As the design conversation has grown increasingly global, cross-disciplinary, and multifaceted over the last decade or two, I’ve puzzled over the limited attention paid by Western audiences—mainstream media, auction houses, and collectors—to the extraordinary production of Japan’s kogei tradition. Afterall, this body of contemporary handcrafted work, including weaving, ceramics, metalwork, and more, embodies the same values that are most highly celebrated in Western collectible design, from artistry and craftsmanship to innovation and sustainability.

This summer, I went to Japan on a journey of discovery, traversing rivers, forests, and mountains to reach the small towns where a number of intriguing and talented kogei artists live and work amid some of the country’s most historic and renowned craft regions. I visited Kanazawa, the mecca of lacquer art; Mino City, where the best washi paper has been crafted for 1,300 years; Bizen, where clay is fired with ash wood in enormous kilns; Beppu, where the bamboo weaving tradition goes back two millennia; and many other notable sites in between.

Hosted in enchanting homes, gardens, and studios, I got to spend hours with these artists, watching them throw clay, weave silk and bamboo, dye textiles in indigo, hammer silver, and inlay gold as I learned about their tremendous respect for heritage and their passion for preserving and perfecting their chosen crafts. Some honed their skills apprenticing with masters, while others were born into legendary families of makers. But all have devoted their lives—with astonishing energy—to transcending conventions to take kogei to new horizons.

Many of Japan’s kogei artists trace their philosophy to mingei, a movement that emerged in the 1920s in celebration of handcrafted, anonymously produced everyday objects. In mingei, beauty was found in the useful, and making was practiced with a kind of spiritual devotion. Today, leading kogei artists often approach functionality as a point of departure to achieve highly expressive, sculptural, even dramatic works that magnify the expansive potential of their media. With courage and vision—fueled by Zen philosophy, an abundance of creativity, and exquisite technical knowledge—they are wielding their practices as agents of transformation and elevating handcraft to the status of fine art.

In three parts, I am recounting my unforgettable experiences visiting the studios of 18 kogei artists. Part I focuses on three who trained in Beppu to work in bamboo.

Bamboo is magical. Beyond its inherent beauty, this material—part of the grass family—can be woven into almost any shape. Rapidly growing and self regenerating (without the need for fertilizers or pesticides), it is among the most sustainable materials on earth. In Japanese culture, bamboo has long occupied a fundamental place, used to make furniture, screens, lanterns, chopsticks, kitchen utensils, all manner of utilitarian and decorative baskets, and even architecture.

In recent years, a new generation of artists has brought a fresh perspective to bamboo weaving, mastering and evolving ancient skills to achieve new heights of personal and artistic expression. They engage all phases of the production process, including harvesting, cutting, and preparing the bamboo for weaving.

To see the best bamboo kogei, I traveled to Beppu, a hilly city famous for bamboo and hot springs, located on the southern island of Kyūshū. Here, centuries-old methods of bamboo weaving have been fully preserved, and, with the support of Beppu City Craft Institute, the region has become a hub for state-of-the-art bamboo research. Beppu is also home to the country’s only educational facility dedicated to bamboo craft; originally founded in the early 20th century, it operates now under the name Oita Prefecture Wounded Warrior Vocational Re-education Institute. It is the alma mater of Japan’s most accomplished bamboo artists (including the three I visited on my journey). Only 12 students are accepted per year, and the complex training requires two years—the first devoted to foundational skills, and the second devoted to personal mastery and individualized expressions. Off premises, students are mentored by eight professional bamboo craftspeople.

Yonezawa Jirō (b. Kyūshū Island, 1956)

Award-winning Yonezawa Jirō studied bamboo basketmaking at the Beppu Vocational Arts Training Center; he graduated 42 years ago. A native of Kyūshū, he has been surrounded by bamboo his entire life, but he didn’t dedicate himself to the craft until he was 22 years old. Even so, his identity as an artist reflects his deep relationship with the region’s bamboo-filled landscape. He takes great pride in selectively harvesting his material to ensure the long-term health of the groves.

Unlike other Japanese bamboo artists, Jirō lived in Portland, Oregon, for 18 years, which enabled him to bring a new context to his work. He drew inspiration from encounters with the work of American fiber artists, such as Kay Sekimachi, John McQueen, and Gyongy Laky, as well as traditional Native American basketry. In Portland, Jirō began to distance himself from the traditional techniques he learned in Japan. He developed a distinct, sculptural language through an unconventional, labor-intensive way of cutting bamboo into wide strips as well as a unique approach to braiding and dying. As he was demonstrating for me the preparation of the bamboo strips in his studio, I noticed how meditative the process seems to be for him.

