The attention which Cuban-born designer Clara Porset (1895-1981) has recently received from scholars and museum curators is almost unparalleled, and consequently, her ideas and works are finally garnering the influence they have so long deserved. Wendy Kaplan, the design curator of Los Angles County Museum of Art, first revealed to the American public Porset’s legacy and her strong sense of place in her 2018 exhibition, ‘Found in Translation: Design in California and Mexico, 1915–1985.’ Two years later, the Art Institute of Chicago, in its seminal show ‘In a Cloud, in a Wall, in a Chair: Six Modernists in Mexico at Midcentury,’ revealed the impact Mexico had on Porset’s oeuvre. Her work was once again in the spotlight last year at MoMA’s ‘Crafting Modernity Design in Latin America, 1940–1980,’ which resulted in the museum acquiring Porset’s pieces for its permanent collection. A new publication, ‘Living Design: The Writings of Clara Porset‘ containing her essays, which she extensively published throughout her career, sheds light on her life and thinking. In the concluding session of Furniture Design: Then and Now, I invited curator Ana Elena Mallet, a contributor and the leading authority on Porset, to speak about her other publication, devoted to Porset’s butaque Chair, recently published in the series ‘One on One,’ by MoMA.

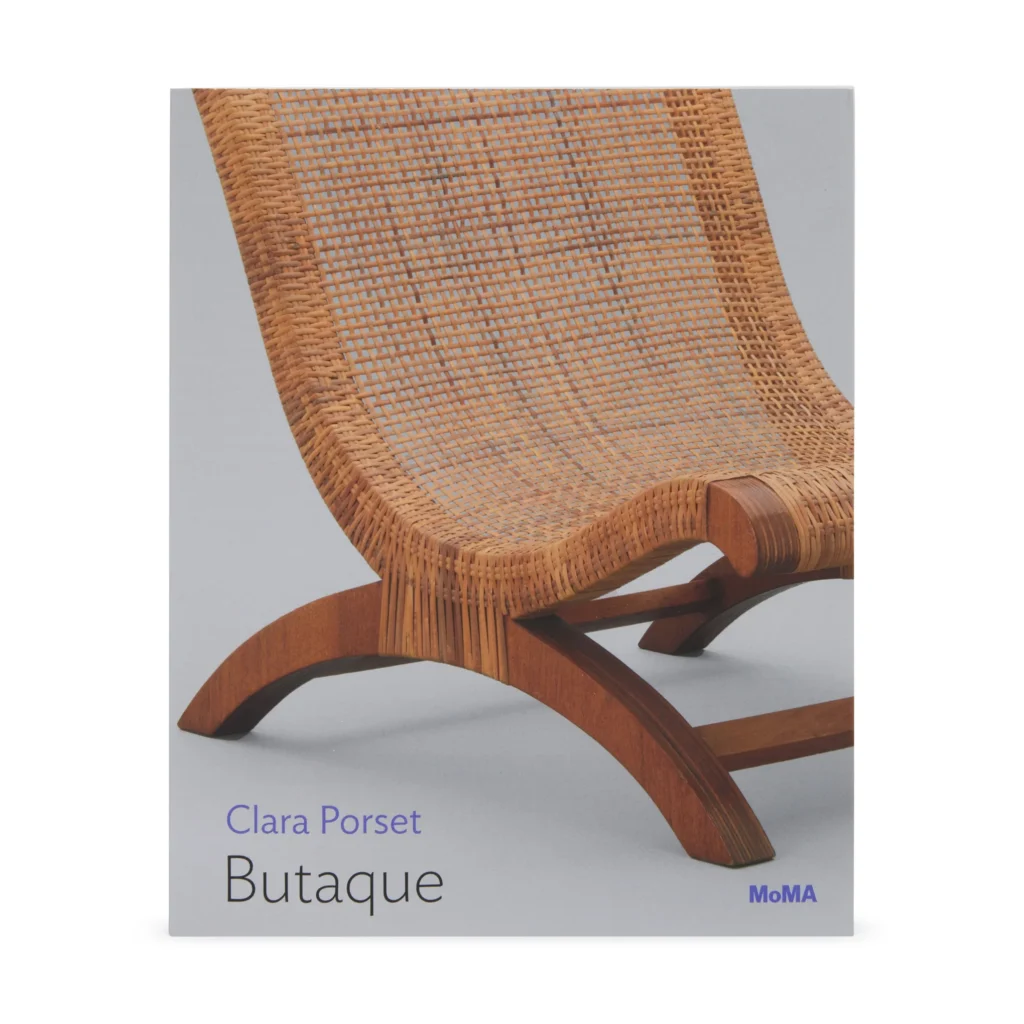

As a scholar specializing in modern and contemporary Mexican design, it is an exciting and busy moment for Mallet, as Mexican design of both past and present is garnering global attention. At the same time, Mexico City, fast becoming the cultural cradle of Latin America, attracted thousands to its annual Art Week in February. Mallet is committed to studying Mexican design culture, and has devoted her book to Porset’s butaque, a humble, low, curved wooden lounge chair, and her most emblematic piece. It has been popular in Latin America for centuries and can be found in villages across Mexico. Furthermore, the butaque has emerged as the touchstone Mexican folk material culture, famously acquired by US President Thomas Jefferson for his home, Monticello, in the early 19th century.

