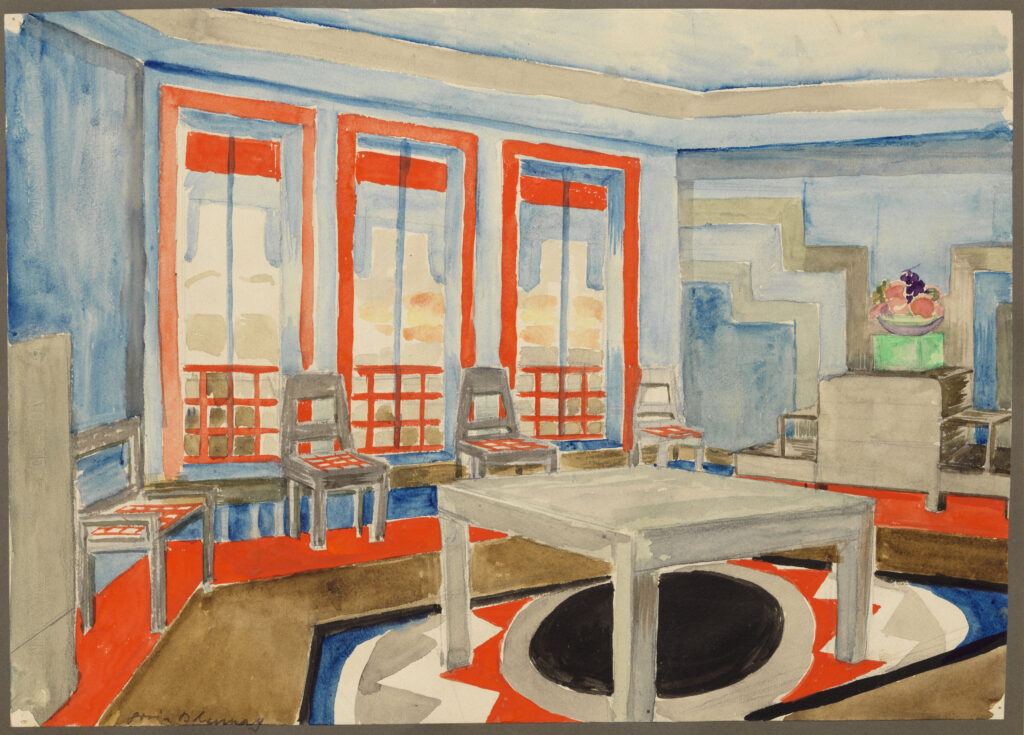

As soon as you enter the new exhibition Sonia Delaunay: Living Art, you know that you are about to have a magical experience. The most anticipated design show in New York City this season is being hosted at the Gallery of the Bard Graduate Center, my alma mater. This exhibition seeks to explore the life and work of one of the most successful and brilliant woman designers of her time considering her new discoveries, never-seen-before objects, and new scholarship. Delaunay (1885-1979) was an avant-gardist, influential and prolific in the ‘20s with her signature powerful abstraction and brightly colored patchwork patterns. She was widely recognizable in fashion and in everything she did: furniture, playing cards, fabrics, interiors, books, mosaics, and objects. This exquisite show gives much to look at and to learn from by taking us deep into the French avant-garde of the ‘20s and into the long life of one of the first artists to paint abstract in Paris, examining decade by decade against the world’s fairs.

While I always love coming back to the Bard Graduate Center where I received my PhD in 2006, it has been a while since it presented an exhibition of historical modern design, which was its a staple in its early years (the institution and its Gallery were founded in 1993), with the exception of Eillen Gray, which opened during pandemic. During those glory days my advisor—the late design historian Derek Ostergard—and the other curators presented one show after the other, all dedicated to new research in the decorative arts, design history, and material culture. Some of those shows emerged from classroom teaching and from faculty research. Situated in a New York mansion, the exhibitions always contained an extraction of great ideas and new discoveries, jeweled in the study of design history. Sonia Delaunay: Living Art seems like it brings back the glory of the gallery, and it was great to see.

