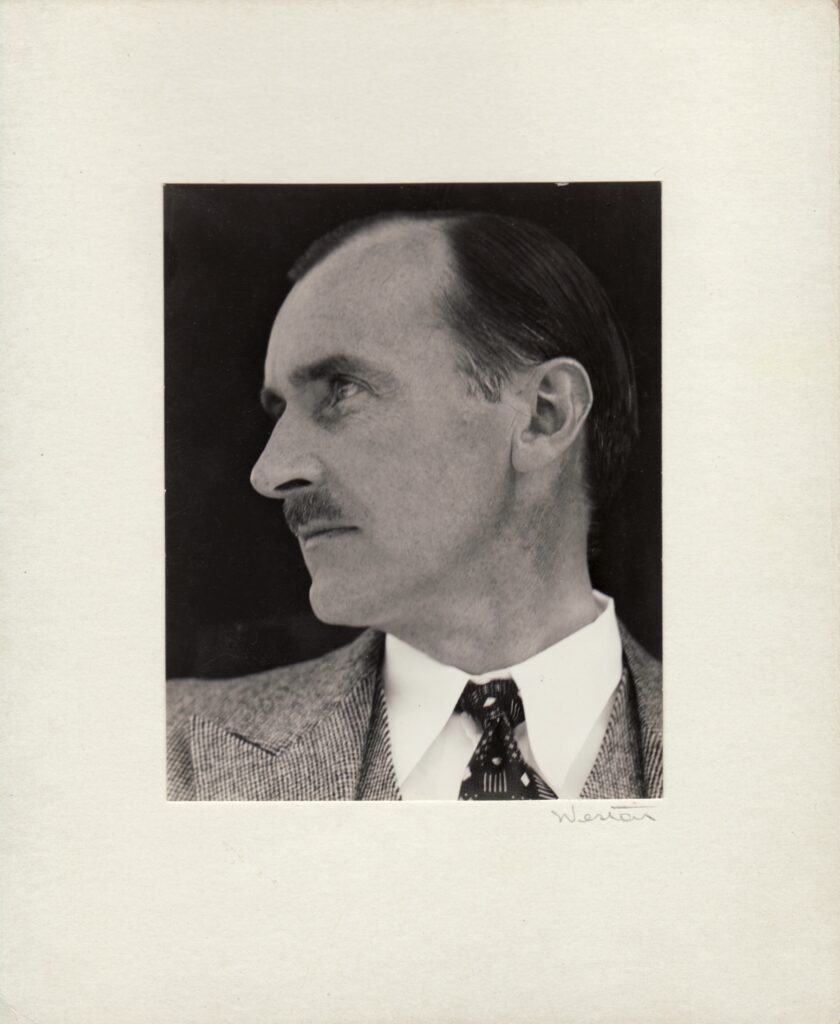

German-born Jock Peters (1889-1934) was an architect/designer who unfortunately did not invest in the effort required to secure his legacy. Perhaps this was because he died early, at the age of 45; perhaps because he was occupied with establishing his practice under financial constraints; and perhaps because the style he came known for did not really become popular until after his death, at the height of the Great Depression. Whatever the reason, Peters’ professional identity, cultural statements, and his entire oeuvre, have largely remained unknown, and his own contribution to modern design has never been acknowledged by those writing its history.

Any architect would tell you that in formulating a legacy, it is crucial to preserve greatness. Look at Frank Lloyd Wright, Charles Renie Mackintosh, and Mies van der Rohe, whose archives are well-secured, preserved, establishing their names in the forefront of the prestigious pantheon of modern design, and gaining cultural primacy. Ask anyone to name famous architects and you can be assured that their answer will include those three. But Jock Peters has never enjoyed such accolades. Now, design historian Christopher Long has published a monograph ‘Jock Peters, Architecture and Design: The Varieties of Modernism,’ that sheds light on the accomplished designer, and places his achievements in the context of design history. Long, Professor of Architecture at the University of Texas at Austin, is an experienced historian who knows the job, and is able to excavate little known gems of material culture; his book is a complete survey and an important document that should be included in any library of design and architecture. It all started incidentally. While working on another monograph at the Design Collection at the University of California Santa Barbara, he encountered references to Jock Peters.

Peters started his career on the right foot, and his early years showed promise of a great future. After apprenticing under a stonemason in Hamburg, and attending a building trade school, he began to work as a draftsman. In 1913, he went to work at the Berlin office of Peter Behrens, where Mies, Gropius, and Le Corbusier, all began their careers. It was at Behrens’ office that the modernism of the metropolis was born, and together with another architect, megastar Erich Mendelsohn, it was Behrens, the most iconic architecture mentor of all time, who has been credited with transforming Berlin into a mecca of modern architecture.

