Ever since Amy Siegel created her memorable video Provenance—which tells the curious story of a set of humble, yet exquisitely designed furniture made during the postwar years for the offices in the civic buildings of the new Indian capital of Chandigarh—this body of furniture has become a household product. Chandigarh was a city like no other; set at the foothills of Shivaliks, it was designed by Le Corbusier as a utopian modernist urban government compound. It was the pride of India’s first Prime Minister Sh. Jawahar Lal Nehru, with thousands of offices, High Court, University, and more. All of these official spaces were furnished with humble pieces of furniture crafted by local shops with local wood, designed by the architect and his cousin Pierre Jeanneret. As these started to be removed from India and brought to Europe and the US, they became collectible and tofday, seen everywhere. Vintage (and not so vintage) examples are regularly offered at auction houses across the globe, they are seen in chic interiors featured in magazines, while copies have flooded the market, and recent production by various furniture firms has been led by Cassina and RH, have made them popular and exposed.

There are many narratives and approaches attached to the story of the furniture, which was obscured for decades until rescued by a group of French design dealers 15 years ago. They have since come to symbolize not only social status and taste, but also the economic value and collectibility attached to objects of heritage. Office furniture used to be created by the thousands, were damaged from usage and often used as scrap wood, until being recognized, exported, and became a the ashion statement it is today. These stories have been told by players in the marketplace, and by the scholars Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret, who had signed off the design of hundreds of models crafted during the three decades of the building process of Chandigarh. What else can be said about this piece of material culture? What stories still need to be told?

