Think about a world where every single house is furnished the same. Scary? This is what I had in mind when recently searching the web for furniture by Pierre Jeanneret. You can find it all: originals, knockoffs, re-editions, reproductions, fakes; made in India, Italy, the US; crafted and mass produced. The market is flooded.

Authorship, authenticity, collecting, and the notion of ‘good, democratic design’ as formulated by the founders of the Modern Movement were at the core of discussion this morning, when I hosted design editor and writer Sarah Medford in the opening session of the Spring edition of ‘Collecting Design: History, Collections, Highlights.‘ The ground was her excellent article ‘Is Your Jeanneret a Fake?,’ published in WSJ. in September 2019. We explored the state of the multifaceted market and the confusion, the cultural imagery, style identity, and level of taste attached today to the furniture, which Swiss architect Pierre Jeanneret created for the civic architecture project in Chandigah, India in the early 50s.

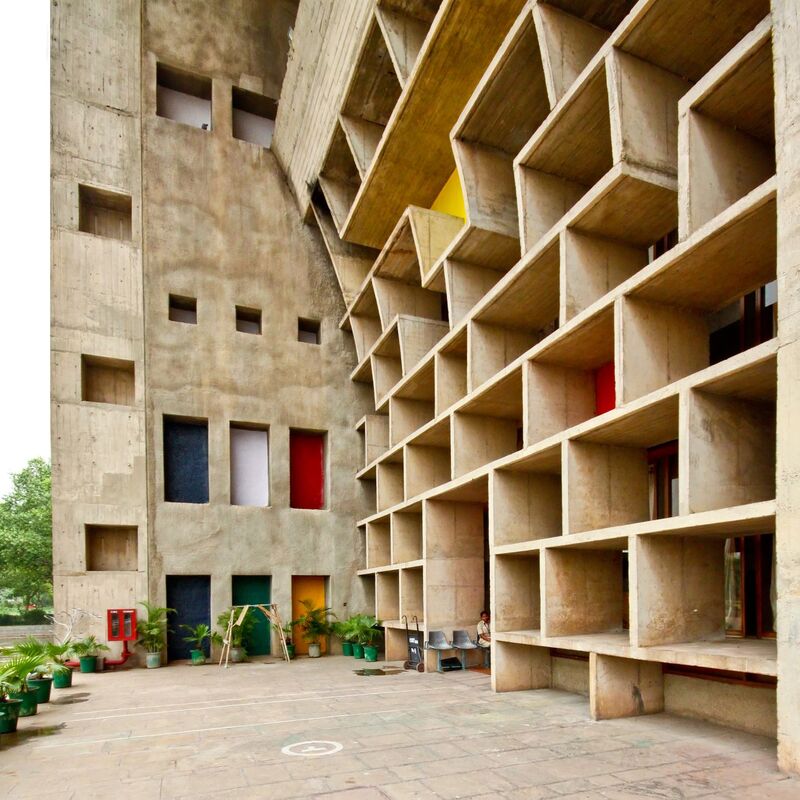

Let’s go back in time to a project hailed as the ultimate triumph of modernism, now Unesco World Heritage site. In 1947, on the eve of India’s independence, the British initiated a division between the Muslim and Hindu population, with Punjab assigned as the neutral state, dividing India and Pakistan. Since the former state capital city was now included in Pakistan, a new was initiated. Not just a capital, but as Jawaharlal Nehru, the first and Prime Minister of India envisioned, an ambitious masterpiece of modernity and progress. Le Corbusier was appointed to create the master plan which came to symbolize hope and optimism for the newly-independent state. The site architect was his cousin Pierre Jeanneret, who devoted nearly 13 years to the project.

While spending most of his career in the shadow of his famous cousin, the unprecedented market for Jeanneret’s furniture has recently brought the somewhat forgotten architect into the spotlight, a household name. Not for the work he did in advising the Indian government, nor for becoming mentor for the young generation of Indian modernists, but for the pieces he created to furnish the immense state and residential buildings: chairs, sofas, library tables, and dozens models, created in his office.

