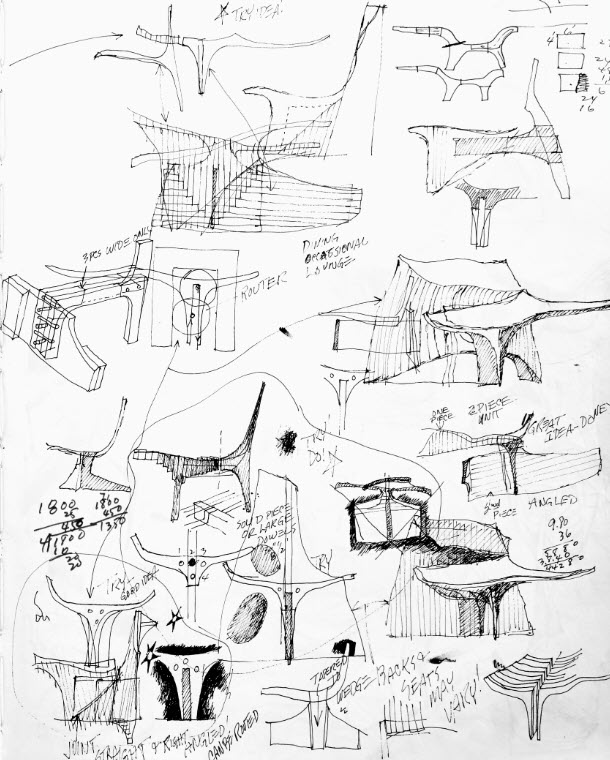

The wealth of drawings, sketches, and photographs reproduced in the book provides no hint of the tragedy yet to come. On July 6, 2018, twelve years after his death, the family home was completely destroyed by wildfire. The loss of the furniture, sculpture, personal jewelry, and artwork was the devastating conclusion to a remarkable career. Yet, miraculously, what was rescued from the ashes are the notebooks, photographs, and ephemera—materials which have made this book possible. It was published in a small edition of 150.

Above: Jack Rogers Hopkins, Sculpted Chair and Table, ca. 1975; courtesy Wright.

California Design Maverick:

Master mid-century designer-craftsman

Edited by Jeffrey Head & Katie Nartonis