Bouclé, a fabric made of looped yarn, has come to be synonymous with chic couture fashion of the 60s and 70s. So has Mohair. Few know that Bouclé and Mohair’s stories are tied to a series of historical and political shifts that have molded the life of their inventor. His name was Zika (Zikmund) Ascher, a master of those luxurious textiles, which were used by the best fashion houses in Europe—Christian Dior, Chanel, Balenciaga, Lanvin-Castillo, Pierre Cardin, Yves Saint Laurent, Alberto Fabiani, Ronald Paterson, Mary Quant, David Sassoon. Everyone in the forefront of the fashion world purchased their fabrics from Ascher’s showroom, but few knew that his fate was interwoven with Hitler’s National Socialist program.

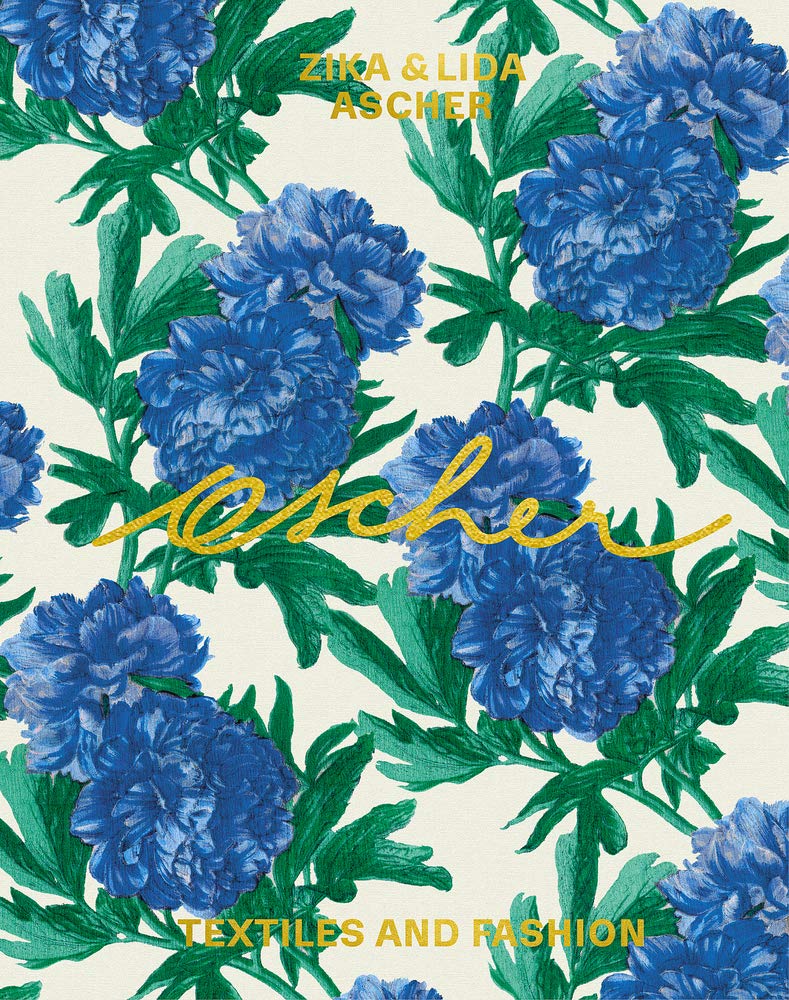

In fact, the life story of Ascher and his wife, Lida, captures the fate of those Jewish creatives who survived the Nazi’s malevolence. They were members of a generation that had to leave their lives, homes, and businesses behind, and flee overnight, never to see their homes again. Some of them, like Ascher, had to rise from the ashes of the War, a generation of Jews who moved to the world’s stage and succeeded in climbing to prominence despite the Nazi’s plan for the extermination of their people. A new exhibition that tells their story, ‘The Mad Silkman: Zika & Lida Ascher Textiles and Fashion,’ has opened at the gallery of New York’s Czech Center. It is a smaller version of an ambitious exhibition curated by Konstantina Hlaváčková at the Museum of Decorative Arts Prague, in 2019. Most of the material on display came from the archive held by Zika’s son Peter Ascher, who lives in New Hampshire.

