As noted in Part I of my Celebrating Kogei editorial series, I recently had the pleasure of visiting Japan on a journey of discovery, traversing rivers, forests, and mountains to meet the country’s most celebrated kogei artists. In Part II of this series, I wish to spotlight the amazing talents I encountered who work in the medium of ceramics.

The paramount lesson I learned on my trip is that the term “Japanese Ceramics” encompasses such an expansive body of work as to be practically meaningless—too imprecise to capture the rich diversity of the practice today. Throughout Japan’s history, the ceramic arts have held a venerated place in the wider culture. By the 17th century, Japan’s porcelain production had become globally recognized for its unparalleled excellence, and later, in the 1920s, its Mingei Movement, played a key role in inspiring similar studio craft revivals in Europe and the US. Continuously evolving ever since, Japanese ceramic arts in the 21st century have taken on a vast array of manifestations, spanning a multitude of technical, material, and narrative approaches.

In seeking out the finest examples of contemporary ceramics in Japan—including earthenware, stoneware, and porcelain—I visited studios in Kyoto, Kanazawa, and Imbe. Some artists employ wheels and others sculpt the clay by hand; some use traditional and experimental glazes and others allow wood ash to paint the clay; some were brought up in multi-generational family practices and others sought out training in schools and apprenticeships with masters. In Japan’s past, ceramics skills were passed down through the generations within regional workshops, and the names of individual artists were not known beyond their immediate communities. Now, sons and daughters often create very differently from their forebears in pursuit of technical innovation, personal expression, and greater alignment with changing lifestyles and values.

While many of the ceramic artists working in Japan today are more interested in pursuing novelty than those who came before them, they remain highly respectful of their heritage—especially the immense legacy of Japanese teaware. While devoting their lives to pushing the boundaries of ceramic arts, they carry forward many age-old traditions, including beautifully integrating their living and working spaces under one roof. What follows are profiles of the amazing practitioners—seven of Japan’s greatest living ceramic artists—who generously opened their doors and hearts to me, hosting me over a cup of matcha while demonstrating their techniques and recounting their stories.

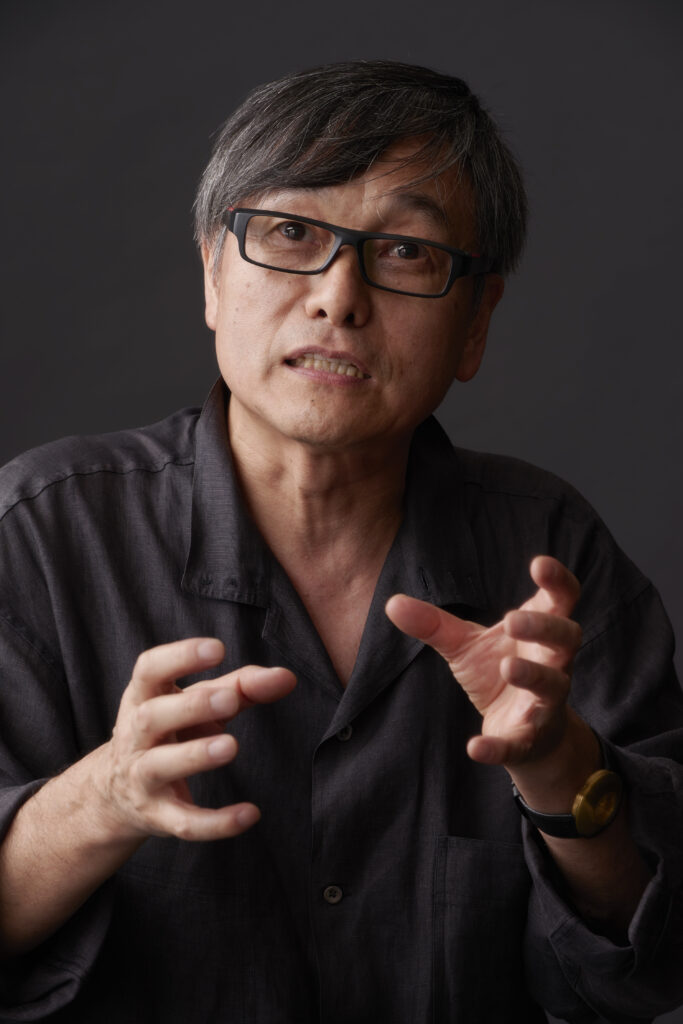

Ōhi Toshio Chōzaemon XI (b. Kanazawa, 1958)

