Every design lover who frequents Milan would tell you that the city’s most magical spot—that place where the visitor (or local) can truly feel and breathe the beauty and elegance of old Milan—is Villa Necchi Campiglion on Via Mozart. This breathtaking house, built in the early 30s and opened to the public as a museum, provides a glimpse into the life and style of Milanese aristocracy during the interwar years. Recently brought to global attention when featured in the film House of Gucci, as the home of Rodolfo Gucci, this gem was designed by Milanese architect Piero Portaluppi (1888-1967) in the early 30s during the height of ‘Il Duce’ and Italian Fascism. In fact, the style, called Rationalism—a mitigated modernism—was adapted and advanced by the fascist regime. A new monograph dedicated to the architect, ‘Piero Portaluppi: Between Tradition and the Avant-garde,’ comes to shed light on this Milanese legend whose work has been completely ignored and his name omitted in books on design history, but which has a warm place in the heart of every Milanese who loves design.

Working over a period of five decades, we learn that Portaluppi brilliantly adapted to the Zeitgeist, and with his understanding of architectural styles and the political implication on building, he moved with the style of the day. He started his career in 1912 at the office of influential architect Ettore Conti who quickly became his father-in-law once he married his adopted daughter, Lia Baglia. It was Conti who introduced Portaluppi to Milan’s high society and to Edison, Europe’s powerful energy company, for whom he created numerous power plants. In the 20s, Portaluppi was appointed professor of architecture, and later became Dean of Architecture at Politecnico di Milano. In the 30s, he created his best work in both public and private sectors, when he moved to Rationalism. Although not fond of Mussolini, he took commissions from Il Duce during that decade.

My favorite chapter, titled ‘Milanese Itinerary,’ in which we discover Portaluppi’s masterpieces as we are led through the streets of Milan, one of my favorite cities in the world. I cannot wait to return and to follow the recommended path. Much of the work, we learn, is concentrated around the Piazza Duomo, Milan’s topographical center. Many of the locations featured in the book are open to the public.

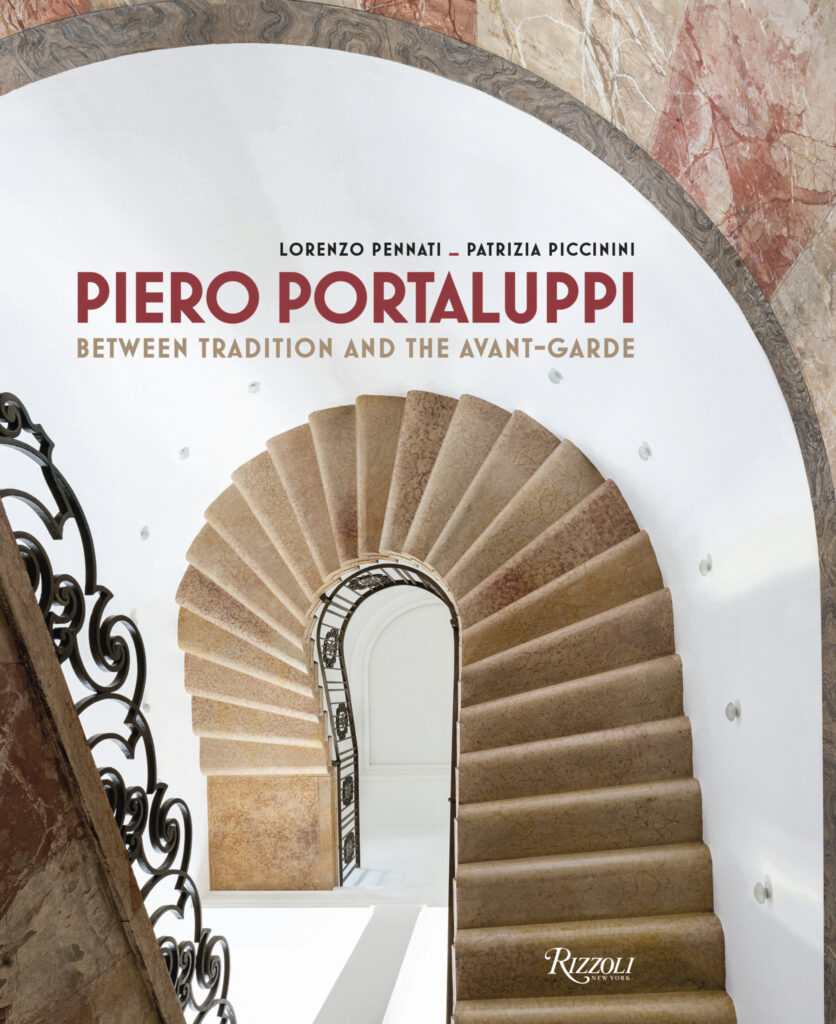

The book is beautifully illustrated with unpublished photography by Lorenzo Pennati, demonstrating Portaluppi’s contribution to Milan’s urban manifestation. His villas, offices, museums, are all rich in detail, revealing Portaluppi’s significance. He was the master of textures, trims, facades, and floors. His materiality and the way he used stone and tiles have become iconic to Milan. I wish the architecture analysis were more sophisticated, as in our discipline—design history and criticism—the identification of buildings between modernity and traditionalism is a bit scant and archaic. Modernism is much more than a break with the past, abstractions, reinforced-concrete, or stark compositions. This is the time to analyze Portaluppi’s work beyond the style-driven paradigm and perhaps to move it from the paradigm of traditional art history. Yet, this is an important book which should be added to every library.

It is hard to believe that an architect of his status, who built over 100 buildings between 1912 and the 60s, and who left his mark everywhere in Milan fell into obscurity and was virtually forgotten, until his legacy was rediscovered in the early years of the 21st century. This publication teaches us that there is still a great deal for architecture criticism and history to rediscover and illuminate.