Pauline Baer de Perignon, a Parisian educator of writing workshops, succeeded against all odds in retrieving important works of art which belonged to her family and were confiscated by the Nazis. Her remarkable journey is told in The Vanished Collection, a new volume in English, published by New Vessel Press. For my generation, third generation Central Europeans—the grandchildren of those Jews who fled Nazi Germany, Austria, Italy, France, Breslau—there is special cultural memory that is rooted in an eternal sense of loss and in an everlasting search to uncover and reconstruct our families’ histories and their lost worlds. ‘Every family,’ Baer de Perignon writes, ‘has its paradise lost,’ and in her case, it is art which was looted during the war.

For my grandparents’ generation, some managed to escape physical annihilation by emigrating; others were sent to concentration camps, but all experienced tremendous loss. While in Europe, they constituted a major force in the corporate world; many were leaders in banking, publishing, industry, and culture. They were highly educated, enjoyed economic success, resided in elegant homes, collected art, and regularly attended concerts of classical music and opera. One day it was all over and they were displaced, forced to leave this golden age of prewar Europe and to be isolated from the lives they knew.

Questions related to heritage and belongings have come to be a part of the identity of my generation. I remember visiting Munich for the first time at age 21, standing in front of the elegant apartment building on the corner of Schumann Street and Prinzregentenstraße, a noble middle-class avenue and the seat of Munich’s Jewish bourgeois, where my grandparents had once lived. It was more restrained, elegant, and quiet than I would have imagined, more urbane, the cradle of upper middle class Jewish life. Adolf Hitler lived there, too. My father’s cousin, historian Edgar Feuchtwanger depicted the time Hitler moved there in his bestseller, I was Hitler’s Neighbor. It is where my father spent the first seven years of his life and I remember standing there on that corner and trying to imagine how this apartment looked—the art, the rugs, the furniture, the kids’ rooms. I remember closing my eyes and trying to think about that day, when the entire family was compelled to leave this place of comfort, and started their difficult journey to Jerusalem, where they finally settled in a house in Talpiot, overlooking the Dead Sea. I wondered if they knew that they would never be back, that this beautiful life would become a part of their painful memory. It is a syndrome of my generation to wonder what was looted from our families, but to most of us, these wonders reside only in our dreams.

To Pauline Bauer de Perignon, these wonders materialized in the most fascinating journey to achieve restitution of stolen works of art, the ‘Vanished Collection.’ It all started when she discovered that ten works of art in her great grandfather’s legendary art collection were not sold in an auction, as had always been believed, but had been looted. Her remarkable success to restitution demonstrates that the most important factor in any investigation of this type is to reconstruct the personality, customs, taste, daily lives, and the state of mind of her ancestors, in addition to piecing together the events that had led to the Nazis’ confiscation of the art, just like piecing together the most intricate puzzle imaginable. At the end, when she was able to trace the roots of these works of art to the public collections they called home, when she found the provenance and filled the gaps, the clear picture of the fate of her great grandfather’s remarkable collection was revealed.

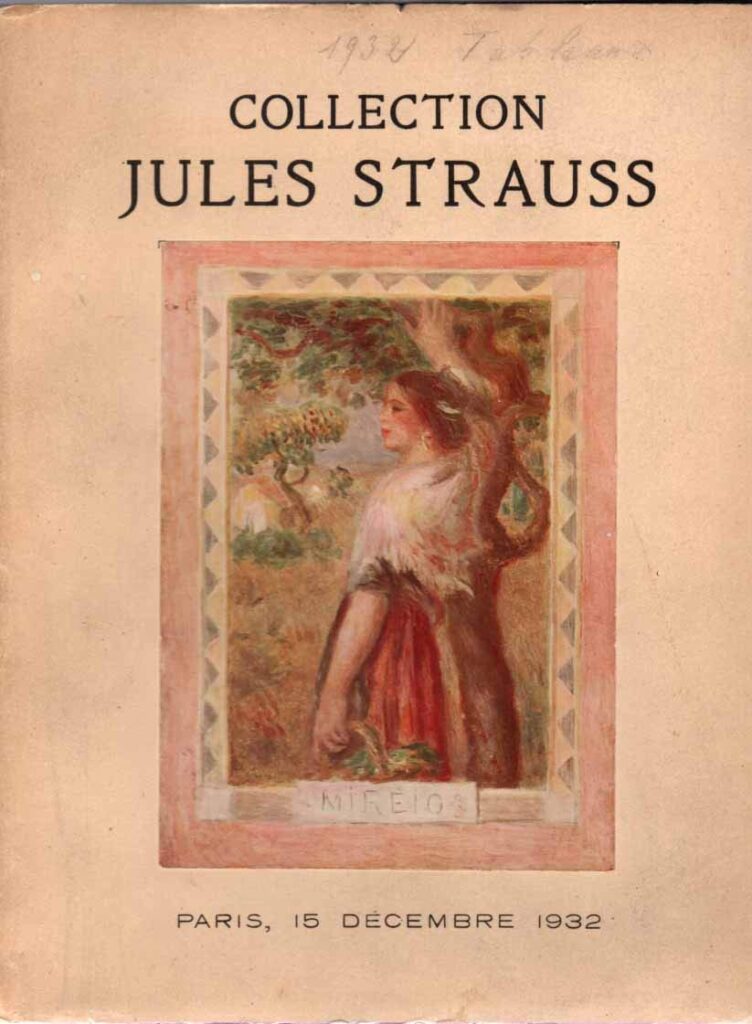

His name was Jules Strauss (1861-1943) and he famously assembled one of the best art collections in history. He lived on the Avenue Foch in the 16th arrondissement of Paris, also known as one of the most prestigious and expensive addresses in the world, home to many grand palaces and the families with the names of Onassis and Rothschild. He collected both Old Masters and modern art by Monet, Degas, and Cezanne. His collection was sold at auction three times, starting in 1932, and the catalogs of these auctions—still considered among the most important sales in history—can be easily obtained online. Baer de Perignon spent years in archives, examining Gestapo records to discover what really happened in 1942. She is taking us through a complicated and long journey of discovery and the attempt to reclaim her family’s possessions seized by the Nazis. She needed to obtain proof of persecution in order to get restitution. That she did not have.

This book should be read by anyone with even the slightest interest in the ‘third generation,’ in art theft, in the creative imagination of investigation, in the intellectual life of interwar Central Europe, and by what it meant to be alive during the Nazi era.