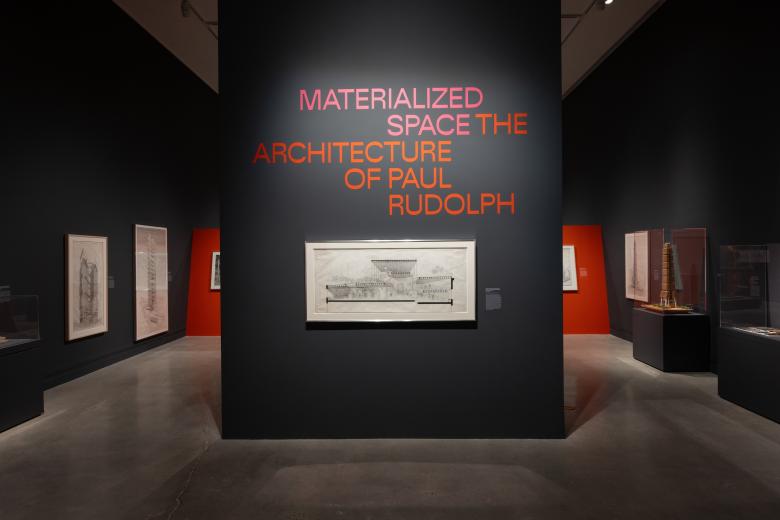

Last week I attended the opening night of the exhibition Materialized Space: The Architecture of Paul Rudolph. As I witnessed the entire architecture community sip cocktails and view the exhibit, it felt as if the Museum had entered a new age under the wings of Abraham Thomas, The Met’s Daniel Brodsky Curator of Modern Architecture, Design, and Decorative Arts. After all, it has been 52 years since its last architecture exhibition, devoted to modernist Marcel Breuer.

It must have been a challenge to create a monographic show on Rudolph, who was once the promise of architectural avant-garde and whose career in the 50s and 60s matched the monumentality of his buildings. But he fell out of grace, and suffered tremendously when unable to repeat the glory. His name comes up periodically for buildings that have been demolished despite calls to preserve them. Rudolph’s architecture is complex, largely misunderstood, and mostly unknown to the general public.

