When I received Amos Oz’s autobiography ‘A Tale of Love and Darkness‘, I was about to leave for Africa. I took the book with me, and during a long stay at the Victoria Falls Hotel in Zimbabwe, curling up on a hammock overlooking the dramatic views of the Falls, I got lost in his world. Half-way through the book, it was clear it would make my top five list. When David Kroyanker, the architectural historian of Jerusalem read the memoir, he felt the same, and decided to make a special gift for Oz’s 80th birthday, but Oz died six months’ before the completion and never learned of Kroyander’s gift, ‘The Jerusalem of Amos Oz’.

There are many layers in the story of Oz’s family saga and tragic childhood in the shadow of his mother’s depression and her consequential suicide. The layers include the story of the Zionist dream and the birth of the State of Israel, which are beautifully interwoven in this extraordinary self-portrait. One of the aspects that connected me to the book are the nostalgic narratives of pre-WWII Jerusalem. It was a multi-faceted, cosmopolitan, elegant bohemian city, a city of cafes, theaters, and intellectuals, feeling more like Vienna and Berlin than a dusty place in the Middle East. ‘At every table,’ Oz recalls, ‘sat meticulously dressed ladies and important men who spoke among themselves in low voices. Waiters and waitresses in white jackets, an ironed cloth folded on their arm, hovering among the tables and serving the guests piping hot coffee.’ It is the nostalgic image that is cemented in the Israeli collective memory, the Jerusalem where my father spent his childhood and adolescent years with his family, immigrants from Munich.

In ‘The Jerusalem of Amos Oz,’ published this year by Keter, Kroyanker seeks to reveal the sites and buildings which Oz illustrates in ‘A Tale of Love and Darkness.’ Like Oz, he was born in 1939, and like him, grew up in British Mandate Jerusalem. Both lost a parent early (Kroyanker lost his father at 6; Oz lost his mother at 12), and both were lonely boys in the rapidly changing city. While Oz left his family to join a kibbutz, changed his name, and became a political activist, Kroyaner stayed in Jerusalem, studied architecture, and worked in the urban planning department of the Jerusalem Municipality. He became the ultimate expert on the built fabric and its history, publishing dozens of books on Jerusalem’s neighborhoods and their architecture.

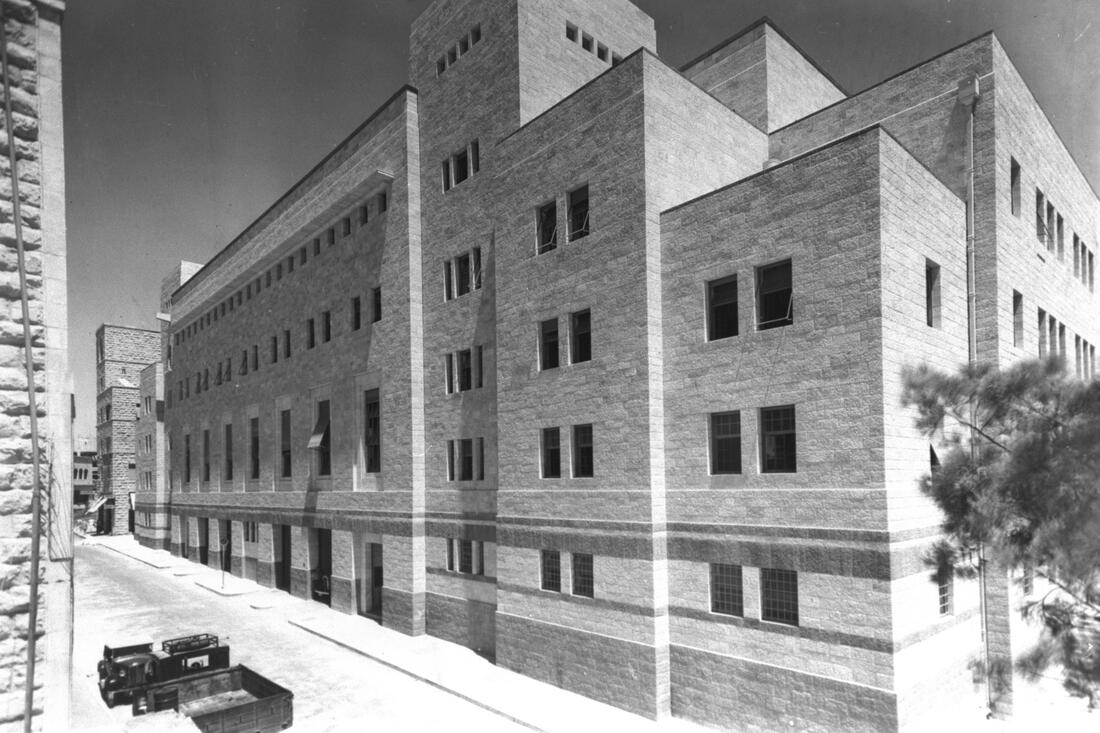

‘The Jerusalem of Amos Oz’ provides the paths along which Amos Oz walked as a child, following the footsteps of his memories, and bringing a new life to this remarkable memoir. The route that mostly captured my imagination is where Oz walked every other Saturday with his parents, visiting his father’s uncle, the renowned historian Joseph Klausner, who lived in Talpiot, not far from my father’s home. The expansive house, we learn from Kroyanker no longer exists, along with many other touchstones of Oz’s Jerusalem. The Tachkemoni School, where he studied beginning in second grade; the Edison Theater, which was built in 1932 and became the city’s cultural center during his childhood; as well as both the Rex and Studio cinemas were all demolished and disappeared together with the spirit of those days.

As a historian who has devoted his career to the study and documentation of Jerusalem’s built fabric, Kroyanker shows us Jerusalem through the eyes of Oz: complicated and dark, a gloomy city of longing. But he also gives us a glimpse into neglect and destruction. ‘The Jerusalem of Amos Oz’ is a rare account of the most spiritual place on earth before it was overwhelmed by forces of Messianism and invaded by the ultra Orthodox community. Kroyanker shows us not the Jerusalem of synagogues and concrete walls, but rather the secular, bourgeois place of poets, scholars, and books.