Zika Ascher was born in Prague on April 3, 1910, to a Jewish family who had been in textile trades for generations. At 22, he opened a textile shop with his brother, Jindrich, which quickly became a success. Known as an expert Alpine skier, Ascher represented Czechoslovakia in international competitions, and was nicknamed “Mad Silkman” for his wild style on the slopes. His fiancée, Lida (Ludmila) Tydlitátová, was an active sportswoman, too. In 1938, Ascher was baptized at the request of his fiancée’s family and converted to Roman Catholicism. This would not help him, however, to escape the fate of the Jews of Czechoslovakia, because to him, everything changed when he married Lida in 1939. The two went to Scandinavia on a honeymoon, just a few days before the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia, and they were unable to return home. The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was quickly announced by Hitler, forbidding Jews to be engaged in trades.

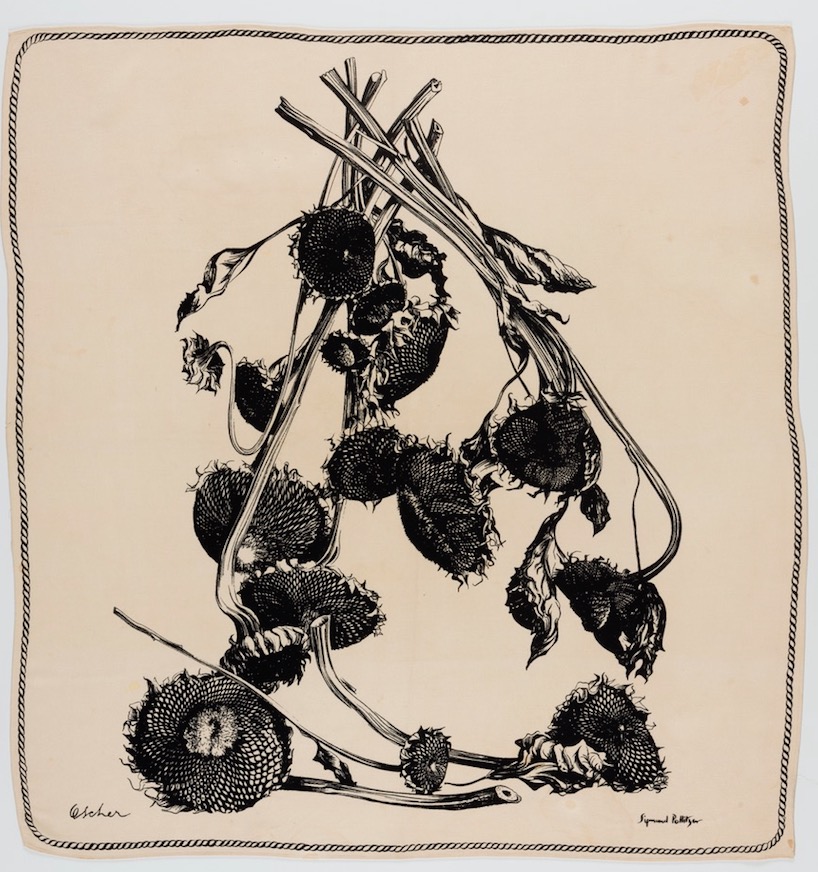

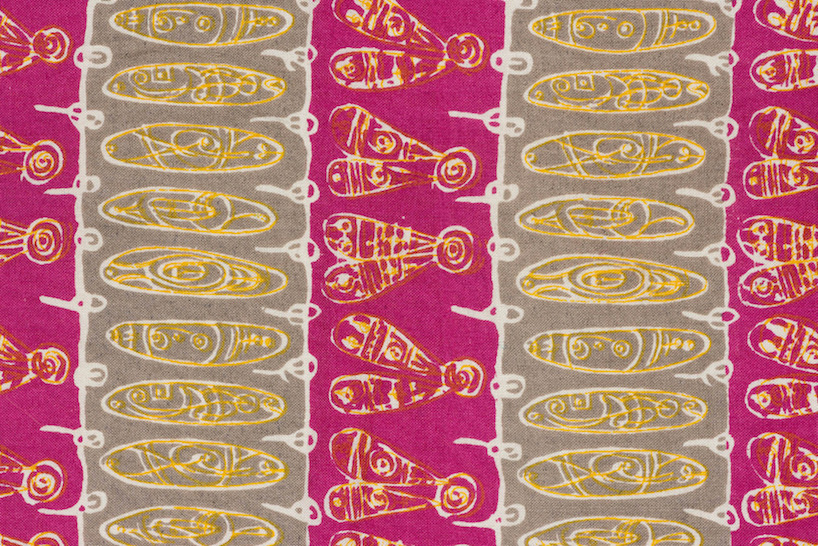

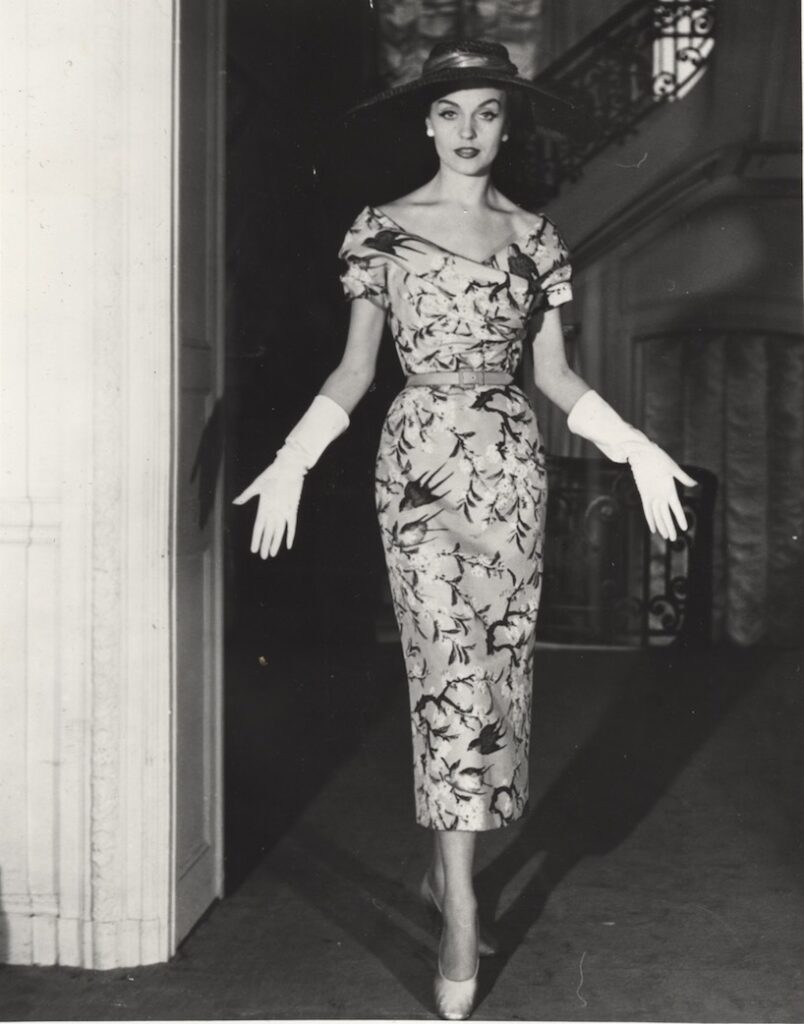

They emigrated to London, and in 1942 founded a textile company which first produced printed fabrics, and gradually other luxurious textiles for the fashion industry. The fabrics were crafted in the best workshops across Europe, particularly in Italy, and by the postwar years, the Aschers established their position as one of Britain’s best fabric makers. The famed flowered prints launched by Christian Dior in his New Look collection of 1947 came from their shop. The two invented an accessory that brought them global fame, when collaborating with world-renowned artists, including Henri Matisse, Henry Moore, André Derain, Cecil Beaton, and Alexander Calder to create patterns for scarves in silk crepe. They were called ‘Ascher Squares,’ and frequently appeared in fashion magazines. Each scarf was signed by the artist and identified by their recognizable styles. Calder created a scarf named La Mer with his typical organic structures; Pollitzer created his signature theme, Sunflower.

Textiles, I know, do not make blockbuster shows, but this one is a must because it demonstrates how world history is interwoven with this story. The monographic exhibition coincided with the publication “Mad Silkman: Textiles & Fashion” (Slovart Publishing, 2019). This publication is filled with original research, revealing the compelling story behind the textiles. All images © The Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague, Ondřej Kocourek, Ascher Archives.

Ascher Family Archive