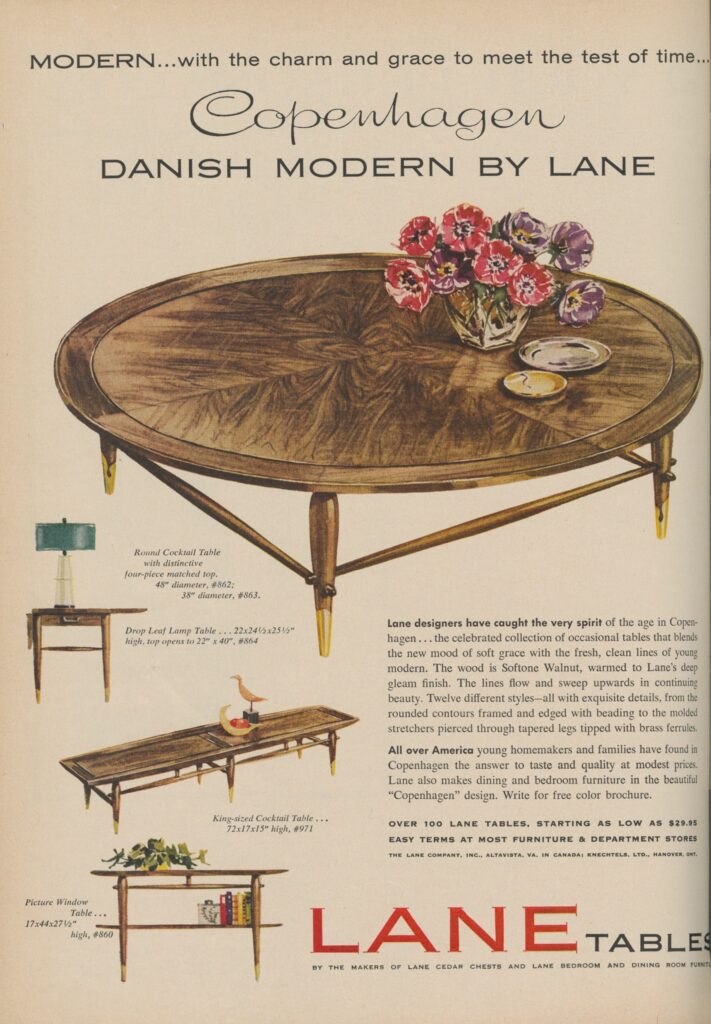

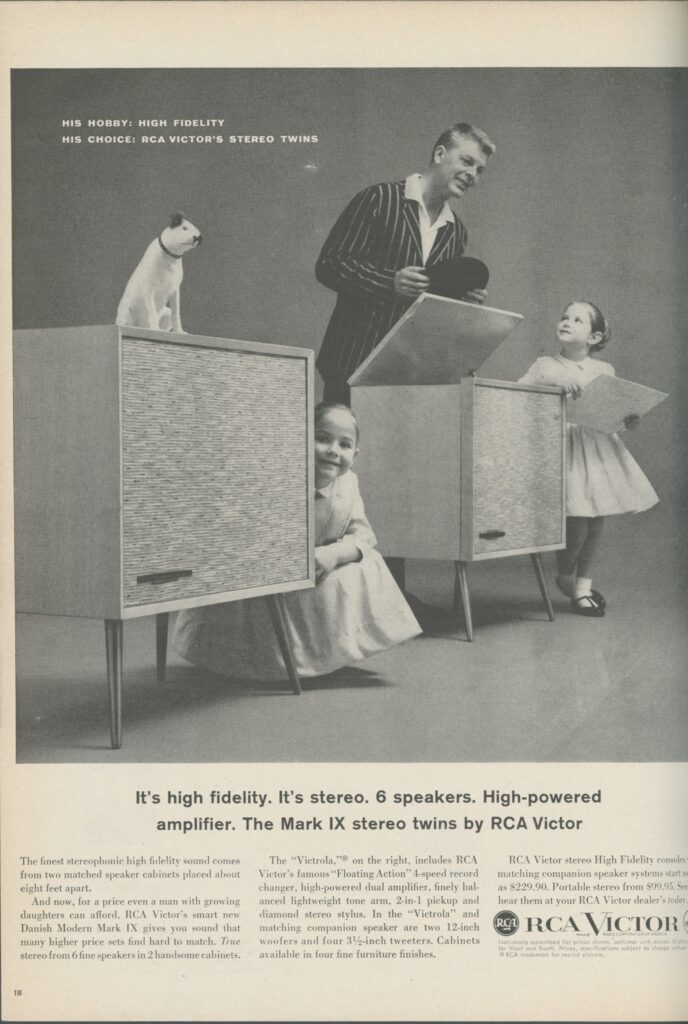

Danish furniture reached enormous popularity in the US during the height of modernism in the postwar years. It was widely loved for its light, elegant, chic look, as well as for its balance of proportions, youthful vibe, and harmonious integration of structure and wood. In those postwar decades, the Danish Modern—as it came to be known—burst on to the international market. It became a brand in its own right, sought after by young families living in the newly developed suburbs and urban apartments across the country. This trend swayed the taste of Americans away from the heavy, ornate antiques to modern.

