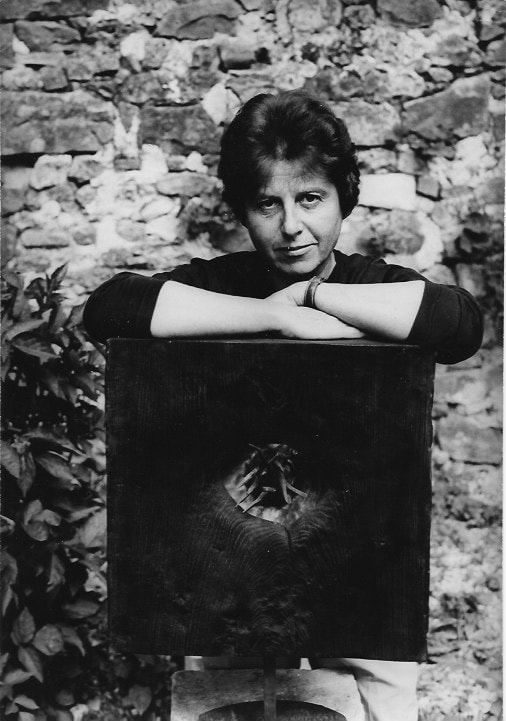

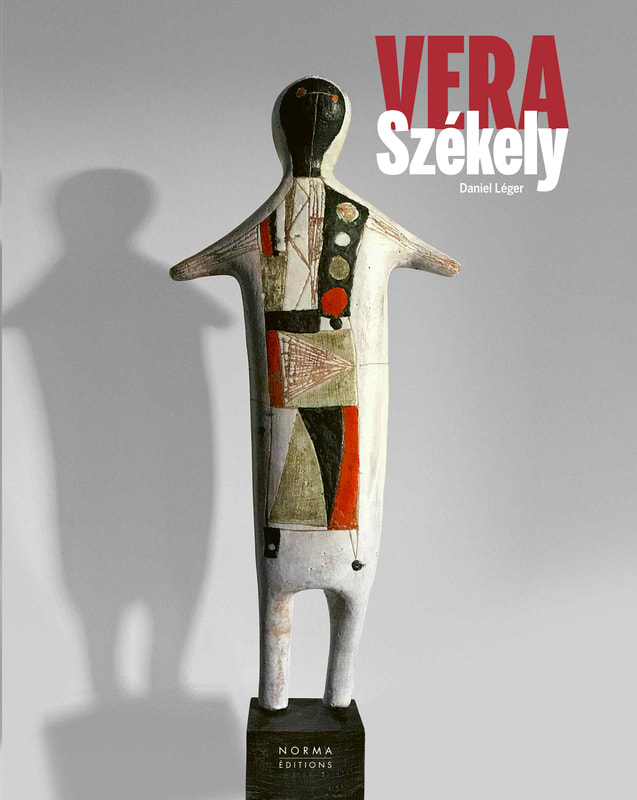

Vera Székely has been a hero in the art market for years, but although her oeuvre is multifaceted, complex, and highly sought-after by collectors, her story has remained relatively obscure. A new publication (in French and English) by the writer and avid collector Daniel Léger (published by Norma Editions) comes to shed light on the fascinating life and journey of this mega talented female artist who has often been left in the shadow of her husband, and thus was somewhat ignored by those writing the history of art. The book provides a detailed chronology of her career, from the naïve ceramics of the postwar years to the conceptual art of her later career. It is concluded with a critical assessment of the super individualist and courageous

Székely who paved the way to a magnificent career and fascinating life in the international art world.In the 50s, she focused on clay art and was known for a distinctive graphically-oriented style, while working as a member of the trio ceramics collective Székely-Borderie, established by the Székelys and André Borderie. The style was naïve, colorful, and whimsical, representing the spirit and atmosphere of the postwar era. They created walls, fireplaces, architectural fittings in clay for churches, private residences, restaurants, shops, schools, public murals, along with decorative objects, demonstrating the key place of ceramics in mid-century French architecture and interior design.

In the 1960s Vera Székely turned away from her early ceramics, and her work had become more sculptural, expressive, and conceptual. She sought to free herself from the collaboration with Borderie and Székely, and became interested in the power of clay to achieve spiritual quality, much like her contemporary Ettore Sottsass. She moved to work with wood, salvaged metal, and fiber, experimenting with materials while creating work that was more powerful and less decorative, more abstract and expressive. Another turning point was her ‘structure-tensions’ of the late 70s and 80s, manifested in installations of sails in public institutions, including the Centre George Pompidou in Paris. It is here that Vera Székely was able to give a full expression to her strong sensibility for architecture and interior territories.

The book is a mandatory addition to any art/design/craft library. Through a close discussion and meticulous description of the work and the dynamic evolution of her career, Leger demonstrates that Vera Székely was a giant artist that should be remembered as such. She called herself a ‘plastic artist,’ a term that came to capture her eternal experimentation with materials and technique, and if softness is the expression of femininity, then Vera Székely‘s art was the embodiment of femininity.

Above: Vera et Pierre Székely, table basse, céramique et ciment, 37 x 120 x 40 cm. Collection Magen H. Gallery, New York.