Award-winning Yonezawa Jirō studied bamboo basketmaking at the Beppu Vocational Arts Training Center; he graduated 42 years ago. A native of Kyūshū, he has been surrounded by bamboo his entire life, but he didn’t dedicate himself to the craft until he was 22 years old. Even so, his identity as an artist reflects his deep relationship with the region’s bamboo-filled landscape. He takes great pride in selectively harvesting his material to ensure the long-term health of the groves. Unlike other Japanese bamboo artists, Jirō lived in Portland, Oregon, for 18 years, which enabled him to bring a new context to his work. He drew inspiration from encounters with the work of American fiber artists, such as Kay Sekimachi, John McQueen, and Gyongy Laky, as well as traditional Native American basketry.

In Portland, Jirō began to distance himself from the traditional techniques he learned in Japan. He developed a distinct, sculptural language through an unconventional, labor-intensive way of cutting bamboo into wide strips as well as a unique approach to braiding and dying. As he was demonstrating for me the preparation of the bamboo strips in his studio, I noticed how meditative the process seems to be for him.

Jirō returned to Japan in 2008 to care for his elderly mother and reconnect with his roots. He built his studio on his family’s compound and turned his family home into a showroom. He joined the national associations and began to participate in national exhibitions. He has become known for work that has an undeniable charisma—bold, balanced, colorful, and abstract. As Philippe Boudin, Director of the Mingei Arts Gallery in Paris, told me, “Jirō has projected his work into the art world of the 21st century without denying the tradition that is the source of his artistic soul.”

Osamu Yokoyama (b. Matsumoto, 1980)

Osamu Yokoyama was not born in bamboo territory. In fact, he took up the craft as a second career, following a revelation around age 30 that his first profession—graphic design—was not his true passion. He wanted to create things by hand. Soon after, he moved his young family from Tokyo to Beppu and enrolled in the bamboo craft training center. There he met his mentor, bamboo artist Jin Morigami, and quickly recognized the artistic potential of this natural material.

After a year of learning basic technical skills, Yokoyama’s second year at school, he recalls, brought another revelation: that the more he tried to follow the rules and stay loyal to fundamental principles, the more he lost touch with craft’s true potential as well as his own expressive voice. He began to ask questions, seeking to connect with his inner creativity. By the time he finished his graduation project, he had established the seeds of a fresh and independent vision. When his work was eventually shown by Wahei Aoyama, founder of the Tokyo-based gallery A Lighthouse called Kanata, he began to attract a wide audience of admirers. Today, his innovative, free-standing sculptures—forms that shouldn’t be possible in the medium of bamboo—sell out before his exhibitions even open.

“It is not bamboo craft techniques that I am trying to express,” Yokoyama explains. “Rather, [I want to] express the nature of the bamboo itself through the techniques.” He has discovered that his true passion is using his own voice and approach “to always be neutral and unbiased when trying to find the answers to the fundamental questions of bamboo.” Yokoyama’s love for bamboo and its spiritual aspect is apparent. “When using this material as a means for expression,” he says, “the work must express something that goes beyond its natural beauty.” He adds: “But pursuing the deeper beauty of bamboo is not an easy path.”

Tanabe Chikuunsai IV (b. Sakai, 1973)

