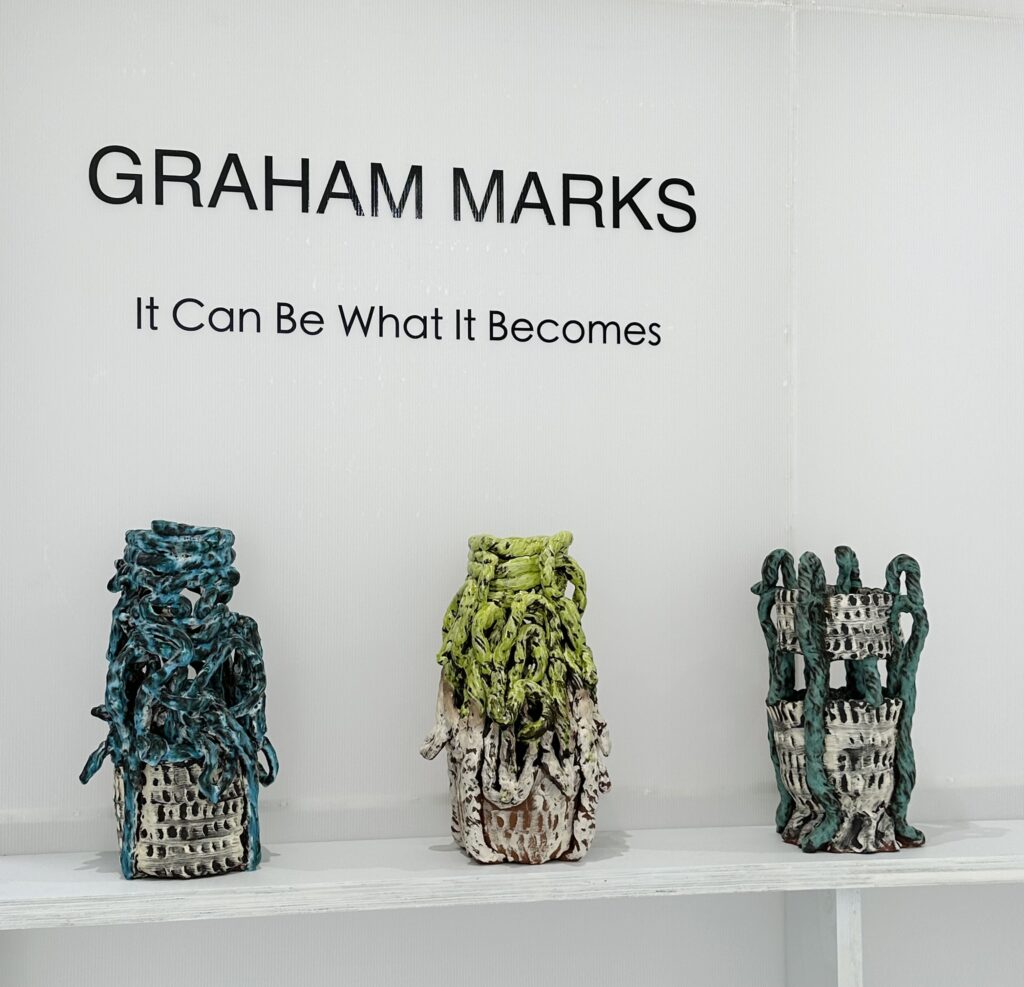

Ceramic artist, Graham Marks (b. 1951), has come back to clay after a three decades of absence. This unique story is the core of his new solo show It Can Be What It Becomes at the Sculpture Space NYC Center for Ceramic Art. Do not expect to see anything like the minimalist, solid, abstract vessels in earthenware or terra-cotta like what he has created in the past, and which demonstrated his interest in ancient cultures and ecological themes. Instead, Marks has returned to the world of ceramics with a completely fresh and unexpected approach. His sculptures are colorful, exuberant, and spontaneous; rooted in his new interest in the history of decorative arts.

Marks started working with clay in 1967, and proceeded to have an accomplished career in the art world. Not only were his pieces regularly acquired by museums across the country—admired by private collectors and signifying the interest in tribal minimalism of that era—but he was also a gifted educator who taught generations of artists the art of coil-built ceramic sculpture. He taught at Kansas State University and Rochester Institute of Technology, before becoming the Head of Ceramics at the Cranbrook Academy of Art. Yet, in 1992, Marks went back to school and changed his career, becoming an acupuncturist who ran a private practice for 25 years, and completely abandoned clay.

Now, in his seventies, Marks is back in the art world and this time, he applies his expertise in the technique of coiling to create a completely different body of work. From Minimalism to Baroque; from the colorless hues of earth to vibrant blues, yellows, reds, and greens; from the planned to the improvisational; from the geometrical to the playful; from vessels to candelabras. Marks has found a new way of expression, which is liberating and filled with excitement. The title of the show, It Can Be What It Becomes, points to the process of working on the new body of sculptures by letting the clay speak for itself.

The turning point happened almost overnight during his visit to the recent show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art called Inspiring Walt Disney: The Animation of French Decorative Arts. This intriguing show came to trace the elements of the European aesthetic movements that Disney animators incorporated into their movies. It was filled with exuberant and decorative styles, teaching us how French Rococo became the core aesthetics in Beauty and the Beast (1991), Gothic Revival in Cinderella (1950), late medieval and Early Netherlandish art in Sleeping Beauty (1959), and 19th-century Germanic Romanticism in Snow White (1937). It is at this show that Marks discovered the possibilities of the decorative to form a new language. His objects are surprisingly sinuous, playful, and brightly colored. The aesthetics, which have become a part of the paradigm of contemporary design, are filled with artisanal approach, humor, layers, textures, and freedom. What I find most intriguing about this show is how he utilizes his extraordinary skills to be reborn into the contemporary.