A solo paper tube marks the home’s entrance; photo Hiroyuki Hirai

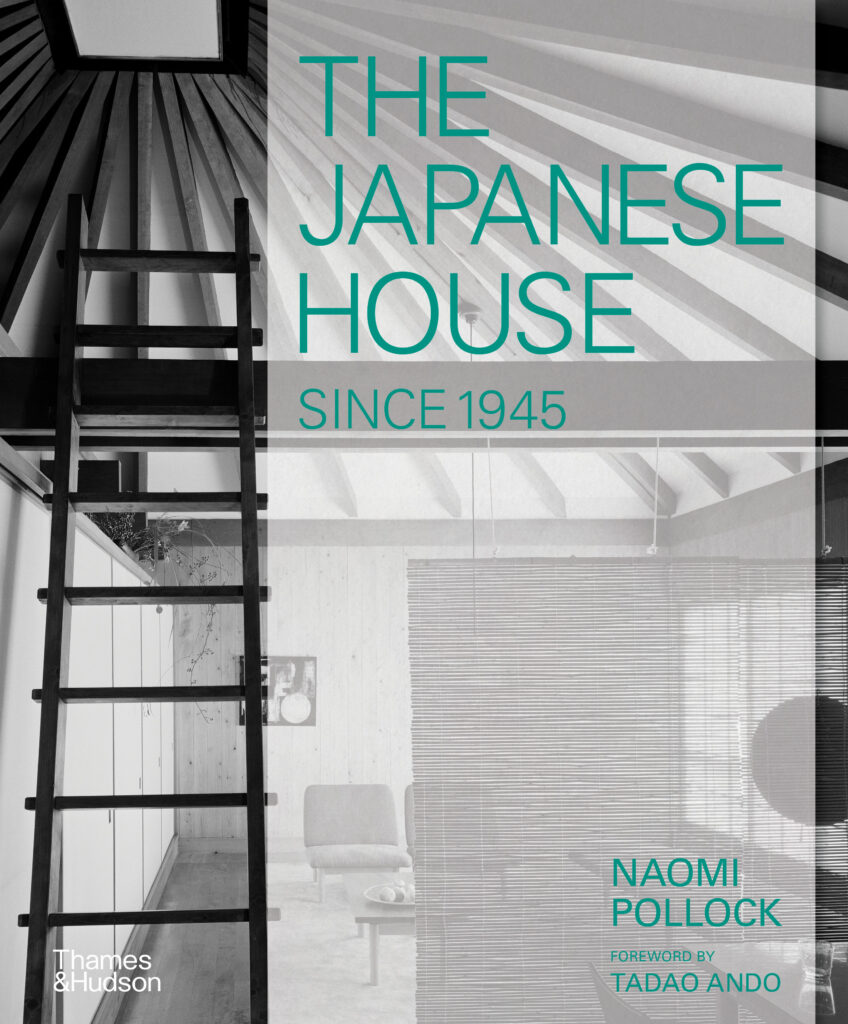

In her recently published book The Japanese House Since 1945, architect-author Naomi Pollock celebrates iconic single-family homes in Japan and the distinct lifestyles that these extraordinary domestic spaces nurture. Examining 97 houses through a material culture lens, Pollock illuminates the way that Japanese residences have evolved over the last 80 years in response to progressing social conventions and values, while always exemplifying thoughtful, innovative design approaches that inspire admirers around the world.

As my Interior Design: Then and Now guest, Pollock shared insights into her journey to discover the intersection of Japanese architecture and culture. Following decades of living and traveling in Japan—fluent in Japanese and drawing on well established relationships in the local architectural community—she set out to uncover the stories behind the facades to understand how the design of domestic spaces impacts the day-to-day lives of the inhabitants, and vice versa. Along the way, she collected original oral histories from the creatives and clients that created the homes, which formed the foundation of her important, new book. Pollock noted that no survey publication on the subject already exists in Japanese. It’s no wonder then that The Japanese House Since 1945 is as lauded inside Japan as it is abroad.

Japanese architecture in the global conversation is recognized for its fascinating forms, inventive use of materials, exceptional craftsmanship, and diversity of expression. For my part, I have long been a fan of Japanese architecture, design, and traditional kogei crafts—and have traveled to Japan regularly to explore and learn more about this passion. What Pollock’s book underscores, however, is that while design and architecture expressions in Japan exhibit enormous variety, they are tied together at their core by the daily habits and customs of those who use them. Japanese starchitect Tadao Ando penned the Foreword to The Japanese House Since 1945 and captured its overarching theme: “The home is a building most intimately connected to the lives of human beings, and as such, it is the origin of architecture and the most effective means of capturing its essence.”