The furniture, which was rediscovered by three French dealers and one American collector and financier-turned design scholar in the early 90s, is the subject of Medford’s article. She became interested in the way this furniture has achieved an unparalleled popularity in recent years, in issues of authorship and authenticity, and in the legitimacy of new production of furniture which was initially made ‘for the people by the people’ in her words. In the most elegant and interesting way, Medford revealed the various aspects of the market illuminated in her research. The conversation moved from such leading tastemakers who live with rare originals, as French interior designer Joseph Dirand and Belgian fashion designer Raf Simons; to the French dealers Francois Laffanour and Patrick Seguin, who created the market and still rule it; to new production in India, America, and Italy. She has raised important questions on the line between the philosophy of creating affordable furniture for the masses and where this furniture is today, about notions of craftsmanship and local materials versus mass production and foreign materials, and what does it say about those whose imagination has been captured by this chapter in the history of design.

Thank you, Sarah Medford for contributing to the program Collecting Design and for a fascinating morning. All images of furniture in this post are courtesy Wright, included in Wright’s sale of authentic Chandigarh furniture in March, 2011, one of the most successful sale of this material, held in the US.

Authorship, authenticity, collecting, and the notion of ‘good, democratic design’ as formulated by the founders of the Modern Movement were at the core of discussion this morning, when I hosted design editor and writer Sarah Medford in the opening session of the Spring edition of ‘Collecting Design: History, Collections, Highlights.‘ The ground was her excellent article ‘Is Your Jeanneret a Fake?,’ published in WSJ. in September 2019. We explored the state of the multifaceted market and the confusion, the cultural imagery, style identity, and level of taste attached today to the furniture, which Swiss architect Pierre Jeanneret created for the civic architecture project in Chandigah, India in the early 50s.

Let’s go back in time to a project hailed as the ultimate triumph of modernism, now Unesco World Heritage site. In 1947, on the eve of India’s independence, the British initiated a division between the Muslim and Hindu population, with Punjab assigned as the neutral state, dividing India and Pakistan. Since the former state capital city was now included in Pakistan, a new was initiated. Not just a capital, but as Jawaharlal Nehru, the first and Prime Minister of India envisioned, an ambitious masterpiece of modernity and progress. Le Corbusier was appointed to create the master plan which came to symbolize hope and optimism for the newly-independent state. The site architect was his cousin Pierre Jeanneret, who devoted nearly 13 years to the project.

While spending most of his career in the shadow of his famous cousin, the unprecedented market for Jeanneret’s furniture has recently brought the somewhat forgotten architect into the spotlight, a household name. Not for the work he did in advising the Indian government, nor for becoming mentor for the young generation of Indian modernists, but for the pieces he created to furnish the immense state and residential buildings: chairs, sofas, library tables, and dozens models, created in his office.

The furniture, which was rediscovered by three French dealers and one American collector and financier-turned design scholar in the early 90s, is the subject of Medford’s article. She became interested in the way this furniture has achieved an unparalleled popularity in recent years, in issues of authorship and authenticity, and in the legitimacy of new production of furniture which was initially made ‘for the people by the people’ in her words. In the most elegant and interesting way, Medford revealed the various aspects of the market illuminated in her research. The conversation moved from such leading tastemakers who live with rare originals, as French interior designer Joseph Dirand and Belgian fashion designer Raf Simons; to the French dealers Francois Laffanour and Patrick Seguin, who created the market and still rule it; to new production in India, America, and Italy. She has raised important questions on the line between the philosophy of creating affordable furniture for the masses and where this furniture is today, about notions of craftsmanship and local materials versus mass production and foreign materials, and what does it say about those whose imagination has been captured by this chapter in the history of design.

Thank you, Sarah Medford for contributing to the program Collecting Design and for a fascinating morning. All images of furniture in this post are courtesy Wright, included in Wright’s sale of authentic Chandigarh furniture in March, 2011, one of the most successful sale of this material, held in the US.