Creating a tea bowl, according to Ōhi Toshio Chōzaemon XI, is not a mundane, humble process. The experience is spiritual, meditative, and creative, and the result should be a work of art. As an 11th generation ceramics master in the Chozaemon dynasty—renowned for exceptional teaware for 350 years—Ōhi is committed to developing his own philosophy while also preserving his family’s profound legacy. This means that he makes only a handful of bowls per year; each handcrafted to be one-of-a-kind and fired one at a time in the same tiny kiln that was used by the dynasty’s founder in the 17th century.

In 1990, Ōhi turned the family’s historic samurai home into a museum and, later, commissioned Japanese starchitect Kengo Kuma to design an addition. Today, it is one of the most sought-after destinations for visitors to Kanazawa. Kuma integrated his contemporary design within the site by using traditional Kanazawa materials, like paper, bamboo, lacquer, and gold leaf. During my visit, I enjoyed sitting in the spacious tearoom, a 500-year-old pine just outside the window, watching Ōhi illustrate his process as he spoke about his heritage, his vision, and the essence of the tea bowl.

Ōhi has two siblings; his younger sister was a ballet dancer before she died at a young age from illness, and his brother became a tea ceremony master. As the eldest son, according to the traditional custom, he succeeds the house as the torchbearer for the lineage. He clearly remembers his grandfather teaching him the significance of shaping a tea bowl by hand, because the trace of the hand reveals the creator’s heart and spirit. “No matter how much time passes,” Ohi says, “the sensibility that the artist puts into his works may be the continuation of the story between the artist and the people who use the bowl.”

As a young man, Ōhi wanted to escape the traditions that dominated his upbringing in Kanazawa, including his family’s samurai house and kimonos. But after some years away, first in Tokyo for undergraduate studies and then in Boston for graduate school, he found himself longing for home. Exposure to the international art world—such as seeing his family’s tea bowls in prestigious US museum collections—inspired him to embrace his birthright and carry the legacy forward.

Hashimoto Machiko (b. Kyoto, 1986)

