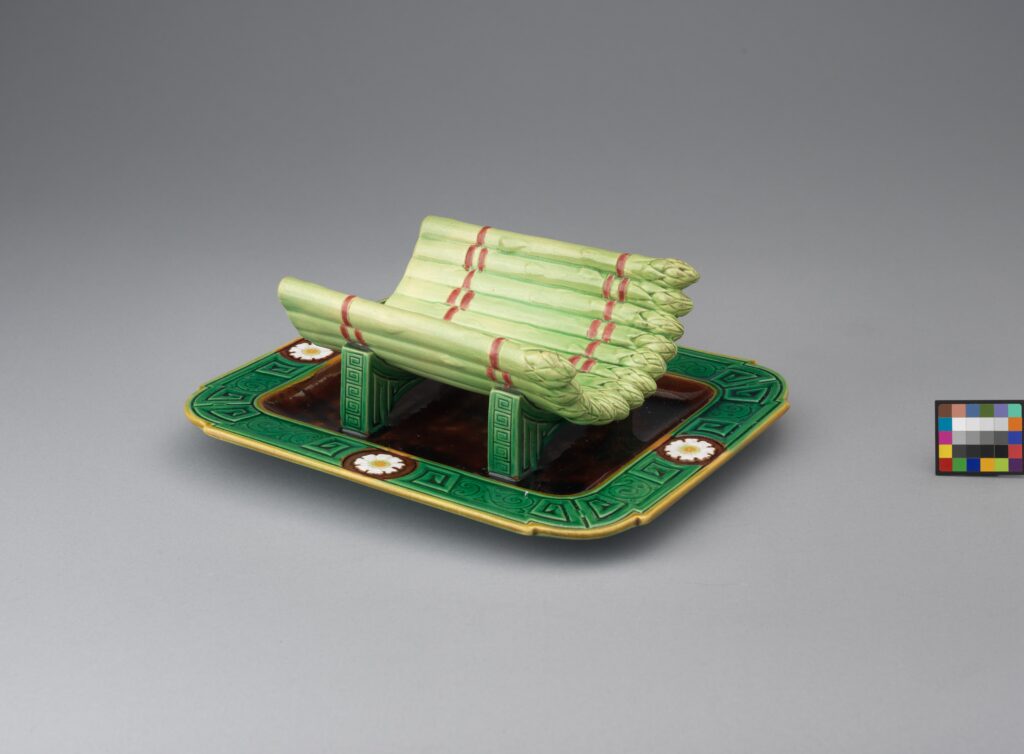

Last week, I visited the exhibition Majolica Mania: Transatlantic Pottery in England and the United States, 1850–1915 at the museum of my alma mater, the Bard Graduate Center. Although my taste is minimalist, tending toward modernism and craftsmanship, from the moment I started my studies in the history of decorative arts, I fell in love with the maximalist, industrially produced Majolica. I am not referring to what you’ll find in today’s museums—the Italian Renaissance tin-glazed pottery collected by the Italian nobility, which reached its artistic height in the 16th century. I refer instead to the highly decorative, whimsical, and vibrant Victorian-molded earthenware, named after the Italian precedent. Serving pieces, tableware, sculptures, and garden furniture, were all utilized by millions in England and the US until WWII. Majolica was perceived by Victorians as an expression of the triumph of industrialization and the new technology it engendered, a testimony to the power of the industrial revolution to transform the taste of the growing middle class, providing them the opportunity to live in high style.

When I attended the master program in the history of decorative arts in the early 90s, the study of 19th-century material culture was at its height, and Majolica was enjoying a revival. Some companies produced majolica-style dinnerware which was used in many American and British households. But in the past twenty years, with the exception of antique shows and one serious association of collectors devoted to the form, Majolica has been completely disregarded. The taste for mid-century modern and the desire for pared-down homes has pushed the exuberant glazed ware to the attic, where it quickly became associated with Victorian kitsch. I was therefore thrilled to hear that the Bard Graduate Center had opened an ambitious exhibition—the largest in its history—devoted to Majolica, accompanied by a three-volume catalogue, illuminating an entire culture that has disappeared from the world: the interiors, as well as the dinner and garden culture.

The secret to loving majolica rests with the display. It is only when you see it in quantities, in its many varieties, when you see in front of your eyes shelves filled with colorful teapots, dishes, jugs, that you can really get a full sense of its grand allure. And this is exactly what this exhibition does. It presents Majolica in overwhelming quantities, and not only as a metaphor to its mass production. The show presents the numerous aspects related to majolica—the makers, the collectors, the full scope of its forms and patterns, demonstration of the techniques and production, and the consumer culture that enabled Majolica’s existence, bringing to life the lifestyle of 19th-century middle class and Victorian domestic culture.

At the center of the show, the renowned English firm, Minton & Co, can be credited with inventing Majolica and which was in business well into the 1990s. But when England opened the Great Exhibition of 1851—the first World’s Fair, showcasing the achievement of the industrial revolution—it was Minton which exhibited the polychrome majolica for the first time.

The private tour I attended was led by the two curators of the show, Laura Microulis and Earl Martin, who told us about the research behind this exhibit. I was surprised to learn that many of the pieces included were, in fact, purchased for the show and for the museum’s study collection. Eccentric Victorian Majolica with its vibrant, colorful, bold, and glossy appearance, provides a refreshing way to experience design. All images courtesy The Bard Graduate Center.

Wonderful. I love it too. That bunny tureen!

Hope you’re well.

Nancy

Nice piece on Joseph in the FT