Why are British studio ceramics significant? What about them has captured the imagination of art lovers and collectors across the globe? It is certainly different than the clay art made in Japan, Korea, America, Africa, South America, or France, and its story is fascinating; one of a century-old movement that has achieved great heights. The innovation of British ceramics in the 18th century has been extensively studied and documented—a time when the Industrial Revolution stimulated entrepreneurs such as Josiah Wedgwood and those who founded the earliest porcelain factories on the British Isle like Crown Derby, Worcester, and Chelsea Porcelain. But when it comes to the studio ceramics movement, many of its participants have remained unknown and its story has yet to be uncovered.

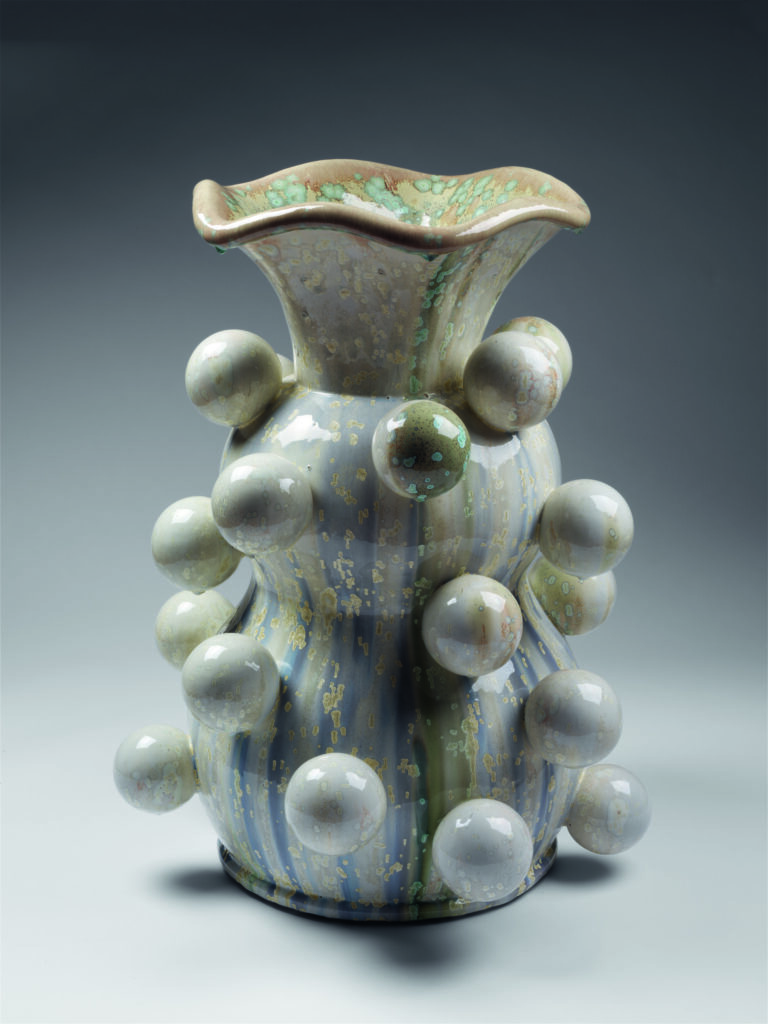

The movement emerged after the First World War, reaching its peak in the 60s and 70s with some exquisite and innovative techniques, materials, and presentations. British studio ceramics are among the most desired in the market of design and decorative arts, collected by both museums and private collectors alike. Now a new encyclopedic volume titled Studio Ceramics by Alun Graves (Senior Curator of Ceramics and Glass for 1900-now in the Department of Decorative Art and Sculpture at the Victoria and Albert Museum) has comes to fill the void. With the work of Lucie Rie and Hans Coper fetching six figures in the marketplace, British ceramics moving from the typologies of the vessel to a form of art installation, and artists such as Rachel Kneebone, Grayson Perry, and Edmund de Waal using clay as a material in contemporary art—this new publication is an incredible celebration of the studio ceramic movement while also serving as the catalogue of the museum’s collection, based on a 1990 pioneered publication by Oliver Watson. It provides an educational tool through examination of the museum’s extensive collection.

The book is divided into two main sections following an introductory essay in which Graves provides historical context and summarizes the story of British studio ceramics. The first part is a chronological catalog of the collection, illustrating the evolution of British studio ceramics from the first decade of the 20th century to the recent works crafted up to 2019; this is the most part of the book as it presents the wide breadth of materials, styles, and techniques that were employed by British ceramicists throughout an entire century. The second part is devoted to the artists, containing an extensive encyclopedic list including all of the artists included in the collection. This beautiful volume is a mandatory addition to any library of design, decorative arts, and collecting. It is a true celebration for lovers of ceramics.