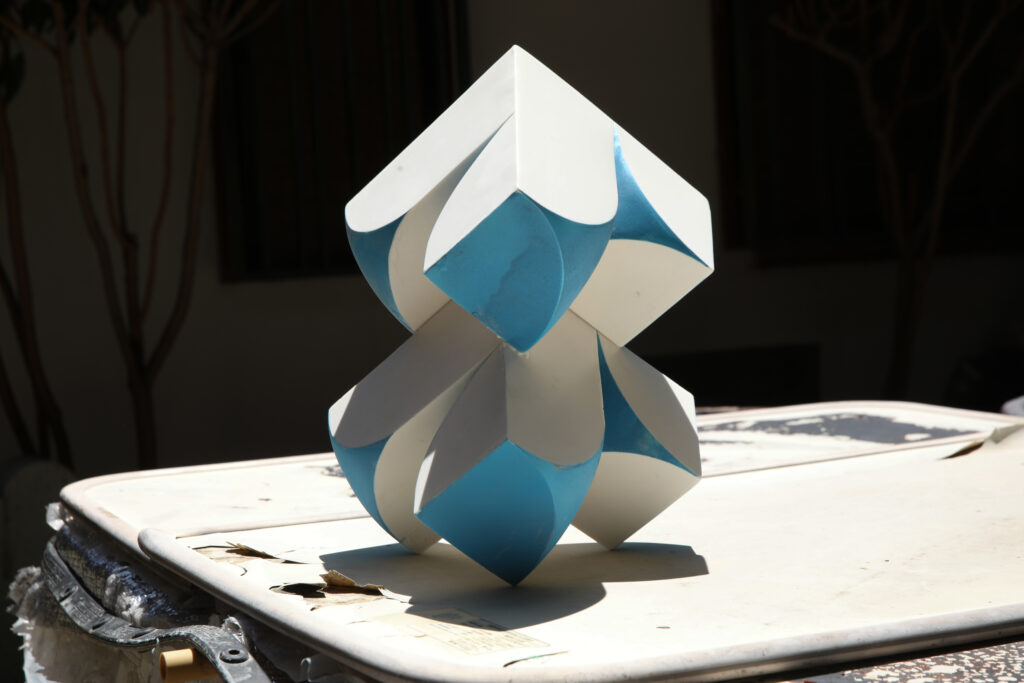

Hashimoto Machiko is the youngest kogei artist I met on my journey. For her, becoming a ceramicist was an early childhood dream. Today she is a professional artist based in Kyoto specialized in new approaches to traditional blue-and-white porcelain. In her home-studio, which she shares with her husband, ceramicist Tanoue Shinya, Hashimoto creates enormous vessels in forms inspired by flower blossoms and buds. Blue, she tells me, has been her favorite color as far back as she can remember, calling it “the color of life” and a symbol of the sky, sea, and life-giving water. Blue, she feels, connects her to nature, and with it she expresses the cycle of life in the most optimistic, dreamy way.

Hashimoto clearly recalls her first encounter with clay at 10. Growing up, she dreamed of making vessels for chic cafes. But after studying ceramics at the Kyoto Saga University of Arts, she began to see clay’s potential for artistic expression beyond the functional and the everyday. She realized that she had to find her own voice, to discover new ways of working with clay. Through persistent research, exploration, and vision, she began to create original ceramic art with her chosen materials: semi-porcelain (white earthenware) and zaffer, a cobalt oxide that allows her to achieve the deep blues she admires in nature.Hashimoto’s hometown, Kyoto, has a special place in her identity as an artist—she’s never lived anywhere else. Kyoto’s rich history inspires her. It is, she says, “the city where tradition and innovation coexist.” Local gallery Sokyo has been her main vehicle to international audiences.

Her work is magical, not only because her blue-and-white flower forms capture that elusive moment when a bud becomes a flower but also because her carving technique captures the energy and passion she brings to her craft. Each of her works is different, the result of the labor intensive process she developed shaping slabs of clay covered in plastic. Each is fired and, after the blue zaffer is applied, fired again. With their enormous scale and rich texture, her pieces have the power to transform spaces.

