“The simplicity of the architecture and the scale and proportion of the rooms bring a much needed sense of calm and order to the hustle and bustle of urban life. The enormous square-format windows frame the views of New York and beyond in a way that feels appropriately epic, romantic, and grand, allowing the viewer to take in the landscape in a powerfully memorable way. You are left with a sense of awe at it all, an awe that somehow never dims with time.”

—Interior designer Kelly Behun on Rafael Viñoly’s 432 Park Avenue

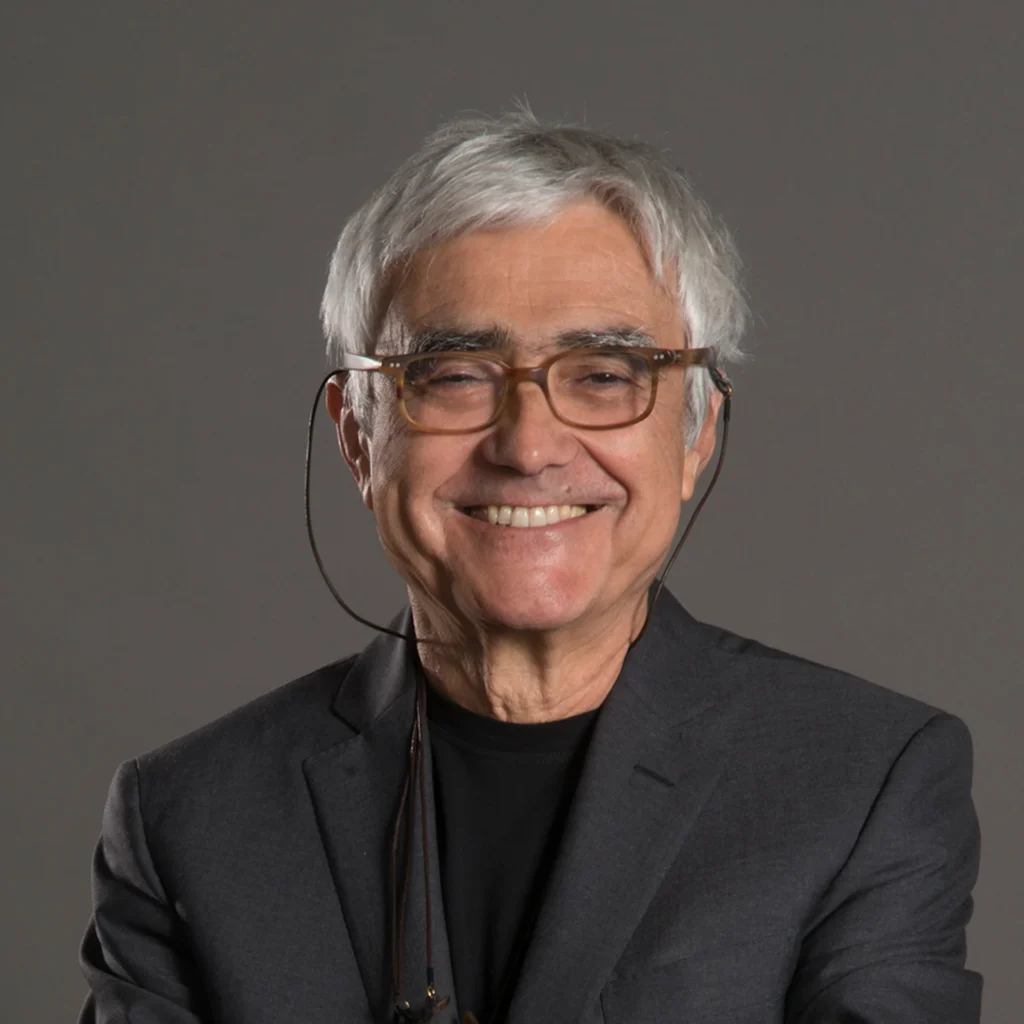

Rafael Viñoly’s central quest is architecture of joy. His role, as he articulated during last week’s Architecture: The Legends program, is not to create building-sized sculptures intended merely to be seen, but rather places that people enjoy using. He was thrilled when I read him the glowing words (cited above) that interior designer Kelly Behun had for his 432 Park Avenue tower, where she lives on the top floor. Adding to the praise, I told him that New York never looked better than the clear autumn night I visited Behun and took in the view through those perfectly square windows. Warmly smiling, he revealed his nature to be humble, patient, and gentle—quite unexpected from such a prominent architect whose impact on the built environment spans six continents. Our conversation over the next hour was open and authentic, allowing the audience and me to glimpse the genial man behind the immense architectural achievements.

