The cherished dresser in my bedroom was acquired at an auction by Phillips just after 9/11. When I recently discovered that it came from the private collection of John Exelrod, I became intrigued by this connoisseur, who has assembled one of the finest collections of American modernist design. Created in the 20s by Viennese-American industrial designer, Paul Frankl, as a part of his famed Skyscraper furniture collection, our dresser not only looks like one of those chic setback skyscrapers built in New York City in the 1920s, but was also meant to fit the modern lifestyle being lived in one of these buildings. It feels at home in our building which was completed in midtown Mahnattan in 1922. The connection between Frankl’s furniture and the new architecture of New York City was celebrated in the press, we learn in a new publication that announces the transfer of Axelrod’s collection to its final home, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, to which it was entirely gifted (along with his other collections of African-American art, Graffiti Art, Memphis, and Schneider Glass).

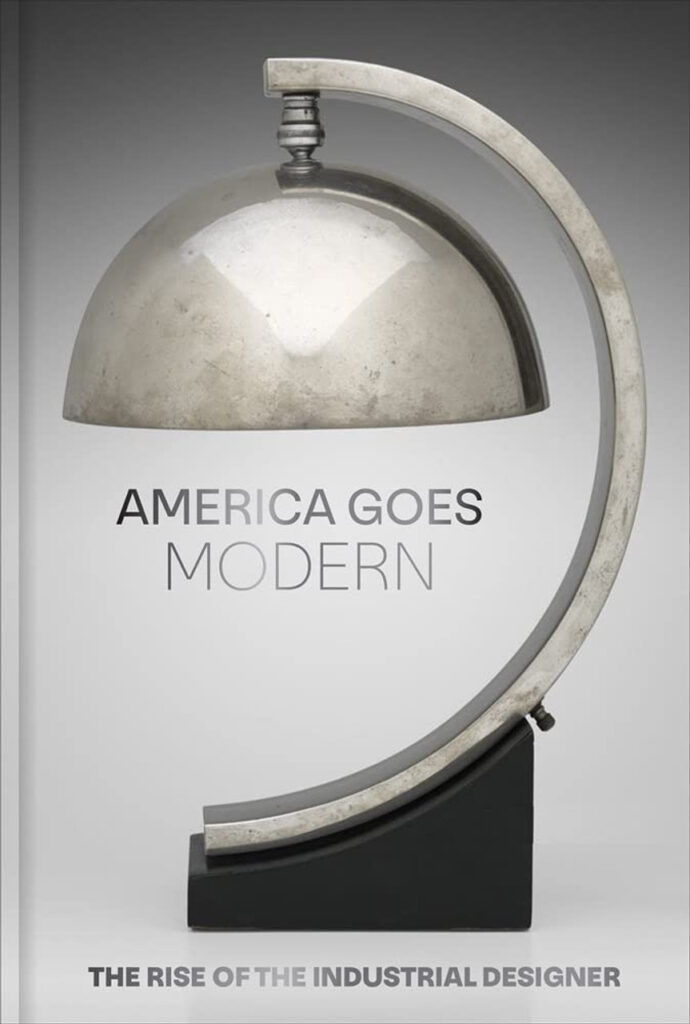

The power of America goes Modern, the Rise of the Industrial Designer, co-authored by Nonie Gadsden, the Museum’s Senior Curator of Decorative Arts and Sculpture, is a celebration of the crème de la crème in design created during that period—also known as the ‘Machine Age,’—from Axelrod’s collection. An attorney and businessman, he has become a passionate collector who announced as a student at Harvard Law School in the late 60s that his ultimate goal was to own the best private collection of American modernism. This was long before the leading forces in American modern design were hailed as heroes of modern culture; an impressive list including Norman Bel Geddes, Manning Bowman Company, Jules Buoy, Donald Deskey, Paul Frankl, Earl Harvey, Ianelli Studios, Belle Kogan, William Lescaze, Erik Magnussen, Peter Muller Munk, Gilbert Rhode, Victor Schreckengost, Walter Dorwin Teague, Harold Van Doren, John Vassos, and Kem Weber.

The book delves deep into the sophisticated life of the inter-war years in those new and polished New York skyscrapers. From the cocktail parties and the New York jazz nightclubs that were often featured in Life Magazine, to the chic, elegant consumer goods designed to look sleek and modern, fabricated in polished metal and plastic, to the streamlined cars owned by Hollywood elite, famously created by American automotive designer Harley Earl for General Motors, to life in the metropolis where everything was informed by the speed, stylish cameras, radios, record players, where everything ‘Design for the Machine,’ as the name of the 1932 influential exhibition in Philadelphia. What a magnificent time when America had become recognized as a powerful artistic force with design of its own identity.

The text is not as powerful as the depicted images and the narrative. After several recent publications on this same topic—Making America Modern: Interior Design in the 1930s, by Marilyn F. Friedman; A Modern World: American Design from the Yale University Art Gallery, 1920–1950, by John S. Gordon; Paul T. Frankl and Modern American Design, by Christopher Long; and other monographs– I am eager to learn more, especially as a New Yorker, about that magical time when transportation, travel, technology and advertising changed the face of modern life. More of original reserach, of the still unknown. Much of the text is based on facts and events known and publsihed before. My love for Machine-Age American design, largely inspired by my colleague James Zemaitis whose passion and knowledge for that particular period has been infectious, makes me wish that people all over the world would start appreciating it, collecting it, living with it. It is one of my long-standing disappointments that, while French Art Deco has been appreciated and collected worldwide, ‘American Art Deco,’ to which it is sometimes erroneously referred, has remained largely unnoticed except by a small circle of American collectors.

If you like to dream, buy this book. The plot is gripping, and flipping through the pages, you are introduced to the sublime and glamourous face of life during the Great Depression. It allows you to dream like Cecilia, in Woody Allen’s romantic fantasy The Purple Rose of Cairo, set in the Great Depression of the 30s, who goes to the movies to dream.