Today, this is to R. Louis Bofferding, the New-York-based dealer whose exquisite showroom attracts museum curators, tastemakers, and those who seek to live with the finest historical design. His knowledge of design history brings Bofferding to the the world’s auction houses where he finds historical masterpieces of museum quality that auction specialists misattribute. He is the epitome of the traditional dealer who discovers pieces of great significance, engages in scholarly research on each piece he sells, and then offers them up with essays and rediscovered provenances. Louis Bofferding connects his clients with the past. You may know his name if you are a reader of Architectural Digest, where he publishes articles on the history of decorative arts.

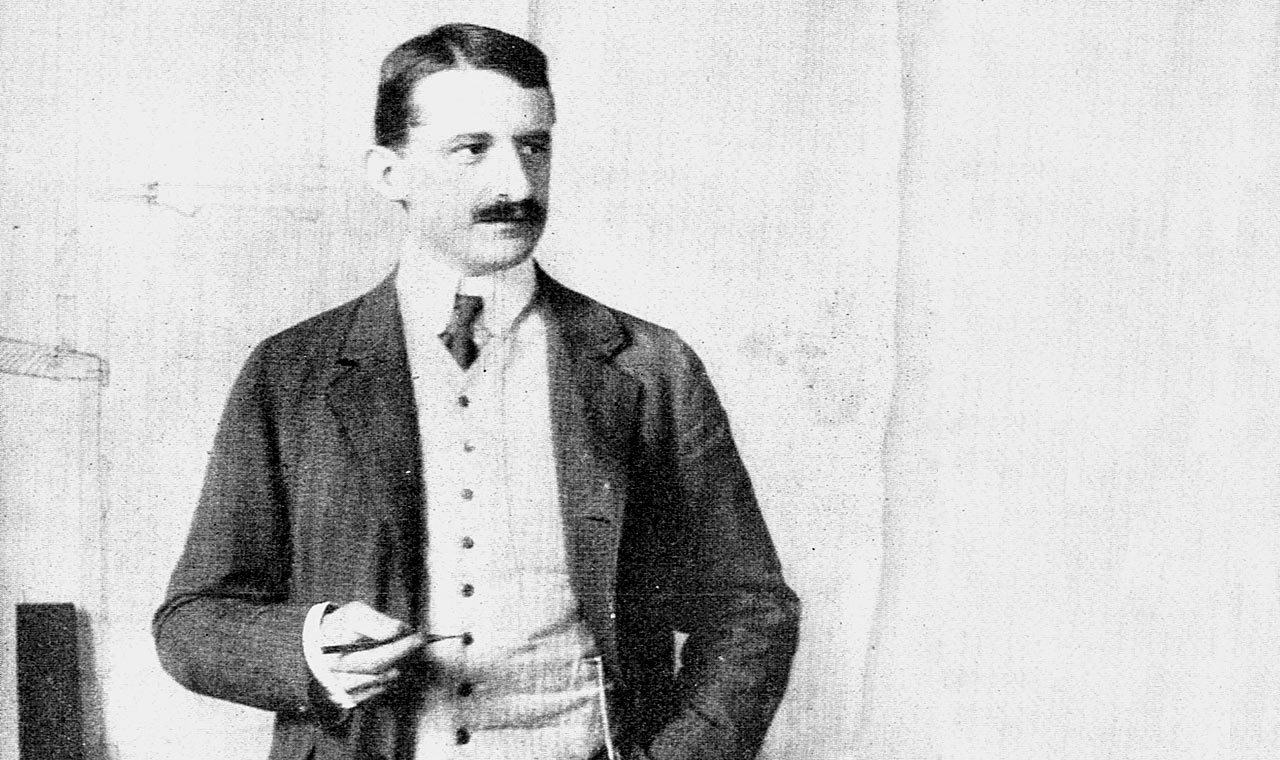

I asked him to recommend one of his special pieces for this post, and he selected a sideboard designed by Bruno Paul in 1928, which was produced by the Vereinigte Zoo-Werkstätten (above), so-named because it was located near the famous Berlin Zoo. Paul is far from being a household name like his contemporaries Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius, yet the German architect was one of the most important pioneers of the Modern Movement in Weimar Germany. His work came to embody the evolution of modernism. In addition to taking part in the foundation of the Jugednstil movement, Paul was a founding member of the national organization, the German Werkbund, designed modernist buildings, graphics, furniture, and interiors for the North German Lloyd ocean liners. He remade a school for fine and applied art in Berlin into a rival of the Bauhaus, but his own career there was effectively terminated when the Nazis came to power in 1933.

This sideboard is not only beautiful in its simplicity and craftsmanship, but it is also a perfect example of Paul’s successful concept of modernist furniture being more suitable to factories and the workplace than domestic use. For homes he created a simple, handcrafted furniture line largely modeled after the historical style of Biedermeier, popular in the German-speaking world a century earlier. Historians have traditionally chosen to ignore this direction in German modern design because it embraced hand-made processes. Yet Bofferding tells me that when reading period design magazines it becomes clear that Paul’s crafted line was far more successful in his day than the avant-garde metal pieces that we admire today.