Born in Uruguay and raised in Argentina, Viñoly seemed destined to become a professional pianist before changing course in his late teens to study architecture at the University of Buenos Aires. There he earned a Diploma in Architecture in 1968 and a Master of Architecture degree in 1969. Music, however, never left him. Decades later, his architecture would shape countless music lovers’ experiences through The Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts in Philadelphia, the Jazz at Lincoln Center Hall in New York, and the Curve Theatre in Leicester. This year saw the release of the Maene-Viñoly Concert Grand, an innovative, ergonomic piano developed over six years by Viñoly and master piano maker Chris Maene with the aid of biomechanical and acoustical computer modeling. Seeing humans standing at the center of both architecture and music, Viñoly designed the keyboard’s curve to match the natural sweep of the pianist’s arms.

On the relationship between music and architecture, Viñoly recalled German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s famed line, “Music is liquid architecture; architecture is frozen music,” a sentiment with which he disagrees. The experience of music, Viñoly told us, is different from the experience of architecture; the former is abstract, the latter material. As he remains a music connoisseur and a regular at the New York Philharmonic, the Metropolitan Opera, and Carnegie Hall, Viñoly likes to oscillate between the two realms.

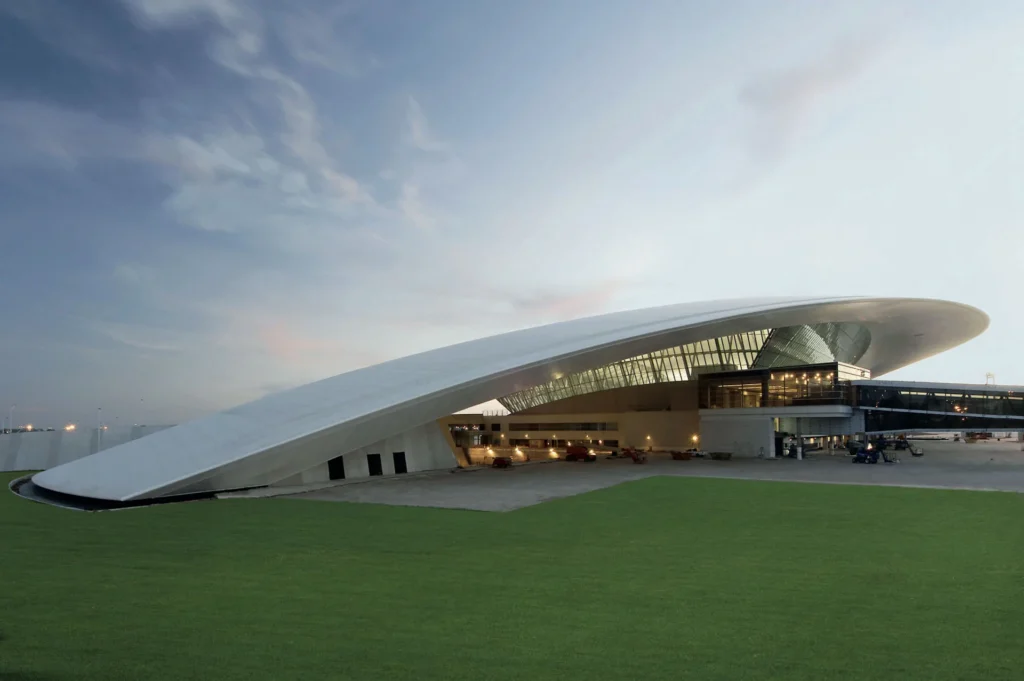

Viñoly is a true modernist, carrying forward the 20th-century movement’s aesthetic predilections and humanistic aspirations into the 21st century. His work brings out the timelessness of glass, steel, and concrete rendered in grid-like compositions, abstract forms, and industrial finishes—modernist materials stretched, adapted, and upgraded for today’s technological and social context.