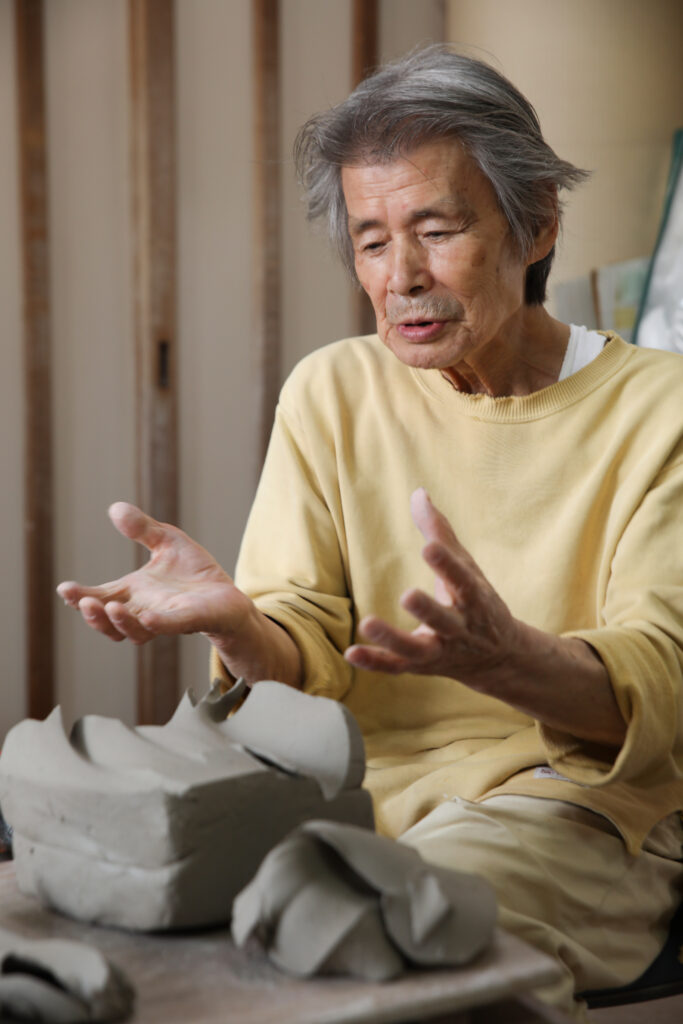

Isezaki Jun (b. Bizen, 1936)

Since the 8th century, Bizen has been one of Japan’s most celebrated sites of ceramic production—synonymous with the allure of Japanese clay utensils. The star of Bizenware production today is Isezaki Jun, who was named National Living Treasure for his mastery of the craft and his role in reviving ancient Bizen techniques that were beginning to fade away. Part of a distinguished family of potters, he, his father, his elder brother, and his rising-star son, Isezaki Koichiro, all practice ceramics in the family home-studio in the village of Imbe.

Bizen pottery, produced exclusively in Imbe, has a distinctive appearance and legacy. Featuring an unglazed reddish-brown tone, the vessels are typically shaped on wheels and then slowly wood-fired in enormous stone kilns, called anagama. The interior of these special kilns are constructed in a series of chambers, which hold the pottery during its two-week-long firing process as wood ash settles on the clay and forms a natural, warm-hued glaze. The pottery is then cooled over another two weeks. The finish of each piece is determined by their position within the kiln, and master potters can predict the results by the path of the flames.

Bizenware is the ultimate expression of Japan’s Mingei Movement, which in the 20th century celebrated handcraft in its simplest, most authentic form. In the 1970s, proponents of the movement resuscitated appreciation for the age-old ceramic arts of Bizen and inspired a new generation to become practitioners. Today, dozens of shops are scattered throughout the area, offering Bizen-style tea bowls, cups, and other objects to enthusiastic tourists seeking authentic artifacts of Japanese culture.

Working within the tradition and credited with reviving the anagama firing method, Isezaki has nonetheless developed his own bold, sculptural style. His pieces are hand built rather than wheel thrown, resulting in forms that are more daring, dynamic, and sensual than historical teaware. At age 87, he certainly knows his craft better than other living artists, and, with the support of his family, continues to create to this day. Wahei Aoyama of A Lighthouse called Kanata graciously arranged our visit with Isezaki, who hosted us in his beautiful showroom appointed with furniture designed by George Nakashima (whom he met in the 1970s). Isezaki was delightfully animated and generous with his time as he explained the innovations he brought to the legacy of Bizen. Notably he mentioned that Bizen clay has been used up and can no longer be found. But Isezaki has collected enough to pass on to the next generation.

Kakurezaki Ryūichi (b. Nagasaki, 1950)

Another spectacularly prolific and accomplished star of Bizenware is Kakurezaki Ryūichi. Born in Nagasaki, he is not native to Imbe and some say that for this reason he was able to stretch beyond historical constraints while also remaining true to tradition. He has forged a new, simple yet poetic vocabulary in clay, which the potters of Imbe often call “futuristic.”

After high school, Kakurezaki pursued a career in graphic design in Osaka. But at age 26, he relocated to Imbe to become a ceramic artist and enrolled in a local technical school. Upon graduation, he landed an eight-year-long apprenticeship with Isezaki Jun. There he built his foundation in the traditions and techniques of ancient Bizen pottery while also developing his personal vision. This vision, he tells me, is not a rebellion, as he has never intended to revolutionize his field. Finding inspiration in the world around him and following his instincts, though, has given him the confidence to pursue new directions. While continuing to craft functional objects for everyday use in line with the local way, he has introduced a fresh approach that he hopes, in his words, “gives back to Bizen.”