The Japanese House Since 1945 documents and analyzes the shifts in lifestyles and tastes that manifest in single-family homes in Japan against the backdrop of nearly 100 years of historic events—from the efforts to recover from the devastation of World War II and the meteoric modernization of the 1960s through the economic boom of the 1980s and onward to the present—approaching the subject from a number of angles. Pollock’s expertise on the subject is deep. A trained architect with a Master’s from Harvard University Graduate School of Design, she developed her love affair with Japanese culture many years ago, after receiving a scholarship from the Japanese Ministry of Education to study under legendary architect Hiroshi Hara at the University of Tokyo. She has since authored dozens of articles and, including her latest publication, ten books on Japanese architecture and design, all of which are compelling and informative in equal measure.

I could not help but use the 17th-century Imperial Villa of Katsura (near Kyoto) as a point of departure for our talk. To me, this paradigmatic Japanese summer palace, set amid tranquil gardens, is the most beautiful place in the world. Though chronologically outside of Pollock’s scope of study, it has played a key role in defining Western perceptions of Japanese architecture. The site notably attracted pilgrimages by European pioneers of the modernist movement, such as Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier, Bruno Taua, and Charlotte Perriand, and was memorialized in black-and-white photos by Yasuhiro Ishimoto that MoMA exhibited in the 1950s.

The Imperial Villa of Katsura, Pollock said, does in fact have much to teach about Japanese architectural practice in general, despite the fact that it was built for a prince: the separation of skin and structure; continuity between exterior and interior; integration with nature; fluid and flexible spatial arrangements; and emphasis on natural materials, texture, minimalism, abstraction, and horizontality. All of which is guided by a unifying attitude: architecture as a work of art.

Multigenerational living is common in Japan, which has one the world’s oldest populations. Architects have had to develop inventive solutions for “ni setai,” which denotes two households, or two generations, living under one roof. I love Nendo’s Stairway House in Tokyo, the family home of the design studio’s founder, Oki Sato. The supersized staircase, a striking symbol of familial connection, forms the home’s central spine, extending upward from the street outside to the top level inside—an unforgettable entwinement of architecture and urbanism, function and sculpture, the traditional and the contemporary. “I wanted to have a stairway-like structure and greenery gently connecting the upper and lower floors along a diagonal line,” Sato has explained, “creating a space where both generations could take comfort in each other’s subtle presence.”

At the request of the client, a renowned ceramicist, the Sloping North House in Yamaguchi by Hiroshi Sambuichi is inspired by traditional noborigama “climbing” kilns, which have a slanted shape divided into chambers capable of firing hundreds of vessels at once. Like the kiln it’s modeled on, the Sloping North House features ventilation passages at the top and bottom to facilitate the flow of cooling breezes from the forested valley below. What a stunning adaptation of ancient heritage to modern living!

Another common aspect of Japanese life is the need for hybrid live-work spaces, particularly for those outside of city centers. House & Restaurant in Ube by Junya Ishigami offers a dynamic example. The client, an owner of a French restaurant in Yamaguchi, wanted to build a new restaurant that seemed like it had existed forever, where he could also live with his multigenerational family. The architect conceived of a plan to excavate the site so that the sprawling, rough-hewn structure could be underground, integrated into the landscape, with the public restaurant positioned on the north side, the private residence on the south side, and an open courtyard in between. Pollock noted that unlike most architecture, this project was built from the ground down rather than the ground up.

The exquisite houses of Tokyo, with their astonishing architectural solutions to extremely limited space, could fill an entire book by themselves. It’s clear that the current generation of Japanese architects have accepted tight urban conditions with ingenuity and aplomb. Garden & House, for instance, a slim, five-story townhouse in Tokyo designed by Ryue Nishizawa, nestles snugly between two buildings on a dense city block—and still this live-work hybrid is flooded with light and greenery. The building’s tiers of concrete slabs are enclosed in glass, which is setback from the facade to accommodate balconies of lush, camouflaging gardens on each floor. The result is an airy yet secluded urban sanctuary that seems to have no walls at all.

When Pollock’s friends ask her to recommend an architect to design a new house in Japan, she in turn asks them what kind of house they want—because there are so many incredible options. The residence should fit the residents’ lifestyle. And if, like so many in Japan, they want a home that is also a work of art, they should expect the unexpected.

This article was published today in Forum Magazine by Design Miami/.

habitable space; photo Hiroyuki Hirai.

by Ban; photo Hiroyuki Hirai.

element running through the house up to the skylight; photo © Daici Ano.

Photos © Thames & Hudson and © Nacasa and Partners Inc.