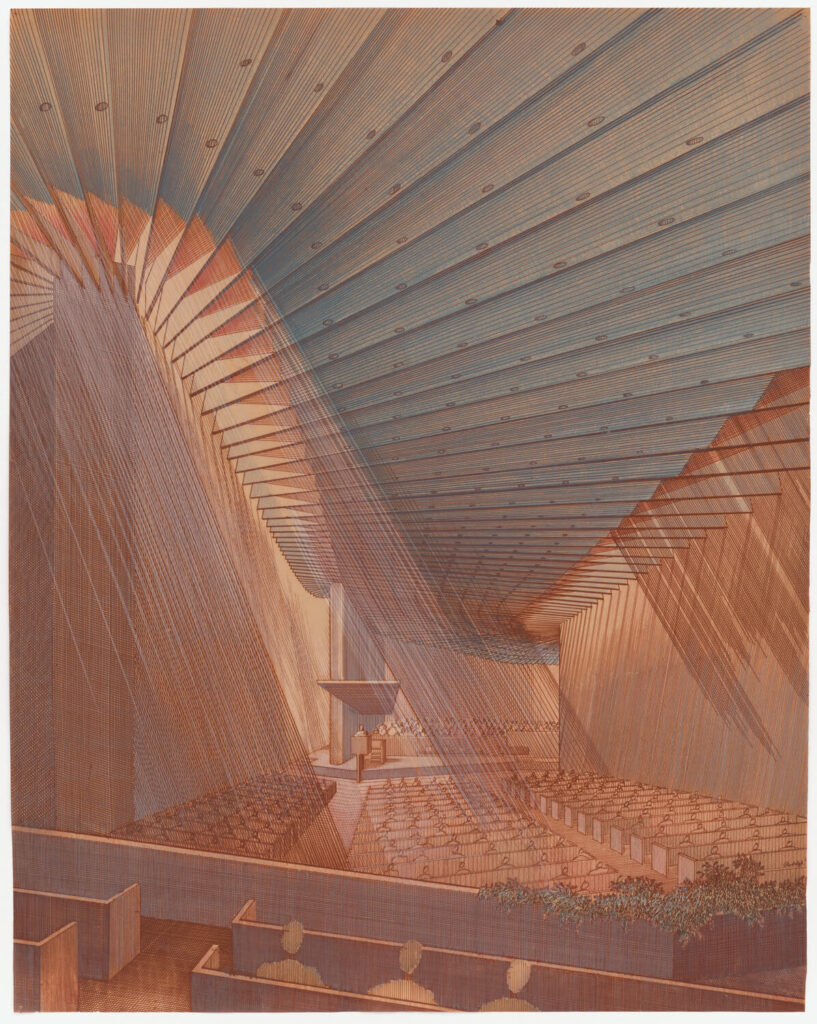

Paul Marvin Rudolph (1918-1997) was recognized for his exceptional talent from the very beginning. As a young architect in his early 20s, he built a couple of small modernist houses in Sarasota, which with their screens and shutters, came to address the local climate in a chic, innovative way. They were beach houses like never seen before and brought him his early fame. He then wen to Harvard Graduate Center, and as a student under legend Walter Gropius, was named one of three students seen as the promised future masters of the architecture world (the other two were Philip Johnson and Buckminster Fuller). He was always brilliant and visionary, creating elastic and complex spaces unlike anyone else. His architecture embodied the Space Age and when he created interiors in the 70s, they captured its glam, as they looked more like they belonged to dramatic movie sets or spaceships rather than functional living spaces. To summarize, his work brilliantly captured the spirit of the time.

