Few would disagree with the statement that Louis Kahn (1901-1973) was the most important architect of the third quarter of the 20th century. While he did not create a lot because of the misfortune of living and building an architectural career during the Great Depression, yet, every building that the Philadelphia-based architect completed – Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, the library of Phillips Exeter Academy in Exeter — has been a spiritual gem and milestone in the story of modern architecture. This is why, when the news came out this week that the dormitories of his iconic Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad (IIMA), which Kahn completed in 1974 in Ahmedabad, India, considered to be one of his most prominent works, are set to be demolished, many unhappy voices appeared in the architecture press.

The board of the IIMA has announced that at least 14 of the 18 dormitories will be demolished and replaced with new buildings. The reason being ‘problems of leakages from the roof, dampness in walls, leakages in toilet walls, slabs, etc,’ not untypical to postwar construction. The new dorms would increase the capacity of the campus from 500 to 800 – again, typical to postwar buildings which tended to be smaller in size and scale, making them hard to fulfill functions of today’s needs. But this a masterpiece, Louis Kahn’s legacy.

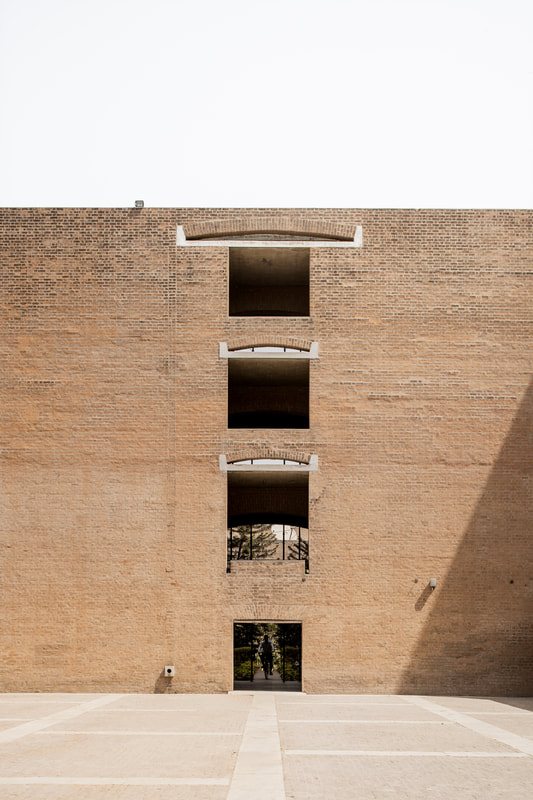

His vision was always unique and personal. When everyone else sought to create futurism and used glass and steel, Kahn passionately sought to connect with the traditions of the ancients, the Egyptians, the Greeks, the Romans, and to use poor materials; when everyone looked to achieve the ideal perfection of modernism, he fell in love with the imperfection of William Morris and admired his Art of Building. Kahn’s signature style as appeared in the IIMA –merging of modernism with classical sensibilities, the timeless silence of architecture volumes, and the use of red brick — all derived from ancient Roman baths.

The board of the IIMA has announced that at least 14 of the 18 dormitories will be demolished and replaced with new buildings. The reason being ‘problems of leakages from the roof, dampness in walls, leakages in toilet walls, slabs, etc,’ not untypical to postwar construction. The new dorms would increase the capacity of the campus from 500 to 800 – again, typical to postwar buildings which tended to be smaller in size and scale, making them hard to fulfill functions of today’s needs. But this a masterpiece, Louis Kahn’s legacy.

His vision was always unique and personal. When everyone else sought to create futurism and used glass and steel, Kahn passionately sought to connect with the traditions of the ancients, the Egyptians, the Greeks, the Romans, and to use poor materials; when everyone looked to achieve the ideal perfection of modernism, he fell in love with the imperfection of William Morris and admired his Art of Building. Kahn’s signature style as appeared in the IIMA –merging of modernism with classical sensibilities, the timeless silence of architecture volumes, and the use of red brick — all derived from ancient Roman baths.

I know that Kahn’s architecture is hard to fully comprehend without a physical presence that makes his oeuvre and emotional contents easy to ‘feel.’ After all, it happened to me when visiting the Kimbell Art Museum, his masterpiece in Fort Worth, Texas, where the barrel-vaulted galleries and long courtyards, the dramatic vaulted ceiling, lit naturally allowed me to experience art like nowhere else. I have never visited the IIMA in India, yet, I can say by looking at photography of the buildings set to be demolished, that losing Kahn’s heritage is going to be as tragic as his own life, which was captured by his son Nathaniel Kahn’s memorable documentary My Architect: A Son’s Journey of 2003.

All photographs: Jeroen Verrecht.

Sign petition.