Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Remembrance Center built on the slopes of Mount Herzl in Jerusalem, is the most poignant building I have ever visited. A good building will make you feel, but Yad Vashem will make you cry; it connects with the inner part of your soul. I was interested to see this building not only because I am a daughter of a holocaust survivor and grew up surrounded by people with Auschwitz tattoos, but also because unlike other Holocaust museums (i.e., the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC) Yad Vashem brings you straight into the world of those who directly experienced that tragedy. Its power comes from the architecture itself; when you walk through this long triangular building, you can fully understand what it means to emerge from dark to light, “sharpened and amplified the narrative” without competing with it, says its architect Moshe Safdie in his newly published memoire If Walls Could Speak (published by Grove Atlantic). To me it was a memorable, nearly physical experience to see my grandmother’s dark days in Nazi-occupied Budapest; the harsh journey to freedom, and the bright future of Israel manifested as an enormous skylight at the end of the building, which I was able to connect with. When Safdie took Senator Barak Obama through Yad Vashem, it was probably the best lesson the future President could have received on the Zionist project and the fate of the Jewish people.

Sitting at his home in Cambridge, MA during lockdown, Safdie decided to focus on the project that he had started years ago: a memoir to tell the story about the eight decades of his magnificent life and an extraordinary six decade career at the forefront of the world of architecture, which intersected with events that came to shape history as we know it. To name a few, he had a friendship with Yitzhak Rabin and designed an unusual tombstone in black and white after he was assassinated, during one of the most tumultuous moments in Israel’s national life; he had a relationship with Alice Walton, the world’s richest woman, whom he called his “most astute and collegial client” when designing her Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas—a special museum for the community on a level never seen in this part of the country; he held a private concert by Yo-Yo Ma and Daniel Barenboim in the living room of his 18th century house in Cambridge; and he crossed the Allenby Bridge from Israel to Jordan the day after signing the peace treaty between the two, making him the first Israeli to visit the archaeological city, which up until then was set in the Israeli conscious as a place of danger from which no young adventurers return alive.

Safdie was born in Israel and moved with his family to Montreal at age 15, making Canada’s province of Québec his home until much later in life when, as an architect, he moved his office and residency to Boston. Growing up in Haifa and studying at the all-Ashkenazi Hebrew Reali School was unusual for a Sefardi boy in pre-state Isarel of the 1940s, but he did know at the time that his parents had to take advantage of special connections in order to get their son admitted into the prestigious school. But his life in British Mandate Haifa had a great effect on his architectural thinking. The modernist neighborhood of Hadar HaCarmel, where the young family lived, filled with white apartment houses and designed according to the principles of the European Modern Movement left an imprint on his visual memory. This was also when he began to develop his own dream of the ideal home—one with a garden or outdoor space and a view of nature. But this dream had an abrupt ending. His father, a textile merchant, was suffering from the strict rules and restricted import set by the new socialist government after the State of Israel was founded, and he had no choice but to immigrate.

Having to leave the familiar behind and immigrate to Canada with his parents had an effect on Safdie’s identity, as immigrants have shown a pattern in achievement and ambition. Once he entered McGill School of Architecture, he found his passion. From then on, his life and career turned into a series of successes. At McGill he was named University Scholar, and two years after graduation, started his career at the Philadelphia office of Louis Kahn—America’s greatest architect of the 60s. There, he was able to witness the genius at work; to learn the ‘craft’ of architecture, in his words, and even to personally design the gutters in Kahn’s Salk Institute. A year later, he was invited to submit a proposal for a housing project for the upcoming World Exposition of 1967. It is hard to believe that his first project, or any architect’s first project for that matter, became so iconic, which was a point of departure for a magnificent, global career. He was then responsible for rebuilding and transforming the City of Jerusalem in the decades following the Six-Day War: building museums, civic projects, cultural and educational institutions across the globe, and making his contribution to the built fabric of the world, and the academic appointment of the Director of the Urban Design Program at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design (GSD).