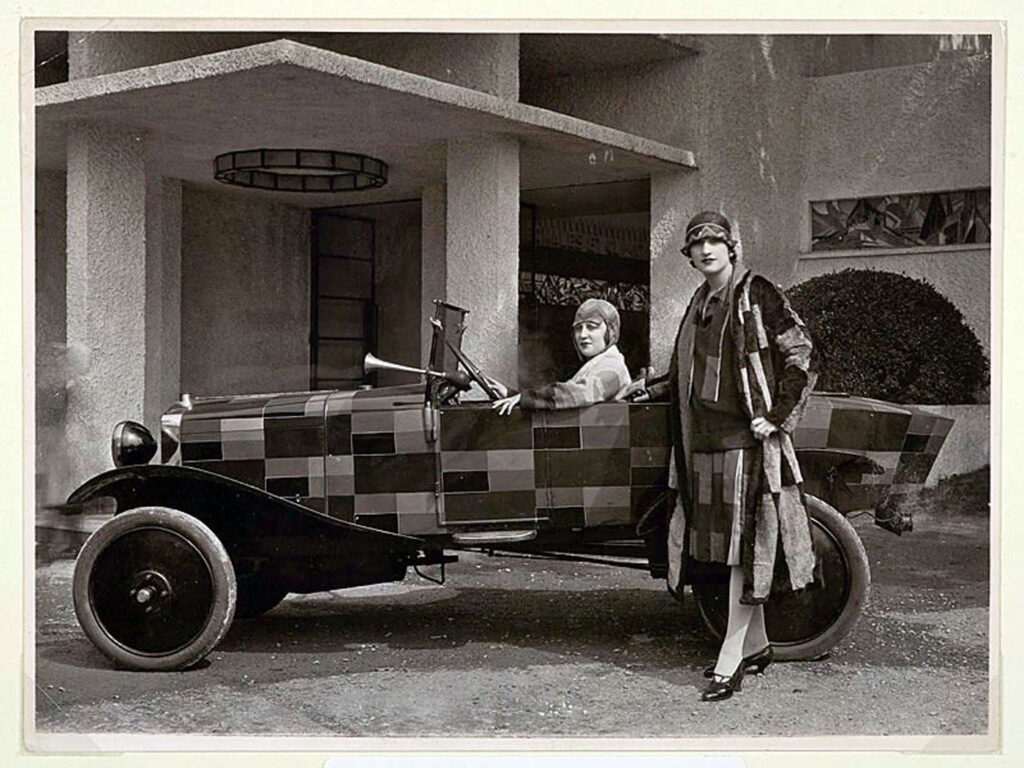

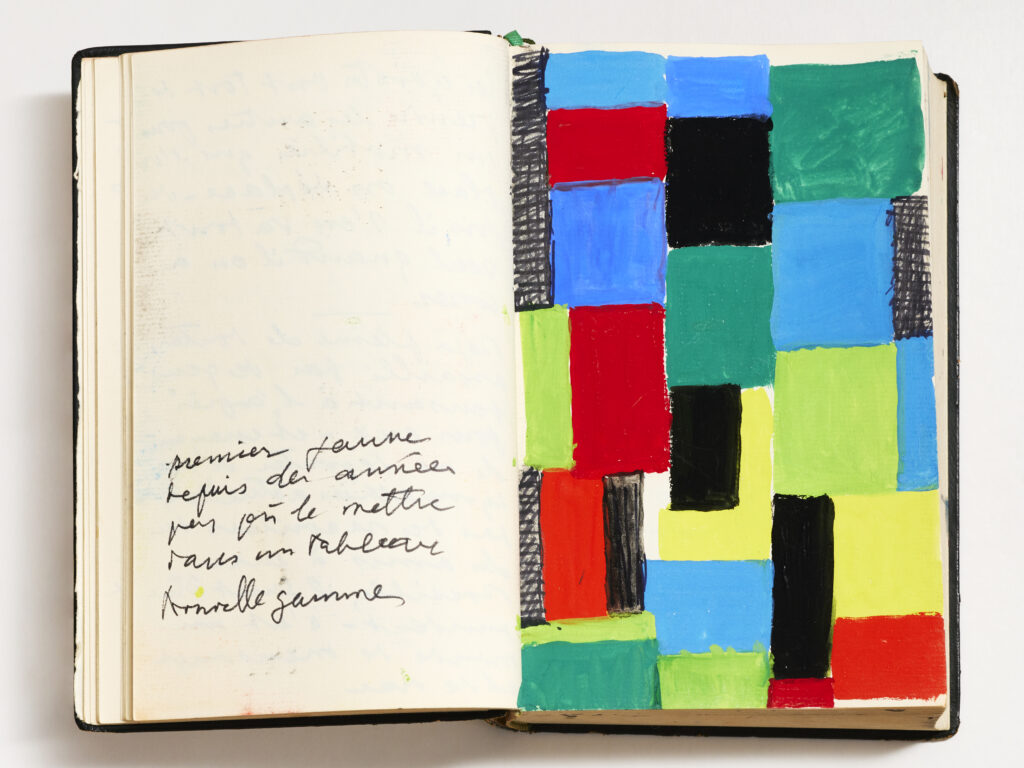

The survey show is comprised of hundreds of objects, all coming from major museums and private landers , which come to illustrate Delaunay’s long career from the 1910s through the 1970s. “Color,” she famously said, “is the skin of the world,” making colors central in her oeuvre. Experimenting with colors and the connection to new color theory was important to her. Despite this, the most famous and memorable image of her work is without a doubt a 1925 photograph in black and white; two models wearing her fur coats by a car painted after one of her fabrics, standing in front of the Pavilion du Tourisme by Robert Mallet-Stevens at the International Exposition of Modern Industrial and Decorative Arts, Paris, 1925.

Born in Ukraine in 1885, Sara Stern—as she was known to her working-class Jewish parents— moved to Paris at 21 years old where she met Picasso, Braque, and Robert Delaunay, who would eventually become her husband. The two forged a partnership in art and business, living in an apartment on Boulevard Malesherbes, which would be her home and shop. Together they were branded as pioneers. When the Nazis invaded Paris, they fled to the South of France where Robert died of cancer. She spent the next 38 years in Paris, remaining active well into the ‘70s, painting large canvases and creating mosaics. I loved the video of her meeting with Marc Bohan when he was the couturier for Christian Dior, and how he used her 1920s designs for his 1968 collection. She died at 94 and never stopped creating. The exhibtion will close on July 7th.

One of my favorite aspects about this exhibition is the design and graphics by Irma Boom, the most brilliant graphic designer in the world who has the ability to turn any visual into a powerful graphic experience. The exhibition will be open until July 7th.