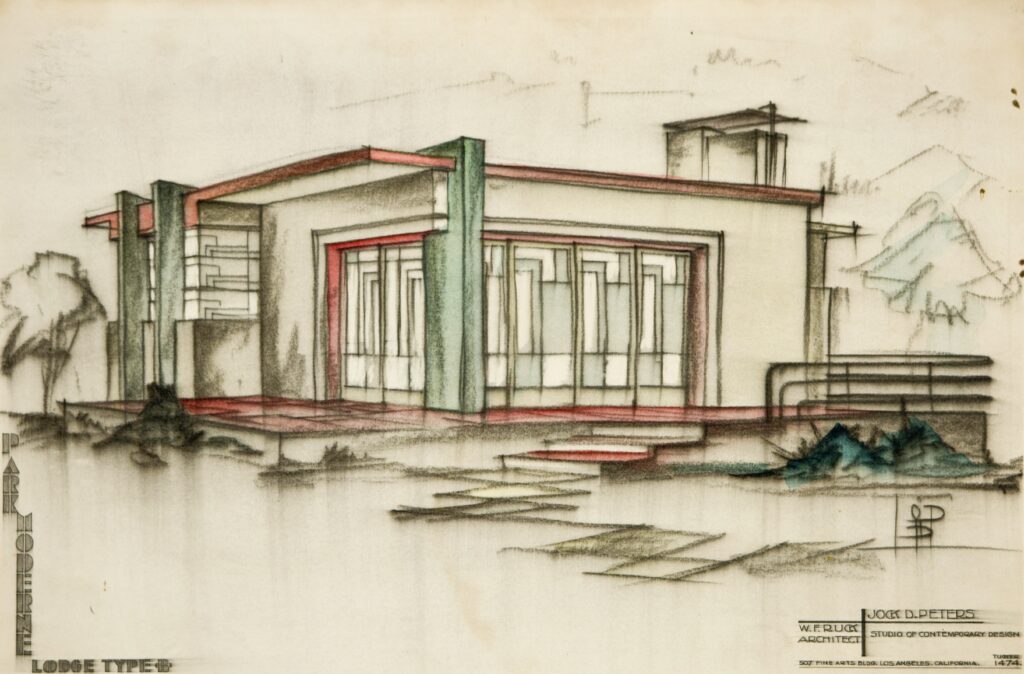

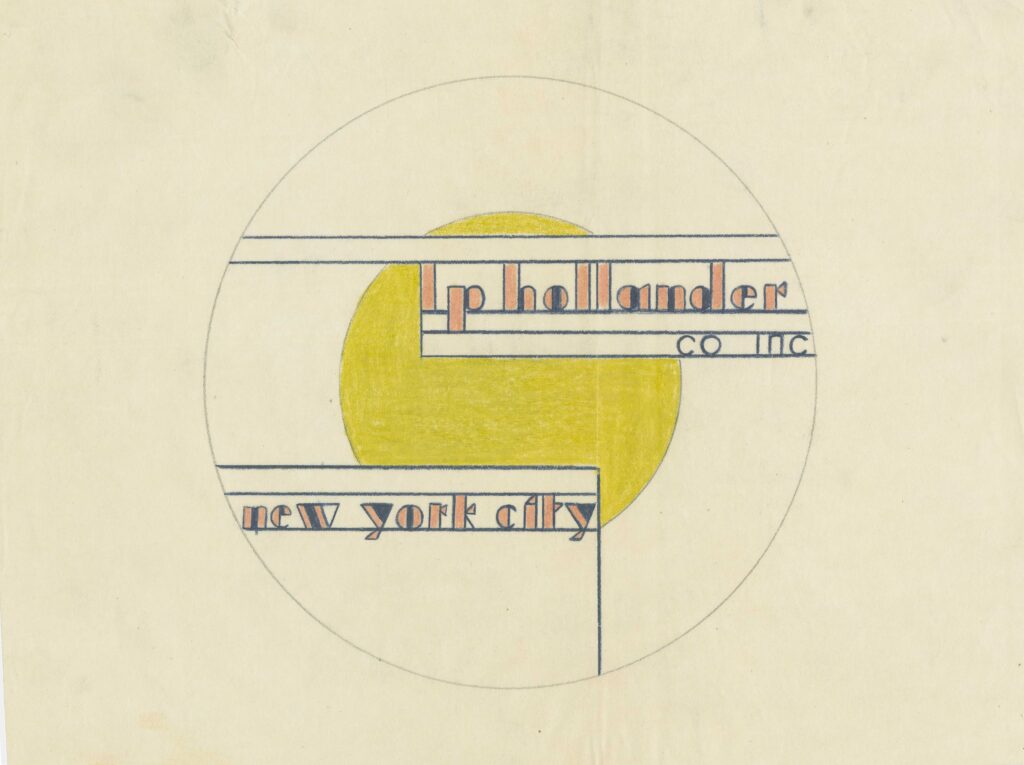

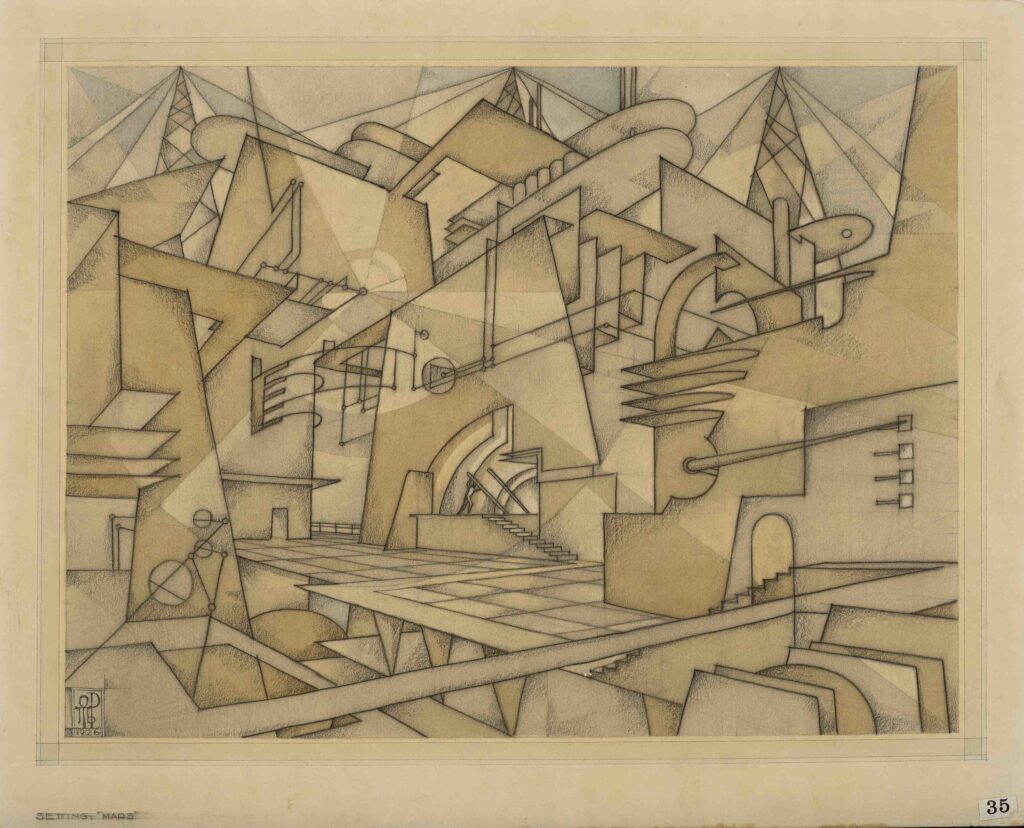

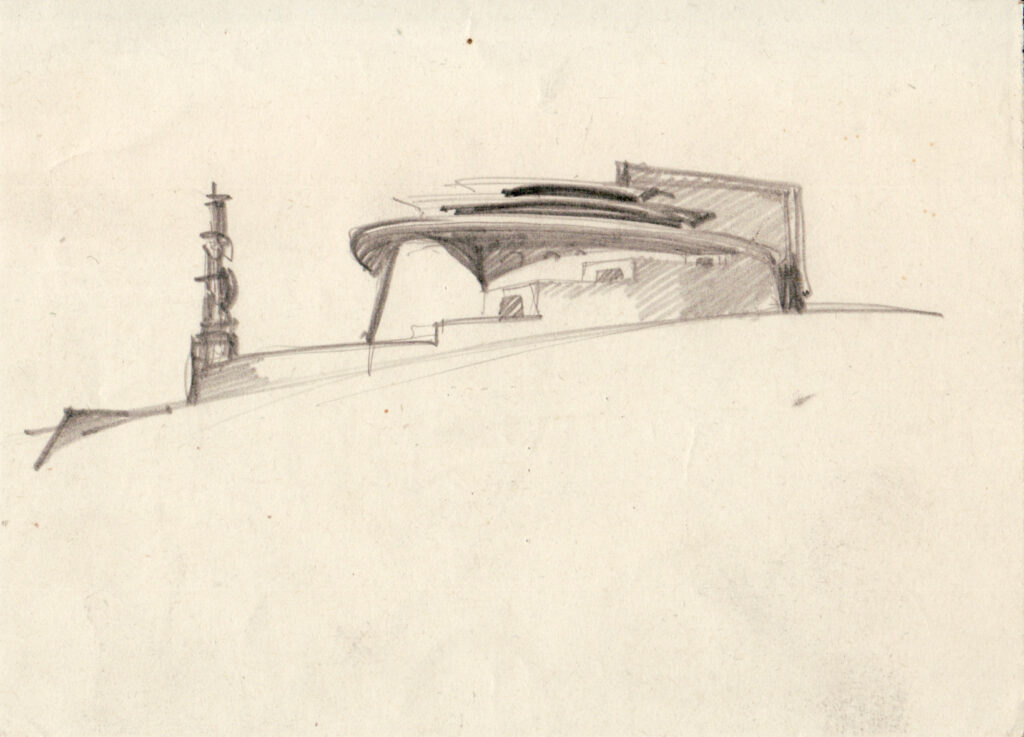

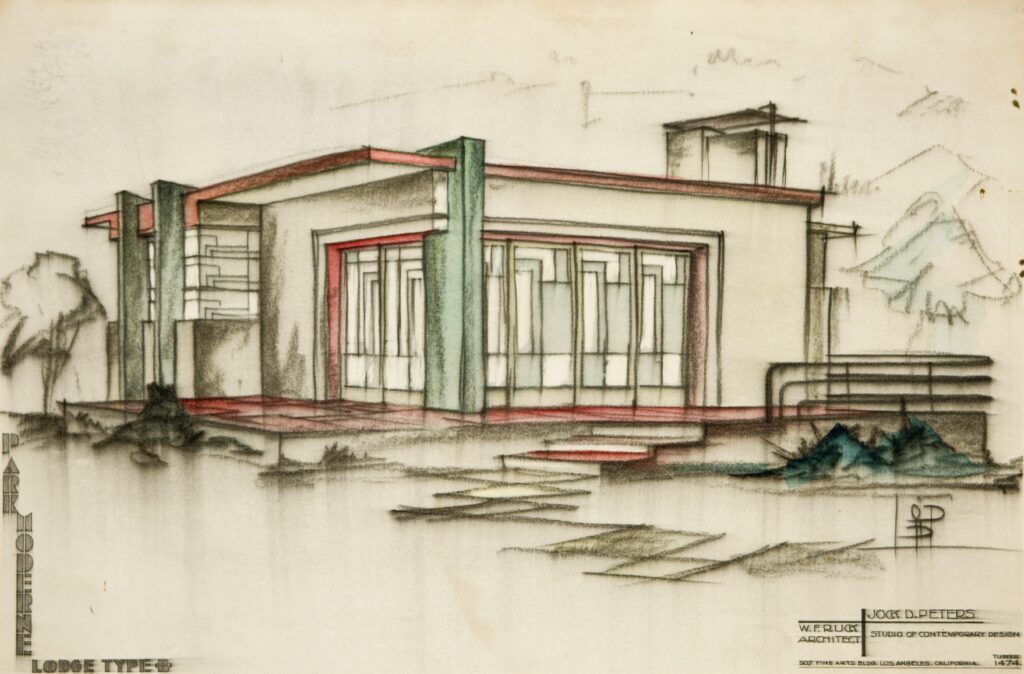

Peters then emigrated to California and was one of a handful of European talents who turned Los Angeles and New York into global laboratories of modern design. Austrian architects Richard Neutra and Rudolph Schindler settled in LA in the 20s, and on the East Coast, Austrian architects Joseph Urban and Paul T. Frankl. They all admired Frank Lloyd Wright, and they were all enthusiastic, visionary, innovative, seeking a new language, perceiving America as the ideal place where the new world would be born. Jock Peters was there, too. During his 12 years in California, he created endless sets for Hollywood studios, interiors for some of the best department stores, and chic residential interiors. He was no less ambitious than Neutra, and no less talented than Urban, but he was lacking when it came to creating his legacy. Long states that Peter had never formulated a signature style. “He never really landed on a particular idiom,” he says, but would rather “try this out, try that out, try a combination of two things, and then he would reduce it or elaborate on it.” But when I look at the endless images of his work in America, I can identify with his Americanized modernism. His most famous project was the Bullock’s Wilshire, one of the greatest retail establishments along Los Angeles’s Miracle Mile.

And something about Christopher Long—he is an amazing scholar who never cut corners, whose ambition in revealing the lesser known is admirable. His contribution to the study of modern design is unparalleled, particularly the chapter of early modernism in the United States. With his monographs of Paul T. Frankl, Kem Weber, and now with ‘Jock Peters, Architecture and Design: The Varieties of Modernism,’ he demonstrates how these influential designers working in the US during the interwar years have transported principles initiated by the Fathers of the Modern Movement to this county long before modernism was eradicated by the Nazis. Much of the book is based on oral history by Peters’s son, Dierk Peters, who shared with Long all he could remember about his father, just weeks before he passed away. And this is the fate of this book.