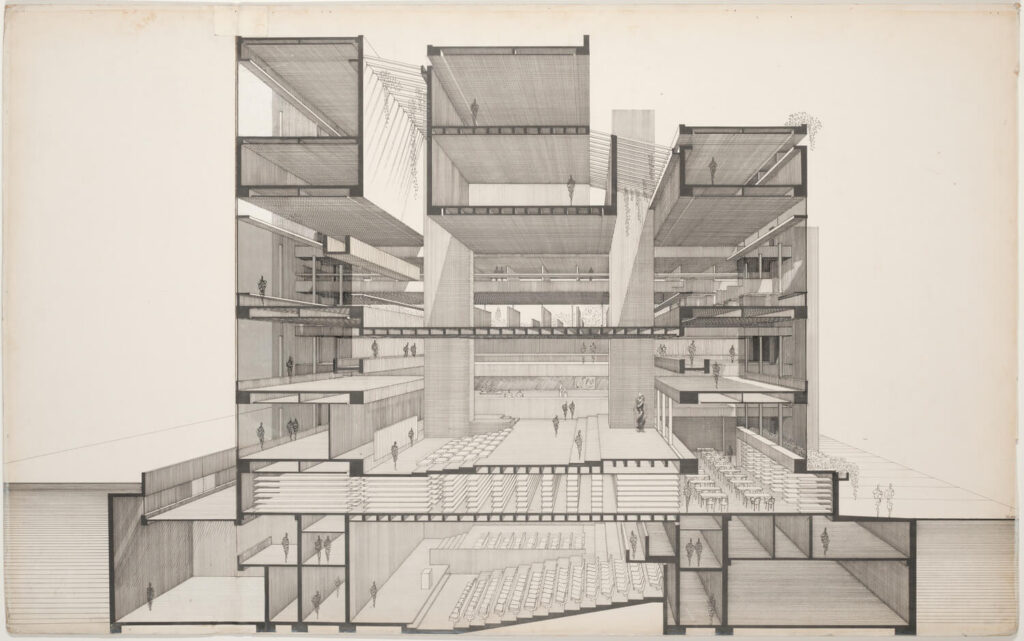

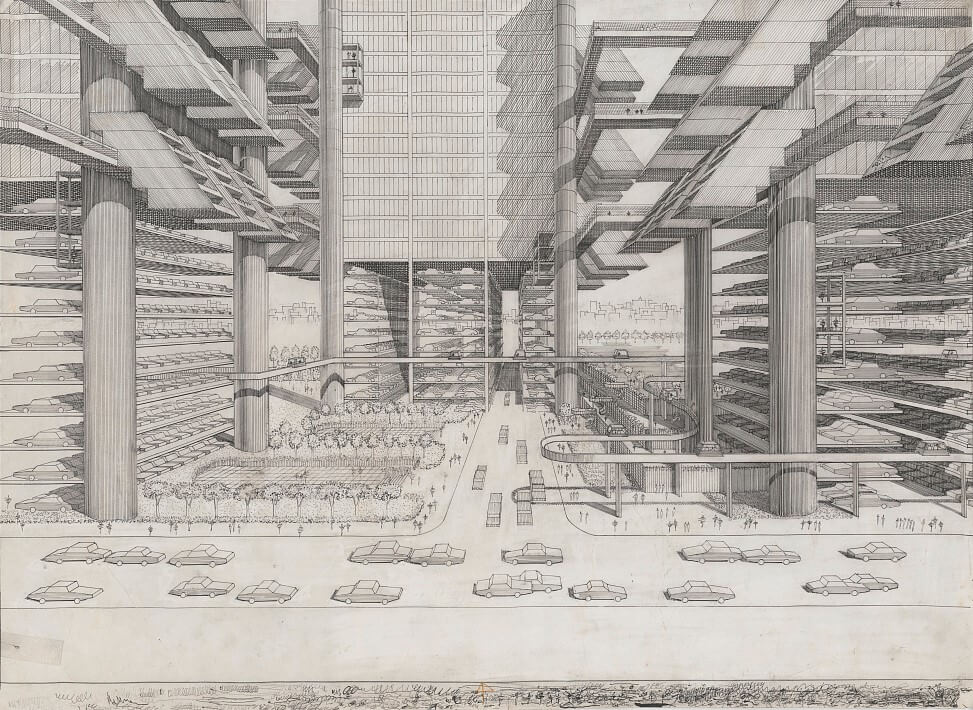

He was an American star of the mid-century and an educator who spent six years as the Chair of the Department of Architecture at Yale, for which he completed its controversial and at times infamous building, known today as Rudolph Hall. His monumental concrete buildings at universities and corporations and his urban renewal plans came to offer utopian ideas and push architecture to the future. Though he is often referred to as a Brutalist, his buildings were much more interesting, more textured and rough than those of the New Brutalist Movement. He was different than the otehrs and not only because he used precast concrete blocks rather than poured concrete.

With all of his spectacular persona and ambitious projects, something happened along the way, and Rudolph never made it to the Hall of Fame, never received the reputation he deserved, nor the acclaim of Eero Saarinen, Philip Johnson, or Louis Kahn. As his reputation declined, his grace was short-lived, amd despite inspiring Norman Foster and Richard Rogers, Rudolph has never become a household name and hardly knonw to the general public.

Why Rudolph? I had to ask Thomas. ‘I have always found his career a fascinating conundrum – his rapid ascent during the 1960s as a superstar,’ he told me. ‘And then his seeming disappearance from the mainstream architectural world, shifting to those extraordinary interior designs in the 1970s, before his “reemergence” in the 1980s with those important projects in East Asia.’ Thomas became fascinated with why there had never been a major exhibition before on such an important architect and by the fact that Rudolph’s drawings have rarely been on view. He perceived this chance to shine a light on this relatively under-studied architect – and to ‘finally bring out these stunning drawings for the first time to a major museum audience.’

When you walk through the Met’s exhibition, you feel as if Rudolph comes back to life, triumphing in front of your eyes, with all of his fame and splendor. His famed and vibrant drawings, which are usually seen in books rather than in their magnetic sizes, revealing the complicated floor plans (including the spectacular showpiece of the Bass Residence in Fort Worth, completed in 1972); the clips and films (including two films shot in Rudolph’s interiors — Brainstorm in the Burroughs-Wellcome Company Headquarters in North Carolina, and The Royal Tenenbaums, inside his own home); photographs of his monumental interiors, such as his own multistory penthouse on 23 Beekman Place with its Plexiglas bathtub; the numerous unbuilt projects and those which are no longer with us; the models of his megastructures; the urban projects; the space-age furniture which look as if they came out of Stanley Kubrick films; and finally, his personal art collection, all heroic and larger than life. It brought to my mind fictional avant-garde architect Edgar Krug, the hero of German expressionism who traveled the globe while constructing ambitious and futuristic buildings in colored glass, which came to change the world. Like him, to Rudolph, architecture was an agent of change.

Abraham Thomas’s companion illustrated catalog summarizes and clarifies the multifaceted career of Rudolph. As I read the reviews, I asked myself why some of the reviewers kept complaining about the lack of emphasis on Rudolph’s gay life. This aspect of his life has been overly discussed in the past, particularly by architectural historian Timothy M. Rohan, who over a decade ago elaborated on how Rudolph’s homosexuality was reflected in his work. But let’s not forget that he was discreet about his private life; why dig into something which was already explored? When I read those reviews, I am reminded of a podcast interview I had a couple of years ago about my late uncle, legendary music and opera critic Michael Ohad. The host insisted that I comment on his gay life, and I said that since this was not a part of the persona that he projected and the image that he constructed for himself, it is simply not important. My mom was quite proud of me. Why this terrific exhibition is critiqued on this basis, is unclear to me.

The exhibition is done well in covering all stages and aspects of Rudolph’s architecture, from the workshop, to residential, civic, universities, megastructures, interiors, and his projects in Asia. Just when it seems that the Met Museum is removing itself completely from design and architecture, this exhibition brings fresh life and hope for a brighter future.

To be honest, as I left the Met on a crisp autumn evening and walked along Fifth Avenue on a crispy autumn, enjoying its elegant, classical prewar buildings, I found myself thankful that the megastructures Rudolph proposed for New York City never realized.

Well done. Let’s meet at the house for a tour of Myron Goldfinger exhibition when you return from Paris.

Susan