A new gift book by Max Donnelly, Curator of Nineteenth-Century Furniture at the Victoria & Albert Museum, sheds light on the fascinating life and work of British designer Christopher Dresser. Why now? It is not clear, since the major retrospective of Dresser opened at the Museum in 2004, but it is nevertheless a compelling summary of Dresser’s scholarship, featuring the Museum’s extensive collection (and others, as well), all encapsulated in a small, beautiful volume, that has it all, entitled ‘Christopher Dresser: Design Pioneer,’ it was published last month by Thames & Hudson.

Christopher Dresser (1834-1904) is arguably the father of industrial design and one of the most intriguing figures in its long and distinguished history. This Victorian visionary was the first to work as an independent industrial designer, and among the earliest to understand the power of the Industrial Revolution to transform the look or products, long before this notion was promoted and practiced by the fathers of the Modern Movement in Germany. His peers were committed to new industrial processes, yet were not interested in departing from historical languages, constantly seeking to emulate the past and to prove that machines were no substitute for craftsmanship. Dresser was so far ahead of his time that he did not participate in that celebration, but rather befriended the reformers, who, like him, proposed radical solutions to modern life in the eve of the Victorian era. His more famous contemporary, William Morris, embraced the crafts as the only way to bring back value and dwelling culture to contemporary society. Although Dresser had respect for ornaments and tradition, he readily understood that the machine is the only way to revolutionize affordable consumer goods.

He was so “cutting edge” that when Japan first opened to the West, he was the first European designer to travel to Japan to learn firsthand the culture which began to penetrate to the West in the World’s Fairs of the 19th century. His journey to Japan was so inspiring that it came to completely reshape his oeuvre, turning him into the ultimate expert of Japan’s aesthetics. His visit was an official one, as Dresser was appointed by the British Government as an emissary to Japan, and his 2000-mile journey was recorded in his popular book, Japan, its Architecture, Art, and Art-Manufacturers: A Diary, which stimulated the birth of the so-called Anglo-Japanesque style in England.

The objects featured in the book demonstrate the amazing wealth of Dresser’s work and the multifaceted nature of his design. He did everything—furniture, textiles, carpets, and tableware—and his objects were produced in ceramics, glass, fiber, paper, and silver. He produced textiles and wallpaper with original ornament, but also objects where ornaments were completely absent. Yes, his most revolutionary, most modern, most radical work was metalwork. It shows that while Dresser was a true Victorian—his life spanned the reign of the famous queen—he had the courage to make a change in the conservative society, and for that he became successful against all odds. We learn that his taste was elevated beyond Victorian sensibilities.

The book provides an overlook on Dresser’s work, and it reveals some surprising, fresh information. I was amazed to discover that the only article on Dresser during his lifetime was published in The Studio magazine, in which he was descried as “the greatest of commercial designers imposing his fantasy and invention upon the ordinary output of British industry.” I have always been puzzled by the fact that Dresser became so successful despite the fact that his creations were so far removed from popular taste. The book does not answer this question. Today, his work looks as fresh as it did in the 19th century, and his taste resonates with our own. Thus, some of his work fetches astronomical prices in the international marketplace, and some of his designs are produced by Alessi. Whenever I post an image of one of Dresser’s metal pieces, my readers are astonished by the fact that he was a product of the Victorian age.

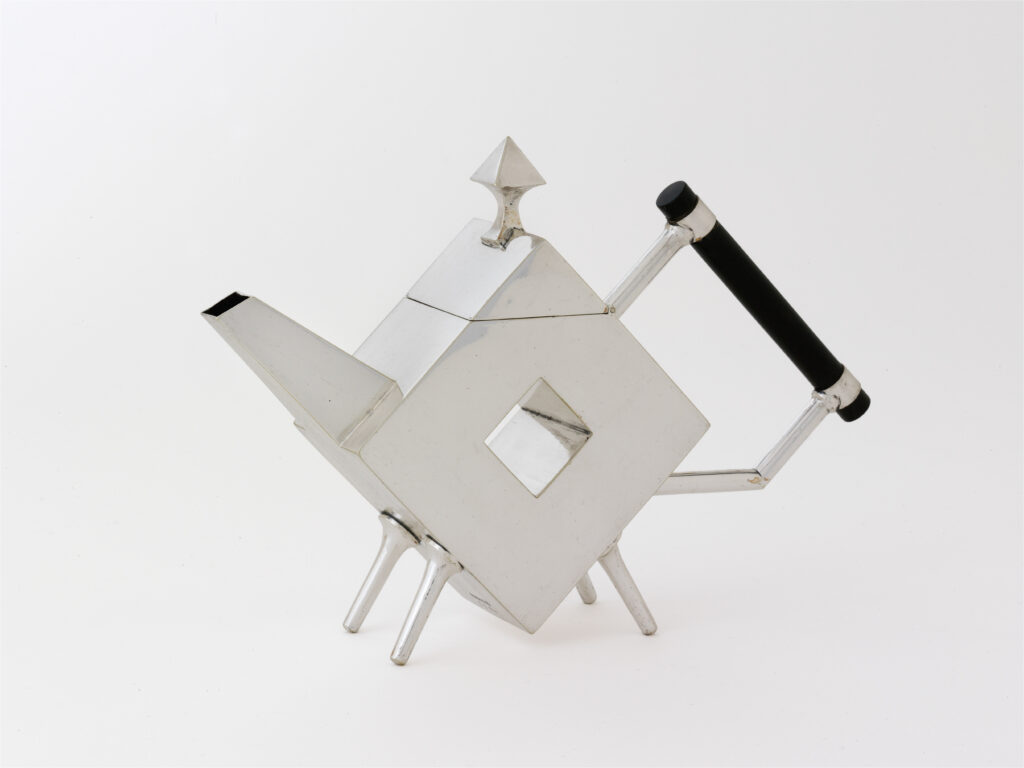

Above: Teapot, designed by Christopher Dresser and manufactured by Hukin & Heath, Birmingham. Design registered 6 May 1878; manufactured 1878–9. Silver, rush, enamel, ivory, lacquer, mother-of-pearl, carnelian. Text and photographs © 2021 Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Purchased with generous support of the National Heritage Memorial Fund, the Art Fund, the American Friends of the V&A and an anonymous donor, the Friends of the V&A, the J. Paul Getty Jr. Charitable Trust and a private consortium led by John S.M. Scott.

Birmingham and London. Design registered 26 March 1879. Glass and electroplated

nickel silver. Text and photographs © 2021 Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Pottery, Middlesbrough, North Yorkshire. Designed 1879–80; manufactured 1879–82.

Glazed earthenware. Text and photographs © 2021 Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Sheffield, South Yorkshire. Designed and manufactured c.1879. Electroplated nickel

silver and ebonized wood. Text and photographs © 2021 Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Purchased

with generous support of the National Heritage Memorial Fund, the Art Fund,

the American Friends of the V&A and an anonymous donor, the Friends of theCIS:M.4-2006

Glazed porcelain. Text and photographs © 2021 Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Glazed porcelain. Text and photographs © 2021 Victoria and Albert Museum, London