During her lifetime (1878-1976), Eileen Gray was hardly known in her homeland of Ireland. It is astonishing that the self-taught designer/architect was unknown, considering she worked during the height of the French avant-garde and cemented herself as one of the most innovative and interesting talents working in Paris. Gray collaborated with some of the world’s most iconic art patrons creating furniture, lights, and some of the best interiors of the century. Yes, except for one small exhibition of her rugs that was held at the Bank of Ireland when she was 95-years-old, she has no presence in Ireland. Ireland was not along. Following WWII Gray was went to obscurity, and her unique contributions to design went largely ignored and excluded from the historical narrative of modern design. Now Ireland recognizes the woman who succeeded in a time that suffered from an absence of women working in design by holding the world’s most comprehensive and celebrated collection of her work at the National Museum of Ireland, cared and curated by Dr. Jennifer Goff, Curator of Furniture, Silver and the Eileen Gray Collection. I had the privilege of being her guest this week.

Gray was born into an aristocratic family and studied drawing and painting growing up. She fell in love with Japanese lacquer, which she discovered in the collection of the V&A in London, a discovery that came to shape her life and career. She moved to Paris at age 24 and immediately began designing screens and panels covered with beautiful, silky, colorful surfaces of lacquer—a technique which she learned from Japanese lacquer master Seizo Sugawara. It was her personal merging of modern art with Japanese traditional handcraftsmanship which had brought her into the center of the Parisian avant-garde during the 1910s and 1920s. The transition from the handcrafted luxurious objects to modernism and cutting-edge architecture with machine-aesthetics was seamless. After WWII, design and art moved in new directions, and the a new generation emerged while Gray being left behind and forgotten. She lived in isolation until she was rediscovered in one article, published in Architectural Review when she was at the old age of 94. In the late years of her life, she worked with London-based furniture merchant Zeev Aram of Aram Furniture in London to reproduce her furniture designs until she died at 98-years-old.