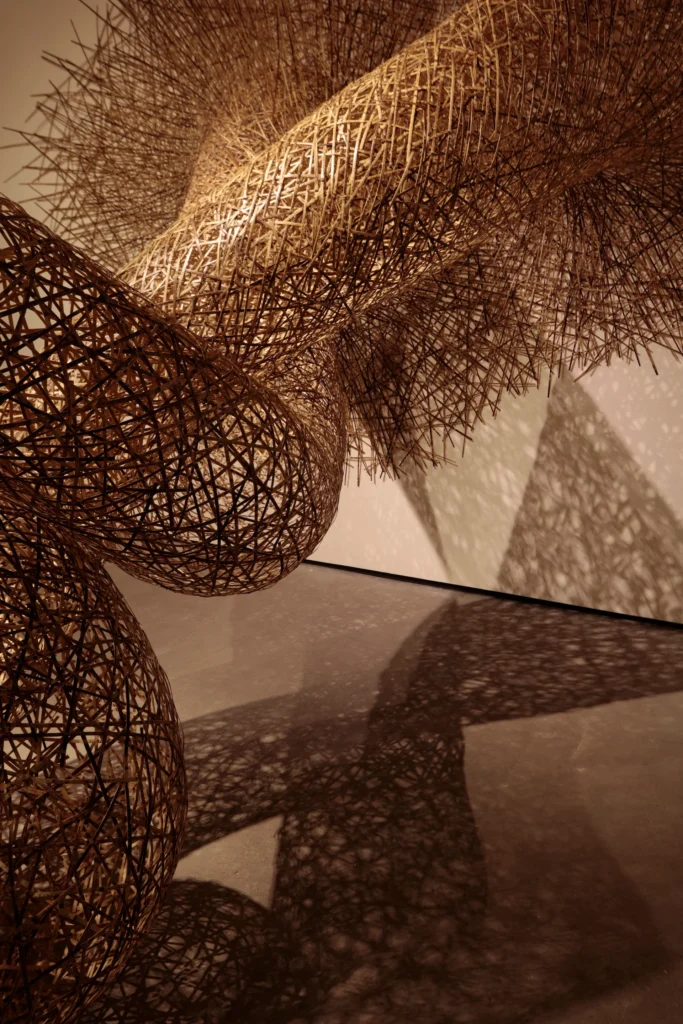

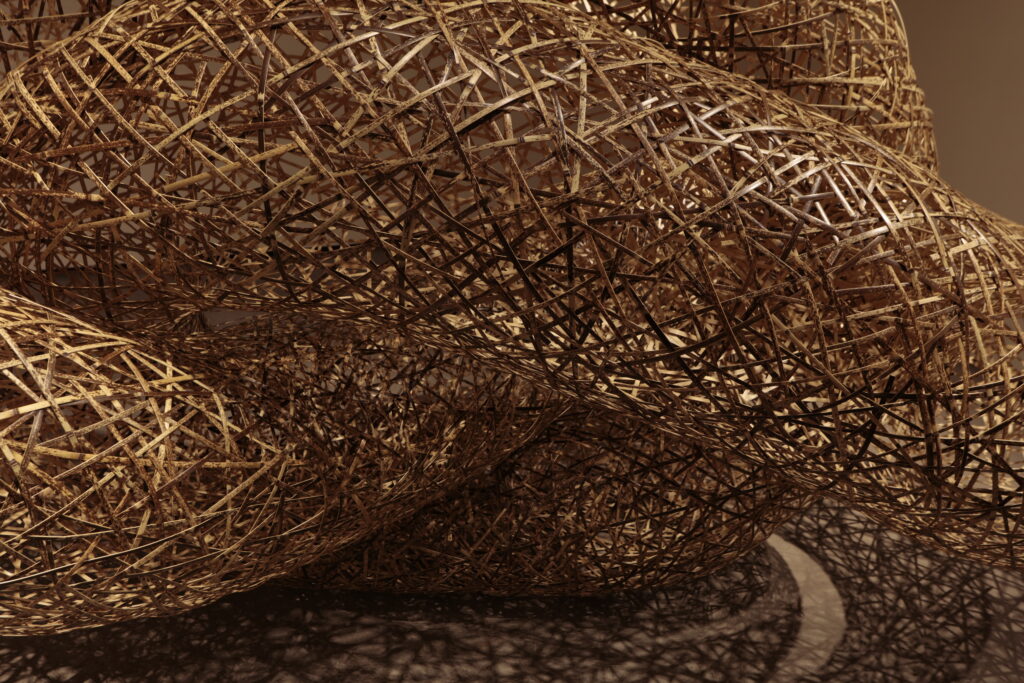

Like no one else, Tanabe Chikuunsai IV has taken the craft of bamboo weaving into the realm of monumental contemporary art installation. Along the way, he has brought bamboo art to a global audience.

The fourth generation of a prolific bamboo weaving family, Chikuunsai IV has an impressive pedigree. He began weaving as a child. After graduating from Tokyo University of Arts, he went to Beppu to study basketmaking before returning to his family home near Osaka, where he continues to live today with his widowed mother, wife, and three teenagers—the next generation of bamboo artists to whom he is passing his masterful skills.

While his father, Tanabe Chikuunsai III, and mother both produced sculptural works during their careers, Chikuunsai IV pushed the envelope further by applying traditional weaving techniques to the creation of monumental, landscape installations made of thin strips of bamboo. His works have a nobility. Often reminiscent of bamboo forests, they invite the viewer to walk inside and around, highlighting the essential relationship between humans and nature.

Chikuunsai IV’s intricate, site-specific sculptures have been commissioned by a number of important international institutions, such as New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, Paris’ Museé Guimet, and Geneva’s Baur Foundation, as well by high-profile brands like Gucci and Takashimaya. He has played a crucial role in elevating not only the art of bamboo but also the science. In his quest to expand the possibilities of the material, he has collaborated with Sawako Kaijima, a computational specialist and Assistant Professor at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, using software and 3D-printed molds to design mathematically complex structures that he then realizes in bamboo.

Chikuunsai IV’s intricate, site-specific sculptures have been commissioned by a number of important international institutions, such as New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, Paris’ Museé Guimet, and Geneva’s Baur Foundation, as well by high-profile brands like Gucci and Takashimaya. He has played a crucial role in elevating not only the art of bamboo but also the science. In his quest to expand the possibilities of the material, he has collaborated with Sawako Kaijima, a computational specialist and Assistant Professor at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, using software and 3D-printed molds to design mathematically complex structures that he then realizes in bamboo.

This article was published today in The Forum by Design Miami/.

I would like to thank those whose efforts made this tour and published article possible: Wahei Aoyama and Kumiko Sunahara of A Lighthouse called Kanata; Margo Thoma of TAI Modern; Tom Grotta and Rhonda Brown of browngrotta arts; Galerie Mingei Japanese Arts; and the three artists Yonezawa Jirō, Osamu Yokoyama, and Tanabe Chikuunsai IV. Stayed tuned for Part II of the Celebrating Kogei editorial series, coming soon.