The fact that American ceramicist Toshiko Takaezu (1922-2011) has become the darling of museum curators in recent years is largely because ceramics have their moment. These days everyone is interested in clay objects and they are finally glorified as works of fine art — the contemporary art world, galleries, interior designers, collectors, architects. Takaezu, described decades ago as a ceramicist, was a modernist sculptor, considered today as a part of American Abstract Expressionism for utilizing clay as her canvas. Her work is regularly collected and offered at auctions; last year the collector community was stunned when an example of her stoneware Moon fetched $541,800, setting a new auction record for the artist. The Toshiko Takaezu Foundation was established four years after her death is helpful too. It seeks to preserve and promote her legacy, to renew interest and scholarship, while taking an active role in museum shows and collecting, further establishing her heritage.

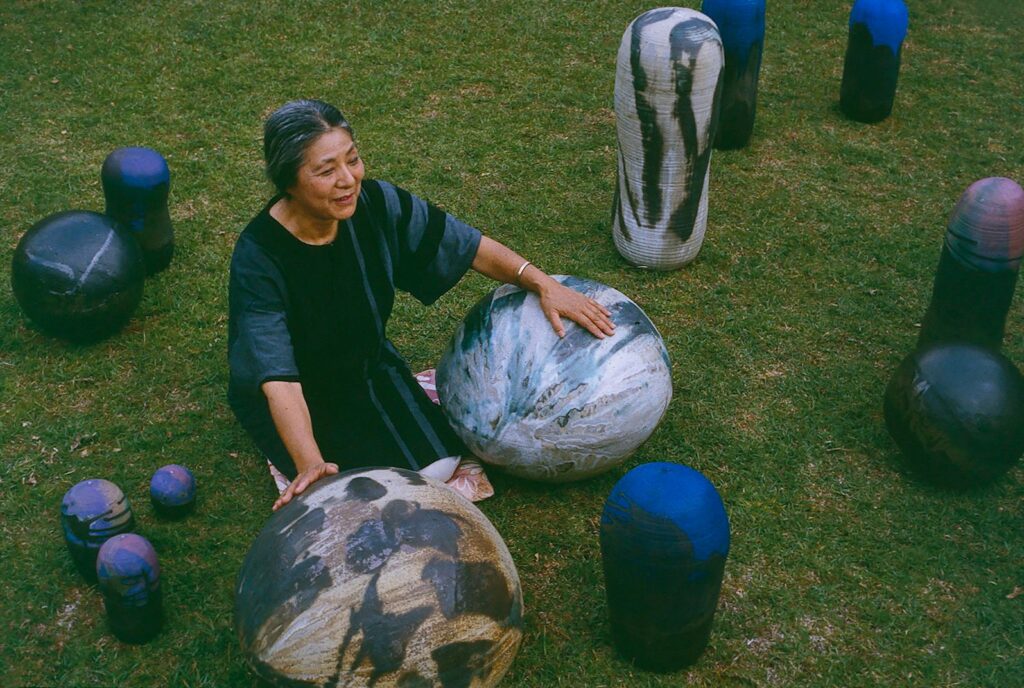

Takaezu’s work is holistic, expressive, often monumental, combining sculpture and painting. Her raw and enclosed forms contain a touch of Zen allure and her spectacularly layered glazes, drips, and abstract brushwork have become her trademark and personal signature. Now that a traveling retrospective, exploring a seven-decade career has opened at the Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, entitled Toshiko Takaezu: Worlds Within, exploring the way she created worlds within her vessels, it is the perfect time to look at the legacy of the woman who was born to Japanese immigrants, grew up humbly in Pepeekedo Hawaii, and created some of the most memorable works in clay of her time.

The connection to the Museum is clear; both Takaezu and Noguchi were Japanese Americans whose heritage and the experience of the Japanese landscape played a central role in their oeuvre, and both shared admiration for one another. Although Noguchi was born in Los Angeles, he lived with his mother in Japan from age 2 to 13 and went back in his 20s. Studying Asian brush painting and pottery in Japan came to shape his artistic voice. Conversely, Takaezu did not travel to Japan until her early 30s, but when she did, the experience was powerful. She stayed for eight months, studied Zen Buddhism, tea ceremonies, and Japanese pottery, and these years had become her lifetime inspiration. Noguchi himself collected her work, but the works in the exhibition came from many public and private collections. This connection between her work and the Museum in Long Island City, established by Noguchi in the 80s is fully experienced on the aesthetic level when you visit the show and see how Takaezu’s clay vessels are glowing throughout the spaces, and vice versa, as they are installed to create landscapes of clay, in her own voice.

While walking through this wonderfully installed exhibition which takes over the entire second floor of the Museum, I was thinking of her contemporary Joan Mitchell, an active member of the New York School and of her textured brushwork canvases. I also thought of another female legend—French designer Charlotte Perriand—because for both, traveling to Japan and living there for months came to shape their aesthetic and artistic vision. In fact, when Takaezu went to Japan in 1955, Perriand curated an exhibition, a Synthesis of the Arts at the Takashimaya department store, in Nihonbashi, Tokyo, and I was wondering if she had a chance to visit one of Perriand most iconic projects.

What I found most compelling about this show was how it displays hundreds of vessels so you can see the power of the single form—the closed vessels—in shaping an intriguing narrative over a lifelong career. Takaezu’s ‘closed’ vessels have become synonymous with her legacy, which she typically grouped into installations, while containing pieces of clay in them. She began this practice after accidentally dropping pieces of clay inside the vessels before sealing it, which she would continue to do throughout her life, wrapping small clay pieces in inscribed paper with hidden words inside her pots, creating worlds within. The poetic quality of her clay sculptures has become more apparent and powerful as they glow in the Museum with the beautiful Japanese garden seen from inside. “You are not an artist simply because you paint or sculpt or make pots that cannot be used,” she said. “An artist is a poet in his or her own medium. And when an artist produces a good piece, that work has mystery, an unsaid quality; it is alive.”

While Takaezu has explored many mediums such as weavings, bronze, and paintings, all of which are included in the show, it is clear that it is with clay that she creates the most interesting, innovative, and personal expressions. She was an educator with a deep passion for teaching. Started teaching at the YWCA in Honolulu, she developed a career in education first at the Cranbrook Academy and then at the Cleveland Institute of Art before she settled in New Jersey and established a studio in an old farmhouse in Quakertown, NJ. She was a strict teacher who expected her students to stand up to her hard work routine. “it doesn’t make any difference-there is no difference between your work, your cooking and the garden. They’re all the same,” she said in the oral history interview by the Archives of American Art of the Smithsonian. “You have to put yourself into it. The result won’t happen unless you are in it. I don’t like people to pull weeds if I don’t like them, if they just pull weeds for the sake of pulling them. “

The exhibition will be open through July 28th before traveling to the the Cranbrook Art Museum (2024–25), the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (2025), and the Honolulu Museum of Art (2026).

Center of Hawaii, Honolulu, March 22; April 12, 1967. © Family of Toshiko Takaezu.

Amazing work ! Thank you for sharing this ART. My son is also an ardent fan of Noguchi .He is half Japanese and half Canadian

(caucasian )He learned to sculpt in Pietra Santa , Italy . His name is Kent Laforme and has sensibilities like these artists. His website is below.

Thanks.