For Porset, the butaque was the ultimate reflection of the successful quest for revisiting the Colonial past and for turning the vernacular into the modern. To her, more than any other form or object, it was the ultimate expression of Mexican identity. She created a number of ergonomic adjustments and adaptations that tuned this vernacular piece into something quite modern, comfortable, and hygienic. In an interview for Art and Architecture Magazine in 1951, Porset told American architecture writer Esther McCoy, “My furniture is said to have a Mexican character. If so, it is a natural result of the objectives I seek; for I design chiefly for Mexicans and strive to produce shapes, as adequately as I may, for their specific conditions of living and their active needs, which are also specific.” Today, a young generation of designers in Mexico have adopted much of Porset’s vision and particularly in their quest to connection to the heritage and to bring national identity into their contemporary pieces.

On the butaque, she famously said, “This influence is most noticeable, because the chair is the type of furniture most closely linked by its proportions and its shape to the changing life of Man.” Furniture made for sitting must adjust more precisely than any other to the average anatomy of the inhabitants of a region, to the materials that can be found there, to the region’s economic and technical development, and to its cultural habits. The chair is always a regional piece of furniture and the most representative of an era.” While throughout her life, Porset worked with some of Mexico’s most prolific architects – her furniture is still found in Luis Barragan’s houses – it is with the butaque that she has made history. That chair has come to capture the essence of her vision, of the way in which she constructed her own personal language.

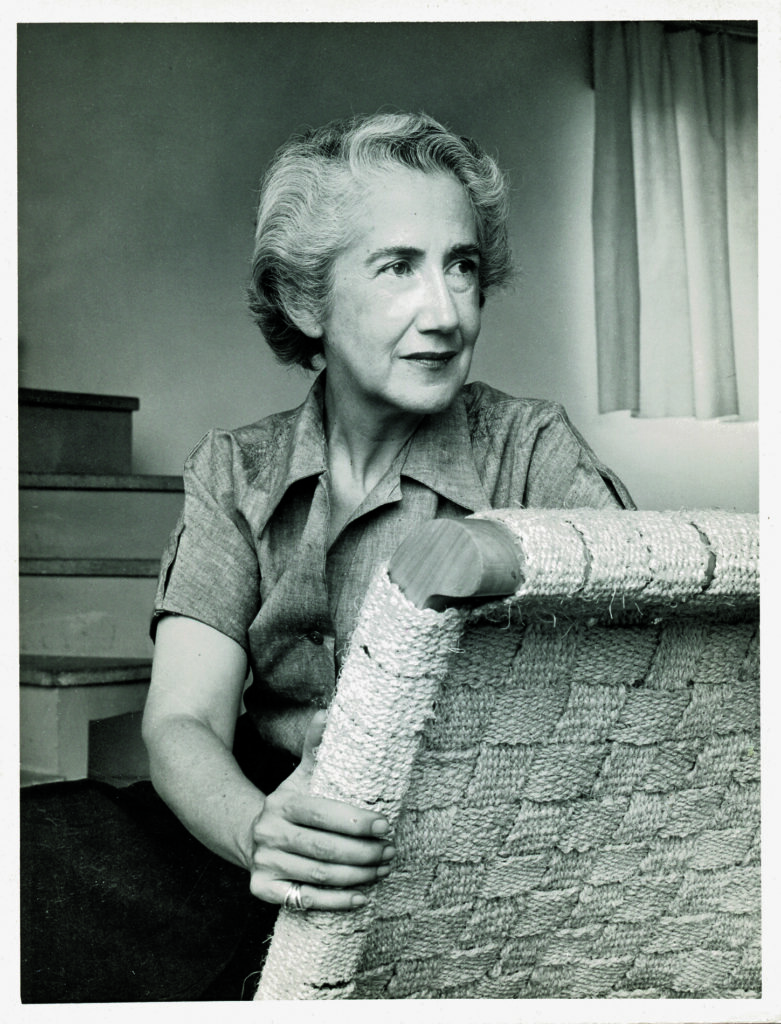

Clara Porset had a magnificent and accomplished life, traveling the world, and obtaining unparalleled world expeditions and education in some of the world’s best design schools, unusual for women of her generation.

