I clearly remember the day I fell in love with Japanese crafts. It was when I met George Nakashima at his studio in New Hope, Pennsylvania for the first time. It was the hottest day in that summer of 1987, and he was sitting in the showroom, surrounded by pieces of furniture crafted in wood. You can read all the books you want; you can attend designer showcases, lectures, exhibitions. But when you went to Nakashima studio, you understood Japanese design. Growing up in Israel in the 70s, we lived in direct contrast to the pristine beauty, the calmness, the sense of perfection that I experienced in New Hope. But I realized that this perfection so precisely complements my own personality. Ever since, I have developed love and deep appreciation of Japanese handcraftsmanship, and in my travels to Japan, I always love visiting the studios of Japan’s craftspeople. Those trips have strengthened the understanding of and the ability to evaluate Japanese crafts.

I was therefore thrilled when a new publication landed on my desk: Handmade in Japan: The Pursuit of Perfection in Transitional Crafts, by Irwin Wong (published by Gestalten). With an introduction by Kengo Kuma, the Japanese architect who is credited with rediscovering traditional Japanese crafts and for incorporating them into his remarkable architecture, the book was promising from the minute I opened it to the first page. “There are strong regional differences regarding the natural materials used by Japanese craftspeople,” Kuma says. This encyclopedic volume comes to follow that diversity by exploring Japan’s various regions and its people’s crafts.

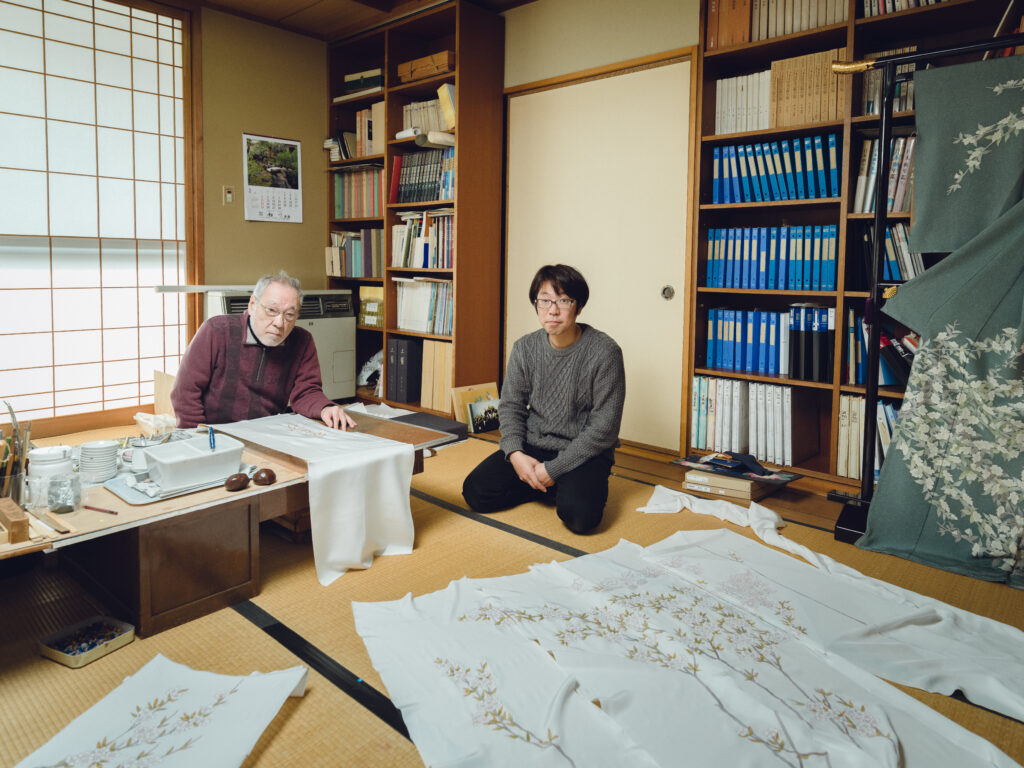

Wong, a photographer who has explored Japan when writing this book told me that this is his ultimate labor of passion and love. He moved to Japan in 2005 and his fascination with crafted musical instruments by Stradivarius has brought him to fall in love with the world of centuries old Japanese crafts and in this book, sought to get a cross section of the landscape of current Japanese traditional crafts. While there is a great moment for Japanese kogei, he was not looking to focus on high-end, or on those successful artists with global careers. He rather looked for workshops where craftspeople toil on day by day, with a special interested in those craftspeople who create contemporary products by utilizing traditional techniques and prevent them from being extinct. Don’t look for the names you see in museum collections or galleries. Here, we meet unknown and fascinating artisans. Shuji Nakagawa, a member of the Kyoto-based collective Go-On, for example, has created a new paradigm for wooden buckets (ki-oke), by crafting such contemporary items as champagne buckets.

The future of Japanese kogei is worrying, and Wong is not excluded. “My concern is that the ‘middleclass’ of Japanese crafts will slowly wither and only the extremely successful high-end artisans will remain”, he said to me. “This will be unsustainable in the long term, as there will be a need for craftspeople to provide materials and tools, and if that ecosystem collapses, it will spell bad news for the industry as a whole.” On the other hand, he is hopeful. “Through my research and interviews for this book,” Wong reveals, “I have come across a great many individuals and organizations that work tirelessly to sustain and promote regional crafts, and I believe the Japanese people are very aware that maintaining this priceless cultural heritage is very important.”

This is one of my favourite books. I just returned from Homo Faber in Venice where 12 National Living Treasures were sharing their work – it’s extraordinary to be in the presence of such greatness.