In our conversation, he extolled Brazilian modernist Oscar Niemeyer for the role his singular creations played in the advancement of the field of architecture. He also expressed admiration for German modernist Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, particularly Mies’ sober language, informed by classical training, that transformed the modern urban landscape along with the public’s attitude toward architecture. Viñoly said his favorite New York skyscraper is Mies’s Seagram Building, and he called Mies’ Edith Farnsworth House “a genius masterpiece.”

Parallels run between the life stories of Viñoly and Mies, who was a rising architecture star in Weimar, Germany, until the Nazis took power. When it became clear that the architecture of the Third Reich would embrace a heavy-handed revival of traditionalism while rejecting the sleek, intellectually-driven modernist style, Mies made the decision to emigrate to Chicago. In the US, he accepted a teaching position before building his practice anew. Soon enough, Mies found success in the US, even greater than he had in Germany.

Four decades later, Viñoly traversed a similar path: He fled his home, leaving behind a flourishing architecture practice, to escape the brutal junta dictatorship in Argentina. Seeking refuge in the US, he also taught before reviving his practice. Like Mies, who would go back to Berlin years later to construct the Neue Nationalgalerie, Viñoly has since built a number of ambitious public projects in Argentina, including the Colección de Arte Amalia Lacroze de Fortabat Museum and the University of Buenos Aires Faculty for Mathematics, Computer Sciences, and Environmental Sciences.

Through Estudio de Arquitectura, the firm he co-founded in Buenos Aires at the start of his career, Viñoly designed Mendoza Stadium, where Argentina’s national team would go on to win the 1978 FIFA World Cup, the country’s first-ever Jules Rimet Trophy. This moment of national triumph, however, was coopted by the murderous military government that overthrew the democratic order two years earlier, framing the win as justification for its corrupt power. Coincidentally, a Uruguayan magazine had just reprinted the 1933 correspondence between Bruno Walter, Berlin Philharmonic conductor, and Alma Mahler, his mentor’s widow, in which she urged Walter to leave Hitler’s Germany to save himself. Sitting in his stadium watching the historic victory, Viñoly knew that he had to leave Argentina immediately, before it was too late.

Viñoly explained that being an immigrant—both from Uruguay to Argentina as a child and from Argentina to the US as a young man—has profoundly shaped his identity, instilling in him an aptitude for uncovering alternative solutions and adapting to changing realities. He also credited his father, renowned Argentinian film director Roman Viñoly, “a dreamer,” in Viñoly’s words, for teaching him to trust his abilities and ambitions.

In 1983, Viñoly established Rafael Viñoly Architects in New York City, and his first serious project was the renovation of the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. It was “an exercise,” as he called it, in harnessing the power of architecture to improve people’s lives while also working within very tight budgets. This public college, part of the City University of New York system on Manhattan’s West Side, was housed in a former high school built in 1903 and needed to expand. Carefully preserving the historic, Flemish Baroque facade, Viñoly added a skylit atrium to improve interior circulation as well as other contextually sensitive additions to meet the client’s programmatic plans.

Thirty years later, Viñoly transformed Manhattan’s skyline with a slender, soaring tower—the highest residential tower in the Western World and the second tallest building in New York after One World Trade Center. Featuring four identical facades and a distinct geometrical monumentality, 432 Park Avenue shoots straight up, visible from all five boroughs. Constructed within the small footprint of the old Drake Hotel, Viñoly’s design, a masterpiece of engineering, sparked a new generation of luxury apartments in NYC. The so-called “Billionaires’ Row” of skinny residential skyscrapers was also fueled by new zoning laws that permit developers to buy the air rights of adjacent properties. Among the seven towers currently in the row, 432 Park Avenue remains the most iconic, thanks to its elegant silhouette that so perfectly encapsulates Viñoly’s lofty principles.

To Kelly Behun, 432 (as it became to be known) is an exemplar of architectural thinking, offering a serene oasis with magnificent views that frame the magical city’s four seasons like photographs. To me, an admirer of extraordinary minimalist architecture, the tower is a crisp, pristine object that I love seeing everyday as I walk out the door. This seems to be exactly what Viñoly planned. For him, 432 is meant to offer its residents choices—flexible open plans that allow them to make each unit a home—while also offering the city at large a well composed, highly resolved monument that harmoniously integrates with the surrounding urban grid. For Mies, who was obsessed with eradicating mass in favor of ever more airy volumes, 432 would be a miracle.

This article was publsihed in Forum Magazine by Design Miami.