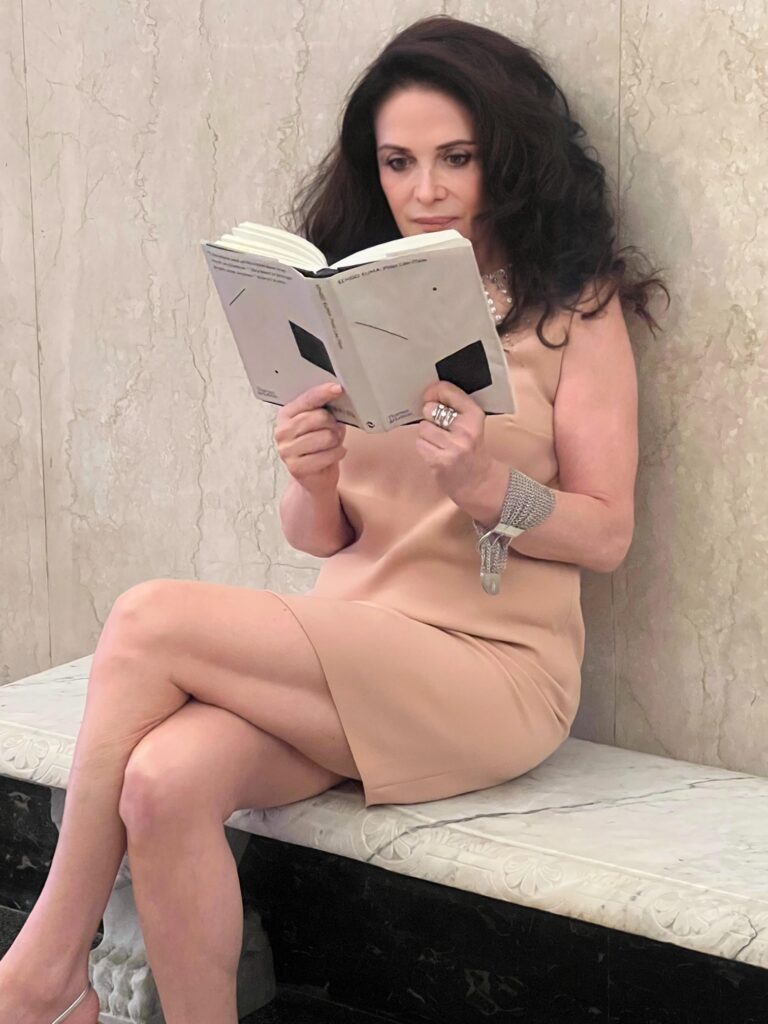

I am a longtime fan of Japanese architect and theorist Kengo Kuma (b. 1954). He has forged a fascinating and intriguing contemporary interpretation of traditional Japanese buildings, which, in my opinion, is the ultimate contemporary reflection of his native Japanese culture and its people. I have hosted him on my podcast, and I refuse to go to Tokyo without his pocketbook Life as an Architect in Tokyo, which serves as a tour of the city’s architectural gems and hidden alleys.