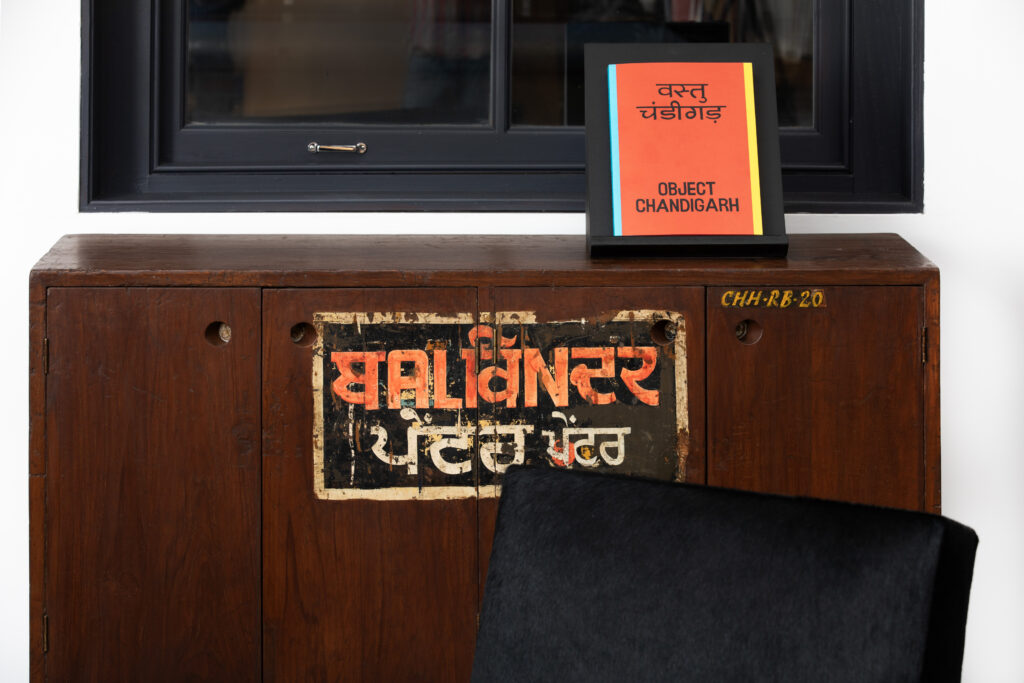

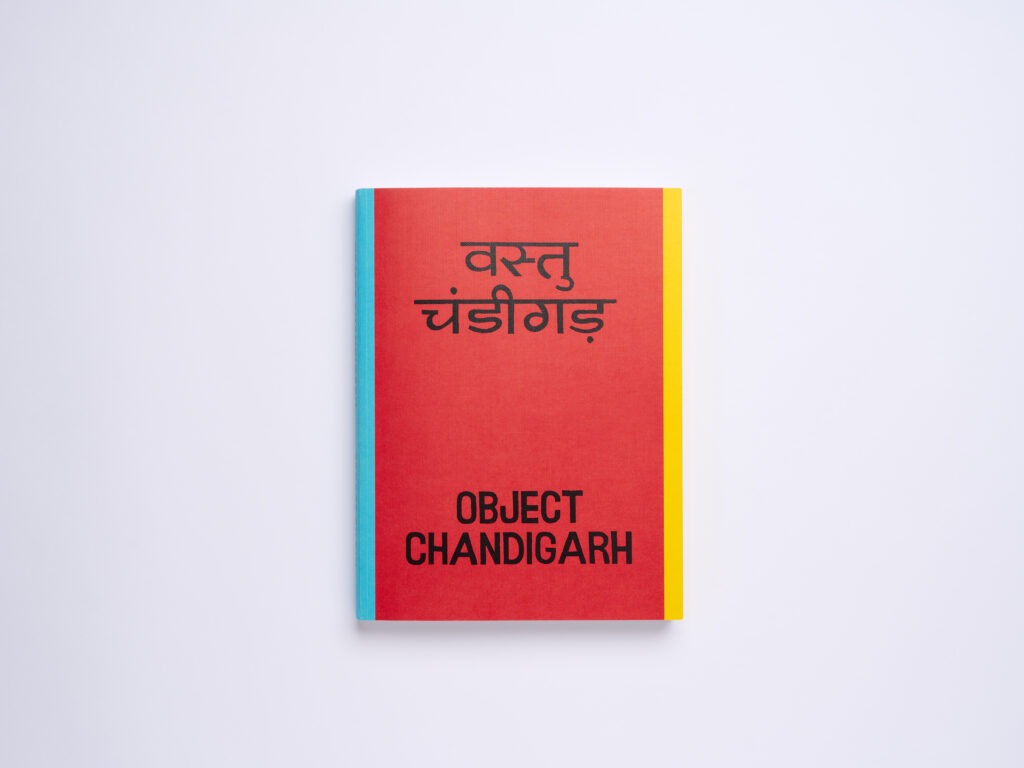

George Gilpin, a Brooklyn-based dealer who has been going to Chandigarh for years and is known for selling this furniture, is now telling his own story in his new book titled Object Chandigarh. The book was released in conjunction with an exhibition under the same title, which opened this week at Patrick Parrish Gallery and showcases models from his own personal collection. The limited-edition book is designed in the spirit of Le Corbusier’s polychromed architecture, since his love for color was legendary; he believed that color, particularly primary colors, play a significant role in evoking emotions and creating spatial illusions. Gilpin wants to tell the story of the furniture’s raw detail and the way it was found in India after years of use. It is a pictorial history with documentation of the furniture before it was restored and staged for contemporary interiors—what a difference. Since most people want their furniture to be beautiful, upholstered, and refinished, the pieces in their original state are hardly ever shown or photographed. The introductory essay by Simon Andrews, the trailblazer of vintage modern design, captures the complexity of the cultural and historical heritage of Chandigarh’s project. Both the book and exhibition teach an important lesson in design connoisseurship.

‘Once attuned to their aesthetic frequencies,’ Andrews says, ‘the poetic dialect of patina upon these objects reveals itself with fluency. These are furnishings that celebrate lived history with proud authority, as battered yet elegant warriors. Through their weary surfaces — with sun-bleached, split upholstery and improvised alterations — they announce an honest primitivism, honed by the souls of generations of users, travelling ever further from their modernist nativity. Their

emotive murmurs are essential, inimitable and valuable. They are imperfect, but all the more beautiful for their!jolie-

laide!honesty. These are objects that are repaired, but not yet restored. As if companion travellers to Orpheus,

they belong neither to one world nor another, fossilised, suspended within a memory of Utopia and not yet enhanced

to embrace the likely next.,’ capturing the allure of the authentic.

The exhibition will be open at Patrick Parrish Gallery through November 22nd.