Of all Danish chairs, several have reached the status of design icons, symbolizing the Scandinavian look in all of its allure. Two of them — The Round Chair by Hans Wegner, and the Chieftain Chair by Finn Juhl, both designed in 1949 have a lot i common. A new book by art historian Maggie Taft, The Chieftain and the Chair: The Rise of Danish Design in Postwar America, sheds a new light on the golden age of Danish Modern through examining those two iconic chairs. She tells the story of their conceptions, fabrications, and how they were marketed to American middleclass model homes and department stores, while touching on the political and cultural contexts that they were made in—the background of the creative and urban fabric of Copenhagen. In her book, she investigates the flood of copies across the market and examines the success it achieved as it was promoted by fabricators, designers, distributors, and the leading tastemakers of the day.

The two heroes in this book, the Chieftain Chair, and the Round Chair—nicknamed The Chair—both exquisite, innovative, timeless design masterpieces that were not made for mass production, but rather crafted by skilled cabinetmakers as showpieces. Both were introduced at the annual exhibition of the Copenhagen Cabinetmakers’ Guild Exhibition, Denmark’s a furniture show and competition that ran up until 1966, perceived as a vehicle for showcasing innovation and the emergence of the furniture movement. Yet, the two could not be more different. Each has its own personal aesthetics, demonstrating that the Danish look was not defined by a style, but rather by an approach, mode, and spirit. This fascinating book makes a great addition to the literature of modern design and the small scale of the book makes it possible to carry. Taft analyzes the chairs across the board. Since their inception, they have been recognized for their greatness. The Chieftain Chair was described in the New York Times as a “status chair,” and The Chair was famously featured in 1960 during the first televised US presidential debate between Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy, seen by the millions. Both candidates were seated on The Chair,described by Magazine Interior as “The most beautiful chair in the world.”

The Chieftain Chair looks more like a tribal throne than a Danish modern chair. I remember visiting Finn Juhl’s house last summer; the furniture designer lived in a suburb of Copenhagen, where he built his home 1942, just 7 years before designing his iconic chair. The Chieftain Chair stands in the living room of this small, humble house, which was planned according to the scale of mid-century residential homes. The oversized chair somehow works, and works well, as if it receives the legitimacy from the architecture itself to be defined as modern. While his peers sought to create furniture to conform to small apartments in the form of tiny pieces—folded down pieces from the wall, and multipurpose furniture—Juhl dared to push boundaries and created this statement piece. When a journalist suggested calling it “King’s Chair” after King Frederick IX who sat on it at the exhibition’s opening, Juhl instead chose a title that suggested a romantic and primitive authenticity. Wegner, on the other hand, created The Chair as a pure, simple, and organic form as a collaboration with cabinetmaker Johannes Hansen, who crafted this complicated structure in his tiny workshop.

We learn that Danish Modern’s rise in popularity was mainly due to the government perceiving design as a tool for commercial and industrial progress, similarly to the way Germany advanced design in the interwar period. The Danish look was cemented as the preferred look for the mid-century American home, and it achieved this status through the support of the local government and professional organizations who invested in strategies and development of export while also initiating exhibitions, showcases, and publicity through editorials.

Today, and in since 2000, mid-century Danish furniture has had a strong presence in the marketplace for 20th-century design, given a new identity in the world of curated interiors and advanced by a handful of galleries and auction houses which have developed and encouraged connoisseurship. It is hard to believe today that for the decades prior to the turn of the millennium, Danish furniture had lost its cache and relevance, pronounced to be dead and outdated. In the postwar years, Danish was perceived as clean, cool, and young, but since the early 2000s it has emerged as a player in the assembly of furniture in chic interior spaces, fitting in next to French midcentury, contemporary, and other varieties of easily recognizable 20th-century design masterpieces. While the book’s primary focus is Danish furniture, its ultimate benefit to the reader is the way it guides us to look at furniture; not simply as pieces that fulfill function, but as cultural treasures with a fascinating narrative.