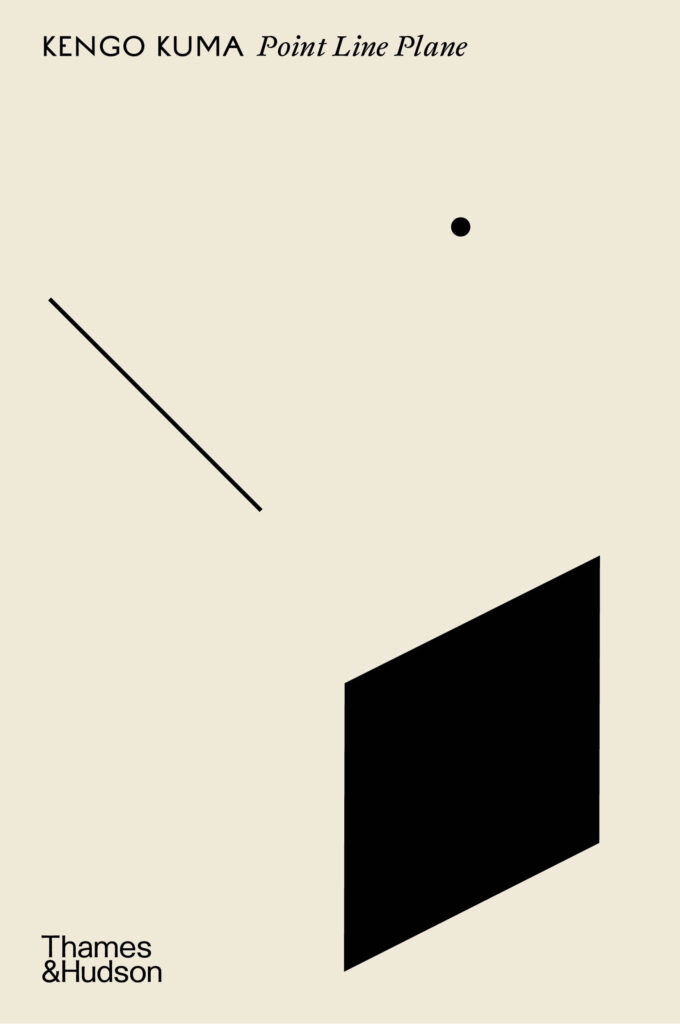

I appreciate the way in which Kuma’s architecture always looks as if it grows out of nature yet also corresponds with technology, sustainability, and human life. His architecture is always modest as well as he, despite having spanned continents. I admire his visions, and always find his writings and philosophy fascinating lessons on the way architecture has come to shape the world. I was thrilled when his latest book, a collection of writings entitled Kengo Kuma: Point, Line, Plane (forthcoming on October 8th, published by Thames & Hudson) was announced and recently published. The book serves as another divine experience of diving into the fascinating world of architecture. Through talking to Kuma and reading his works, I have learned not only to look at architecture differently, but also to recognize the layers of meaning contained in buildings of the past and present. His profound knowledge of architectural history and theory enriches his ideas, turning his discussions into fascinating and educating encounters, while bringing an awareness of how complex the profession of an architect really is. The title of the book was taken from Kandinsky, a strong influence on Kuma whose collection of lectures, Point and Line to Plane, captured his theory of how geometrical, physical, aesthetic, and spiritual concepts coexist.

In his new book, Kuma takes us on a long journey through the roots, meanings, and allure of the story of architecture of lines, planes, and points. He does this by revealing how his constant encounters with the history of architecture over time has come to shape and enrich his own vision. The breadth of his inspirations to create his own architecture of lines, planes, and points is immense; from the small wooden house surrounded by rice fields where he was raised, to the genius of Florentine Renaissance architect Brunelleschi, to Buckminster Fuller’s experimental domes, to Kenzo Tange’s radical and successful approach of dismantling concrete into lines when translating wood construction to the material of his day, to the German Expressionist Bruno Taut and the way in which he emotionally embraced Japanese architecture—suggesting “his sensitivity and vulnerability as a human being and as an architect”—and finally to the indigenous Ainu houses, or cise, which are the traditional dwellings of the Ainu people of Hokkaido, Japan.

According to Kuma, architecture of lines brings air into buildings in a way that solid volume architecture cannot. He makes a distinction and comparison between the two throughout the essays. When Le Corbusier was taken to the Katsura Imperial Villa, he tells us that his reaction was, “too many lines.” Kuma describes how the job of the architect of the lines is much more complex and difficult because he has to connect those into walls. His National Stadium for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics is the ultimate example of labor intensive, craftsmanship-driven, poetic architecture, with the entire building being constructed of small pieces of timber gathered from all over the country. Another spectacular example of his linear architecture is the Hiroshige Museum of Art in Shizuoka, a building I hope to visit next year. With this building he succeeded to translate the iconic rain showers often depicted in the wood block prints of Utagawa Hiroshige—the great master of the ukiyo-e art of the Edo period—into an architecture form, using local cedar when recreating the natural lines of the rain.

Kuma’s personal expression of architecture has always been distinctive and loyal to his principles. Even during his university days in the 70s when Metabolism starred in the world of architecture and contemporary buidligns were constructed of concrete, he never lost his sense of intimate scale. When this style of architecture came to capture the world’s imagination, he found heavy concrete buildings intimidating. Therefore, Kuma never embraced concrete, but rather chose to dig into the roots of the traditional Japanese home. He recognized a point of departure in this modest touchstone of Japanese life, open to an expansion of possibilities and to creating unprecedented contemporary architecture. Kuma was able to build a forward-thinking approach and methodology from his experiences with the traditional way of living in Japan, his quest for meaningful architecture, and from learning the world’s history of architecture. His uniquely developed approach glorifies wooden architecture in the most contemporary way, placing him as one of the world’s most distinguished architects.

Kengo Kuma’s collection of essays is framed by his ability to narrate and tell the complex story of world architecture and his own architecture in clear simple words, which helps the book read like a story. I hope he will soon be selected as the Laureate of the Pritzker Architecture Prize, architecture’s highest honor.

zelo dobro