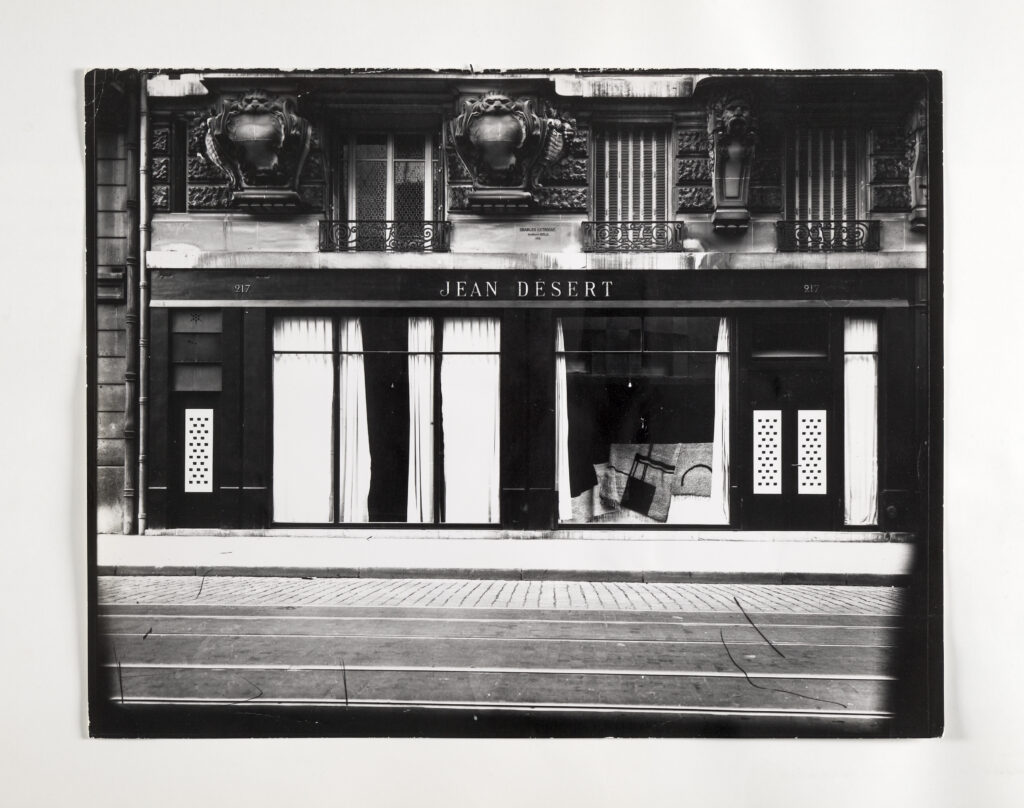

The fantastic collection at the National Museum of Ireland includes not only some exquisite examples of furniture—such as the prototype of her famed “Adjustable Table”—but also family photographs, lacquering tools, books, and other personal ephemera. In Goff’s hands, awareness of Gray’s immense talent has been fully revived, and she can be credited for the critical attention that her work has received in recent years. Goff believes that Eileen Gray was Irish first and foremost, and that there is no better home for her collection to explore and exhibit her legacy than at the National Museum of Ireland. Gray said she never forgot her homeland, and after the exhibition in 1973, she expressed a desire to produce rugs in Ireland. Goff’s 2015 monograph, Eileen Gray: Her Work and Her Life is considered the most important document on the designer, tracing the evolution of her work from Art Deco to Modernism, the venture of opening her Parisian retail shop Jean Désert, her relationship with Le Corbusier, and with her mentor and lover architectural critic Jean Badovici. Goff curated a monographic show at the museum and a member of the curatorial teams of the subsequent shows at the Centre Pompidou (2013) and at the Brad Graduate Center (2020). Her devotion to preserve the legacy of Eileen Gray is unparalleled.

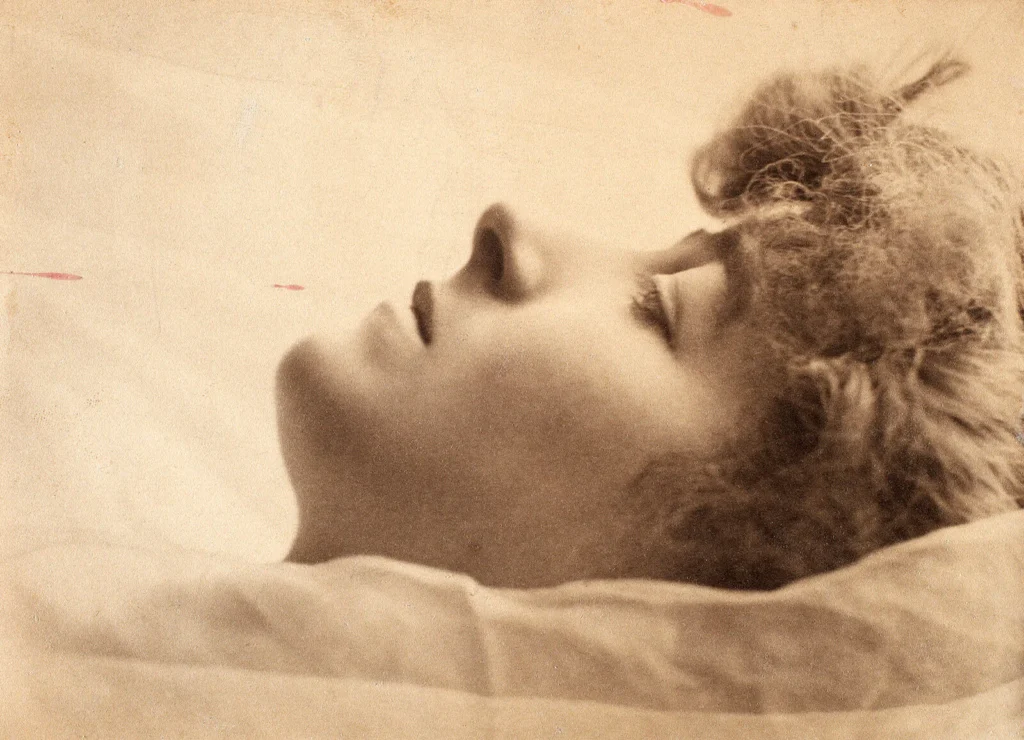

Goff guided us through the entire collection, which consists of a permanent exhibition and an archive. Most of the collection at the National Museum Ireland came from the home of British author and executive producer with BBC, Peter Adam (1929-2019). He was the man who brought Gray to life with his book Eileen Gray: Architect/Designer, the first full-scale biography that was published in 1987 and has since become classic in design history. Adam was a close friend of British artist Prunella Clough (1919-1999): the niece of Eileen Gray who inherited her estate and gifted it in its entirely to Adam, who later sold it in three segments to the Museum. In the archives, we saw letters, photos, books, and drawings that brought Gray to life. Thank you, Jennifer Goff for opening this collection to us and for making this visit a memorable one. Images: © National Museum of Ireland.

Eileen Gray exhibition galleries at the National Museum of Ireland – Decorative Arts & History, Collins Barracks, Dublin 7 © National Museum of Ireland

Eileen Gray exhibition galleries at the National Museum of Ireland – Decorative Arts & History, Collins Barracks, Dublin 7 © National Museum of Ireland

Eileen Gray exhibition galleries at the National Museum of Ireland – Decorative Arts & History, Collins Barracks, Dublin 7 © National Museum of IrelandEileen Gray exhibition galleries at the National Museum of Ireland – Decorative Arts & History, Collins Barracks, Dublin 7 © National Museum of Ireland.

Eileen Gray exhibition galleries at the National Museum of Ireland – Decorative Arts & History, Collins Barracks, Dublin 7 © National Museum of IrelandEileen Gray exhibition galleries at the National Museum of Ireland – Decorative Arts & History, Collins Barracks, Dublin 7 © National Museum of Ireland.