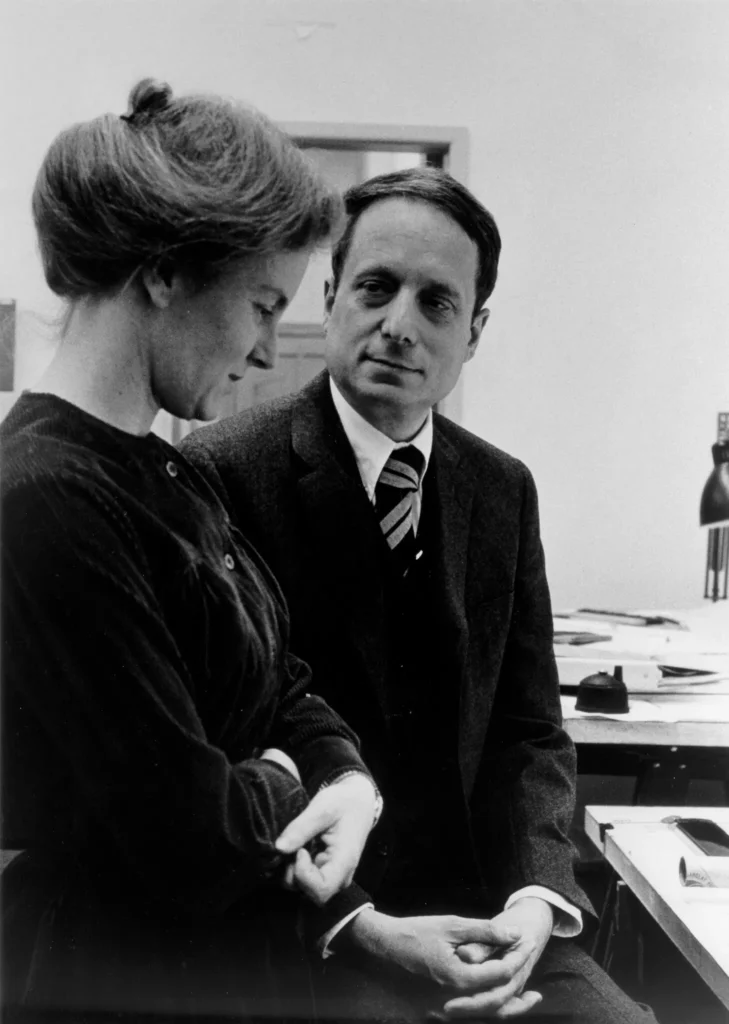

When Robert Venturi was 66 years old in 1991, he received the Pritzker Prize (known as the Nobel Prize of architecture). He was praised by the jury for merging art and architecture like no one before him, and his influential treatise, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1967), has been credited for diverting the mainstream of architecture away from modernism. Venturi and his wife and partner Denise Scott Brown have entered the pantheon of architecture history for revealing that ordinary things in American culture—rather than elitist and abstract ideas—should be praised and considered as the foundation for the new architecture movement of the 60s. But this text has taught us not only about that particular zeitgeist, but also about how to think of architecture and urbanism in a sophisticated, intellectual way, and how to look at architecture history.

Yet, Venturi and Scott Brown have remained enigmatic. Their texts have been mandatory in every architecture school across the globe, hailed as the most important sources for thinking of architectural postmodernism, and they have been admired by the architecture community as the heroes of 20th-century architecture. Despite this, their buildings have never made it on to the list of architecture icons, and they have never forged a personal recognizable style that is known to the general public. Their buildings are almost too intellectual to understand, and generally, they have not been referenced by the younger generation of architects since the turn of the millennium.

The New York edition of the ADFF (Architecture & Design Film Festival) opened last night with a screening of the new film, Stardust: The Story of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, on which their son Jim Venturi has been making for decades. It concluded with a talk between Venturi and architecture critic Martin Filler, moderated by Gabrille Esperdy. The film—named after the Stardust Resort and Casino in Las Vegas’ strip—comes to reveal the private story behind the lives and work of the powerhouse couple, whose mantra “Less is Bore” came to express the manifesto of Postmodernist design.

The film was made from archival material – lectures, tours, talks, personal footage — and footage shot by Jim Venturi for several years since he started to work on this documentary in 2004. It comes to illustrate the couple’s history from their childhood, the time they met, their enormous career, to near the ends of their lives. Venturi was raised by Italian parents; Scott Brown by a Jewish family in South Africa; both knew that they were going to be architects from early childhood. They married in 1967 in the most moving and stylish ceremony. In the film we see the powerful and energetic connection and the romantic relationship between the two, as well as the way they worked together hand-in-hand during the Pop era, changing the course of architecture history.

What charged their innovation was the recognition that popular culture and symbols of ordinary contemporary life were achieved through signs. Their theory was outlined in the book Learning From Las Vegas (1972), where they declared Las Vegas as the cradle of American pop culture. Not only Las Vegas, but the subway systems, Levittown suburban developments, and the mass-produced ranch houses built in postwar America. Venturi, we learn in the film, did for architecture what Andy Warhol did for art. Whereas Warhol looked at Campbelle’s Soup Cans and Billo boxes, Venturi looked at hamburger stands. Both artists (Venturi called himself ‘Artist’) were Americans who loved American culture, and both called for a change.

The film successfully brings us to the heart of the era with some of the best music. In the wedding scene of 1967, the Serge Gainsbourg and Jane Birkin’s Je t’aime is played as comparing to one of the most legendary love stories of that decade. When we watch how beautifully the film illustrates their magical connection, we are connected. To the people. However, the film also emphasizes how intellectual their theory was. The sexism of the era is revealed as Scott Brown, while an equal partner of the duo’s work, was mostly excluded from the constructed persona of her husband; not dissimilar to what Ray Eames experienced just a decade or two earlier.

The part which focuses on what is considered Venturi and Scott Brown’s most important building—the controversial 1991 addition to London’s National Gallery, the Sainsbury Wing—is particularly interesting and helpful to understanding their legacy. The footage of Prince Charles and Princess Diana as they unveiled the Foundation Stone for the Sainsbury and other footage such as that adds glam to the lives and work of the couple who could not stop holding hands. “I am an artist,” Venturi said, in a way stating his vision and purpose.

Tomorrow, the documentary will close the New York Festival.