No other furniture designer has become as well known—as much a household name—as Thomas Chippendale. He was so prolific in the 18th century that his name has become synonymous with a particular style. But Chippendale is not a style, and is certainly not the heavy mahogany furniture associated with the name. Thomas Chippendale was a London cabinetmaker whose manual had come to shape the course of history. A new handbook recently published by Shire sheds light on the man and his legacy.

The style has gone in and out of fashion since it was devised in the 18th century, and right now we are in a moment when Chippendale and his ornate, rococo-like, gothic-like vocabulary is excluded from contemporary taste. I asked co-author Adam Bowett about the relevance of Chippendale today. Bowett, who authored the book with James Lomax, is a furniture historian and is also the Chairman of the Chippendale Society. “Chippendale,” he said, “is relevant in the same way as any historic artist is relevant – or not, depending on your point of view. My view is that all art, including applied art and material culture, informs the art that comes after it. We understand where we are now by understanding where we have come from, and if we lose sight of that we risk losing our perspective on the world.”

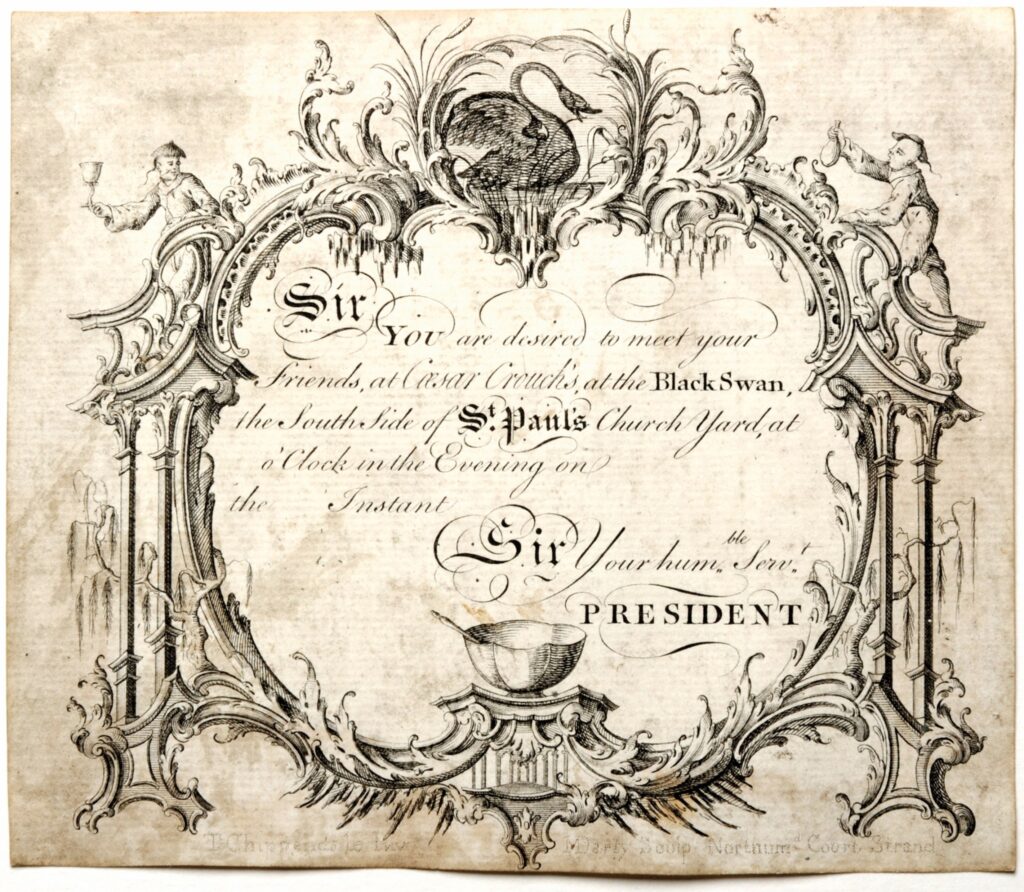

While Chippendale was a gifted businessman and a genius in branding, he never really invented a style, but rather mastered an emulation of existing styles that were in vogue during his time. His most substantial contribution to the story of design was his blockbuster book, The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director, which consists of hundreds of drawings, and was used by carpenters and craftsmen in England, France, and America during the 18th century and after. “Chippendale,” Bowett told me, “was the first furniture maker to fully recognize and use the power of print to disseminate his ideas – print being the Internet of the pre-electronic age. Through the Director, Chippendale acquired a national and international reputation and ensured that his name later became identified with an entire style of art and design.”

My favorite chapter in this book is entitled Legacy. Here, we learn how Chippendale and his book came to impact designers for future generations. The 19th century witnessed a tremendous revival, along with other historicist revivals. Then came the 20th century, and in its first half, when the world was fascinated with the Modern Movement, and Chippendale was excluded from the cutting-edge design, was nevertheless popular in American and English homes. However, once this came to an end, Chippendale was rediscovered. The most famous example is Roberto Venturi’s Chippendale Chairs, which he created for Knoll in the late 1970s, and the enormous arch, topping the AT&T building, Philip Johnson’s masterpiece of postmodernism, completed in New York in 1981. What I miss is seeing more of this. I am curious to learn how Chippendale is influential today — or perhaps is not. Whether contemporary architects and designers today pay tribute to history’s most famous furniture designers, and if not, why don’t they?

Images of historical work courtesy Chippendale Society.