The complexities of producing Bizenware require practitioners to develop extensive experience and skill sets. Every firing, I learned, is planned months in advance down to the last detail. Kakurezaki draws the works he wants to create before forming the clay. Once a year, he uses the enormous red pine-fueled anagama kiln in the back of his studio to fire around 100 pieces at time, each strategically placed in various areas of the chambers to achieve the desired effect. At age 73, he never fails to realize his vision.

As Michael David Carrasco, Associate Dean of FSU’s College of Fine Arts told me: “A key satisfaction in collecting contemporary Japanese ceramics comes from the dialogue between centuries-old traditions and aesthetic innovations. Kakurezaki’s work exemplifies this exchange. His sculptural, angular vocabulary, complemented by his experiments with lighter color and coarse mountain clay, contrast with the organic kiln effects… challenging the viewer to immerse themselves in the seductive form and tactility of the clay body.”

Nakamura Takuo (b. Ishikawa, 1945)

The second son of prolific potter Baizan II, Nakamura Takuo was born into ceramics but did not pursue the craft until he was well into his 30s. After opting to give up his corporate career, he went home to apprentice with his father, who specialized in Ninsei and Kenzan teaware. Like others profiled here, he soon realized that he wanted to develop his own voice in clay.

Growing up in a family of Kanazawan craftspeople during the postwar years, he says, Nakamura was immersed in the traditional life and culture of kogei artists. Tea ceremony and Noh theater connoisseurship was a prerequisite for anyone seeking a kogei profession. Today, he enjoys a freedom to be more individualistic, living in the modernist house that he built on the family’s property, next door to his ceramicist younger brother, Nakamura Kohei.

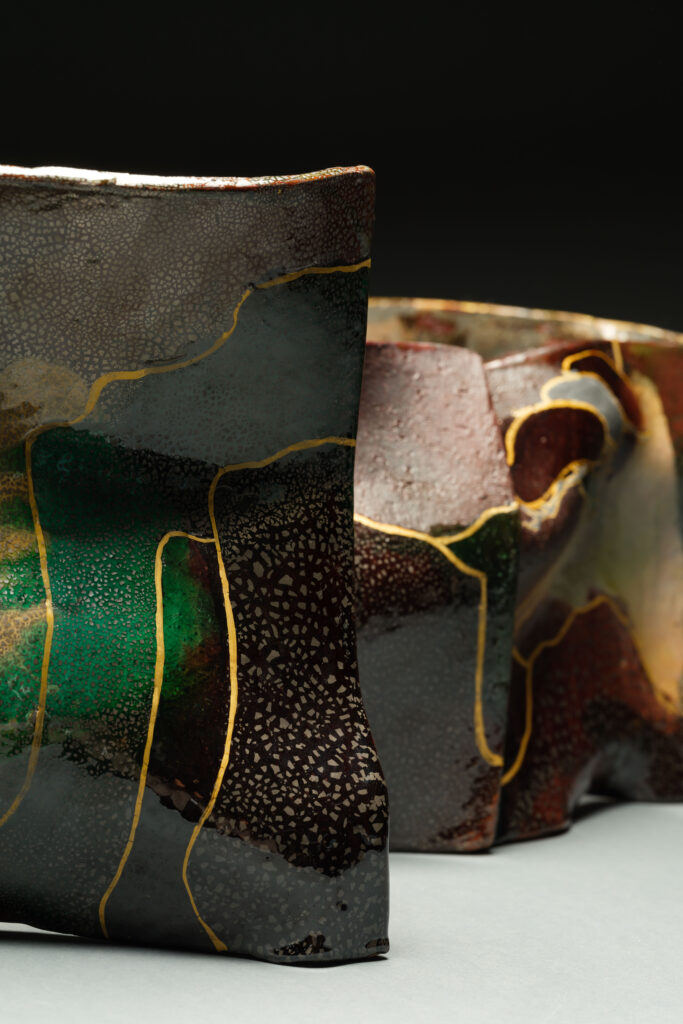

Nakamura’s mantra is that objects can be fulfilled only in relation to space. While sharing a studio with his father for 20 years until his death, he steadily developed this personal perspective on his work, which has since made a tremendous contribution to the story of Japanese ceramics. His current practice draws on traditional, lavish Kuntaniware techniques to produce works of art with a powerful, contemporary identity. His reinvention of historical overglaze methods together with his holistic design thinking result in objects that make you see the fields of ceramics and design in a new light.

