If you have never heard of Robert Pfannebecker, it is because the subject of his collection—studio objects in clay, fiber, glass, and metal—has been marginalized and excluded from the art market and museum collections for decades. He is a collector-patron of a kind that is rapidly disappearing from the world; a true collector-turned-connoisseur who is celebrating his 90th birthday this year. Pfannebecker is a corporate attorney who began his journey into the world of collecting in the mid-1960s, and has assembled one of the finest collections of its kind, with objects that signified new and radical directions in design, created by independent craftsmen who heralded these objects as works of art.

Now a small portion of Pfannebecker’s collection is exhibited at R & Company, consisting of works of excellence, of museuem qulity by some of the leading figures in the Studio Movement such as Fred Bauer, Helen Bitar, Dale Chihuly, Jun Kaneko, Marvin Lipofsky, Richard Marquis, Eleanor Moty, Ron Nagle, Betty Woodman, Don Wright, and more. It is clear that through decades of engagement he has demonstrated the power of collecting to develop an educated taste and an eye to recognize the radical, the expressive, the unique. His collection further demonstrates that collecting does not require deep pockets, but passion and commitment.

Born in 1933 in the farm country of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where he still resides, Pfannebecker famously traveled the country in his station wagon—visiting schools and meeting teachers and students, all while acquiring works and forging patronage and friendships. When visiting RISD, he met Dale Chihuly and his student James Carpenter when the two created experimental sculptures in glass, and at Berkeley he met studio glass artists Richard Marquis and Marvin Lipofsky. He visited the schools with the best art and design departments, beginning decades-long friendships built on dedication to support and patronage of glass artists, studio ceramicists, and fiber artists. By the 1980s his immense collection of contemporary craft consisted of thousands and thousands of objects, all installed at his home.

When he was interviewed by Helen Drutt for the Oral History project of the Smithsonian in 1999, Pfannebecker revealed that his interest in crafts and collecting was driven by his associations with students and teachers at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in the 1960s. In his personal statement for the exhibition catalog he states, “I have been extremely fortunate to have developed lasting relationships with several artists who have become longtime friends. The acquisition of their work has been ‘my alternate reality.’”

Today, as crafts are slowly penetrating into the art market and many fine artists are using clay and fiber to express their contemporary ideas and political stands, the collection of Pfannebecker could not be more relevant. Some of the pieces in the show are breathtaking, evoking the various art movements of the time to which these craftspeople were related. I loved the sections devoted to Betty Woodman and to Dale Chihuly’s early work, as well as the beautiful showcase of tiny, perfect cups in glass and clay. Each one is different, and each is a jewel. It is hard to believe that these works were considered inferior at the time of their creation. The exhibition was co-curated by Evan Snyderman and James Zemaitis, who led a tour of the show. The two have made many trips to Pfannebecker’s shingle A-Frame house, selecting those pieces out of southands and seeking the adventurous objects which signify the expressive use of materials and ideas. The exhibition will be on view through April.

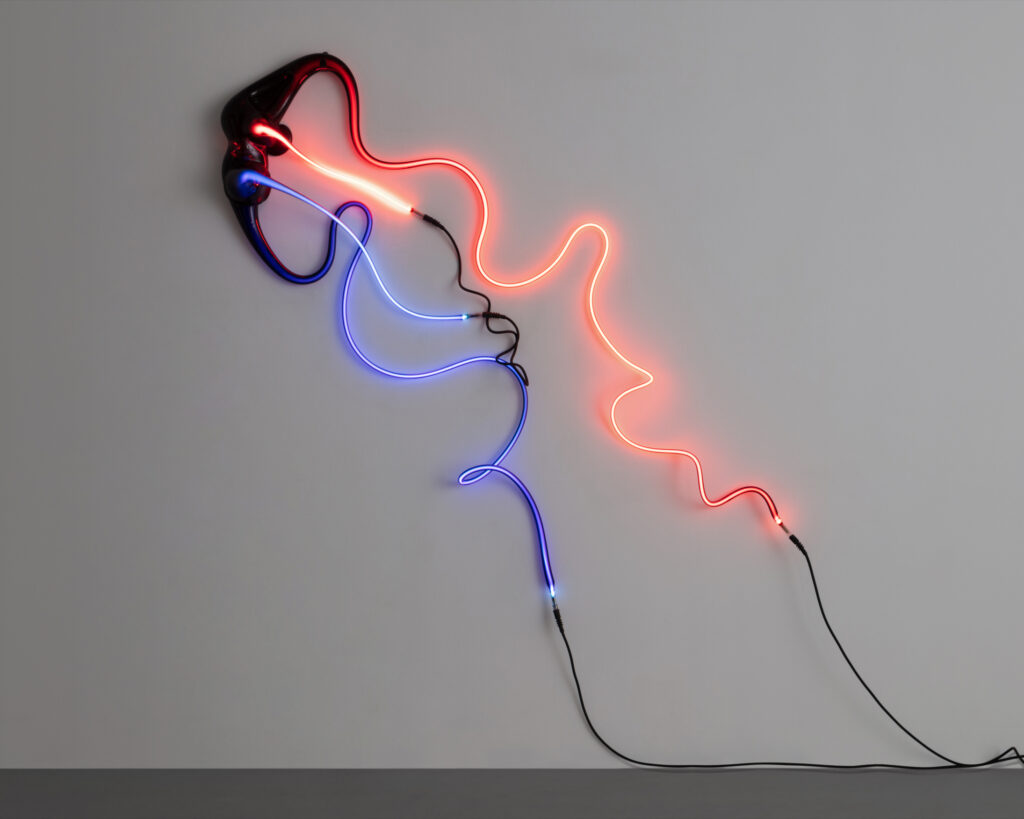

Illuminated wall sculpture in red and blue hand-blown

neon glass. Designed and made by Dale Chihuly and

James Carpenter, USA, c 1976.