Habitat 67 was the entry ticket to the pantheon of the world of architecture. Its concept was born from the memory of modernist Haifa, but also from what he learned from traveling across the United States on a scholarship as an architecture student at McGill, visiting many housing projects along the way. He knew that the monotonous brick housing with small windows—even the more luxurious examples designed by Mies in Detroit, for example—have to be revisited. Habitat was not suburban or urban, not high rise or single house, but something in between. I would like to think of Habitat as the modern version of the Garden City Movement of the early years of the 20th century, which promoted satellite communities surrounding the central city and separated by greenbelts. However, Habitat is an urban project, inserted in the city and transforming the quality of life for the residents. It was Safdie’s innovative and bold concept for urban living and he was in his 20s. When he expanded it 50 years later in Habitat Qinhuangdao in China, as a high-density housing in a garden atmosphere, the concept was finally fully realized.

In my recent series Architecture: The Legends, we learned that architects today do not necessarily have to have a signature style; instead they have to have signature conceptions, views, and visions. To Safdie it is, in his words, “unleashing the power of the place.” It is about letting the landscape not only speak, but also determine the architecture. He learned this from the ancients, from Petra, which was carved in the red stone; from Machu Picchu, the 15th century Inca citadel where the Incas discovered the wonder of nature. Unlike Mies—whose work he challenged as a student and who could create identical designs for South America and Europe while celebrating architecture as an international entity — Safdie always been on a quest for the site specific, and will be remembered for his respect for the natural setting. If Walls Could Speak is a fascinating account of a great architect and a great man. Highly recommended.

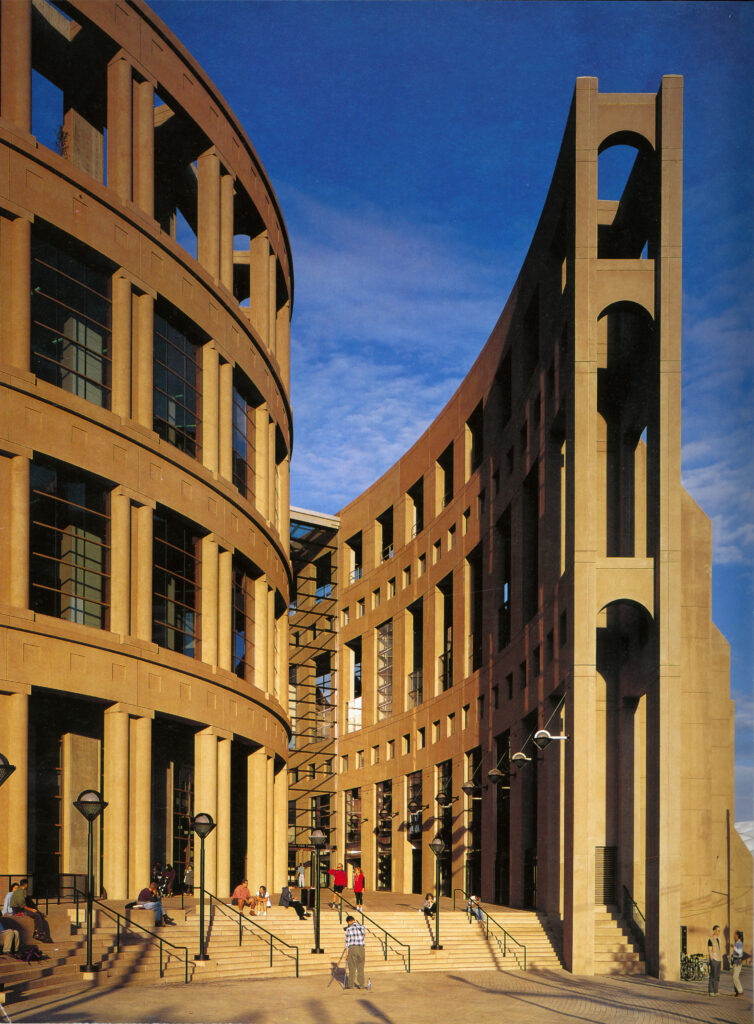

Great review of an amazing architect. (One small note, photo of Crystal Bridges needs correct identification).

Wonderful article. Will definitely get his book!