When he entered the world of ceramics in the 1980s, Nakamura immediately began to deconstruct forms and explore how unexpected shapes can transform the viewer’s experience of the surrounding space. He discovered the potential of clay slabs that have been cut, slashed, and dropped on the floor to give rise to functional objects with sculptural forms. He knew he was on the right path when the Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired one of his pieces in 1991—the institution’s first acquisition of a living artist in 25 years.

During the 1990s, inspired by Postmodernism, Nakamura developed his iconic Vessel Not a Vessel series, the abstracted forms of which invite users to determine how they are used. In the next decade, in the new millennium, he developed his Almost a Vessel series, which arose from his reflections on how, as he says, “the reality of a vessel does not lie in its appearance but in the space it holds within.” He began to approach the space of objects like the space of architecture.

Nakamura’s multi-level home, designed 28 years ago by Japanese architect Hiroshi Naito, illustrates the artist’s approach to space. As you walk through, you truly feel how the objects within illuminate the surrounding architecture and vice versa.

Hayashi Yasuo (b. Kyoto, 1937)

At age 87, award-winning Kyoto-based artist Hayashi Yasuo is one of the most prolific ceramicists in Japan, well known for his rejection of convention. Never officially trained in ceramics, he has nonetheless built a successful career as an artist working outside of Japan’s traditional ceramics system.

A pioneer in non-functional ceramic arts in Japan, Hayashi considers clay an ideal medium for making provocative artist statements. He has been developing his unique vision for marrying ceramics and sculpture since the 1950s—when such groundbreaking ideas were widely deemed unacceptable. He wasn’t impressed by the Mingei Movement’s ideas around utilitarian craft revival.

Throughout his eight-decade career, Hayashi has worked in the same studio, on the second floor of his home, tucked behind a façade on the famed Gojōzaka street. Near the Kiyomizu-dera Temple, this area has supported a concentration of ceramic studios since the 17th century. Today, his ceramicist son works under the same roof.

Hayashi studied painting in the traditional Nihonga style. During WWII, however, he was forced to leave school and join the Naval Air Force. Afterward, when the economy was destroyed and people were falling into poverty, he went to work at his father’s ceramic studio. Having little interest in throwing vessels on the wheel and inspired by avant-garde art movements of Europe, he focused on developing his own spare and abstract vocabulary in stoneware. At 20, Hayashi cofounded Sōdeisha, an influential vanguard artist collective based in Kyoto that remained active for five decades. Its members sought to push the boundaries of clay as a medium for fine art and ultimately succeeded in giving potters in Japan a new professional identity. Sōdeisha principles—creating non-functional, biomorphic, slab-built sculptures in clay—are clearly present in Hayashi’s work to this day.

What a memorable experience I had, sitting next to the man who liberated clay from vessel-making in his intimate home studio. As he demonstrated his techniques for creating daring forms, he spoke about struggles following such an unorthodox path—it was clear for him that he could never achieve Living National Treasure status, which is reserved for potters who replicate traditional techniques. At the same time, his work was excluded from the art world because it was seen as “craft.” Now that he has an exhibition at Sokyo Gallery scheduled to open next spring, with his 88th birthday soon approaching, he feels that he has finally triumphed over the impossible. I couldn’t help but admire this humble, sweet, independent, and visionary spirit.

This article was published today in The Forum Magazine. I would like to thank those whose efforts made this tour and published article possible: Wahei Aoyama and Kumiko Sunahara of A Lighthouse called Kanata; Atsumi Fujita of Sokyo Gallery; Nana Onishi of Onishi Gallery; and the inspiring artists who opened their studios and generously hosted me and told me their stories.