She was born into a wealthy Cuban family, attended high school in New York (1911-1914), and took technical courses in architecture and design in Cuba, before returning to New York in 1925, where she studied art, architecture, and design at Columbia University’s School of Fine Arts and the New York School of Interior Design. She went to Dessau in the 1920s, and met both directors of the Bauhaus: Walter Gropius, whom she later called “…a leader in the field of pure and powerful creation,” and Hans Emil Meyer, with whom she forged a friendship when both ended up living in Mexico City. In the late 20s, she continued her studies in architecture and furniture design at Henri Rapin’s studio in Paris while taking classes at both the École des Beaux-Arts and the Louvre.

Upon returning to Cuba in 1932, she served briefly as artistic director of the Technical School for Women, but due to her political views, she was forced into exile in Mexico, where she married prolific artist Xavier Guerrero and remained for most of her life. It is here that Porset promoted her vision regarding the vernacular and its key place in constructing modern furniture. According to Mallet, Porset belonged to a generation of Latin American designers who sought to revisit the indigenous past. But she also belonged to a generation of female designers who sought to forge careers and to design—previously a domain belonging exclusively to men.

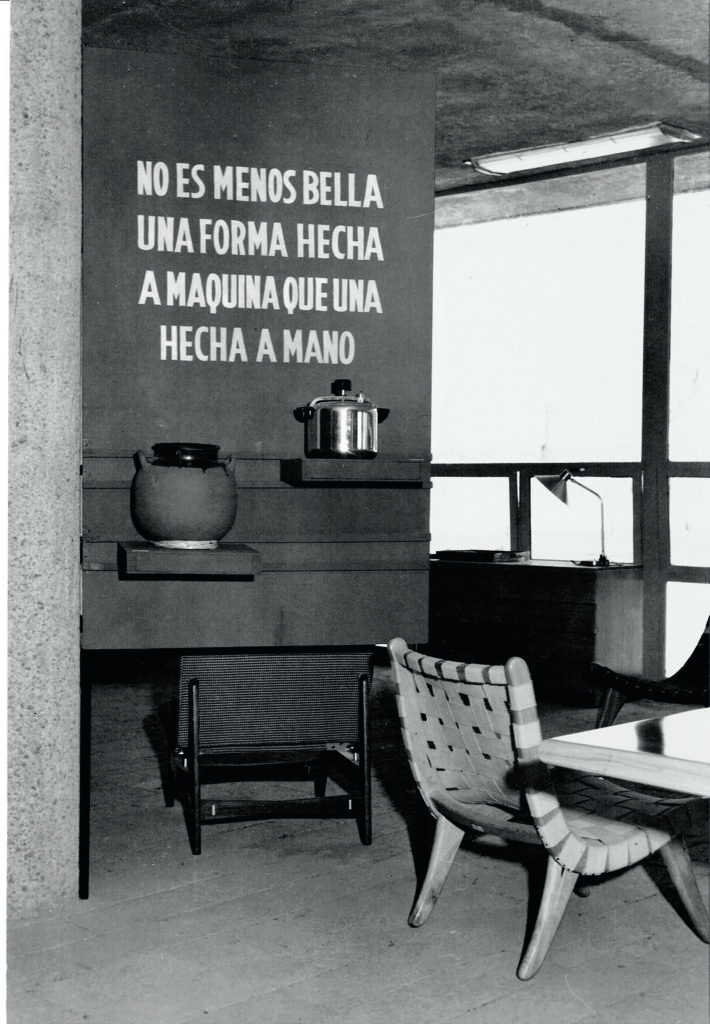

A 1948 International Competition for Low-Cost Furniture Design by MoMA, addressed the demand for affordable housing and inexpensive modern furniture suitable for compact living spaces following the Second World War. Both Porset and Guerrero submitted an entry. The leading role of MoMA in the definition and dissemination of so-called Good Design, with a focus on domestic furnishings, appliances, and industrial design, reflected Porset’s own vision, as she believed that “a machine-made form is no less beautiful than a handmade one.”

Why did Porset remain in the shadow for so many years? I think it is clear. While her furniture was not as heroic as that designed by her contemporary female designers Eileen Gray and Charlotte Perriand, and her public persona was not as glamorous as her contemporary American designers Ray Eames and Florence Knoll, her oeuvre is no less fascinating. But she is now fully revealed, possibly due in part to the special attention paid to female designers of the 20th century, or because of a new interest in Latin American design, or due to her inclusion of the vernacular in modern design. Certainly, Clara Porset is the new star of the design world and she is having a moment of legacy as both furniture and interior designer. When she died in 1981 at the age of 86, she directed that the funds from the sale of her home be used to fund a scholarship for women to study industrial design, known today as the Clara Porset Design Prize, awarded to Mexican design students since 1993. She lives on, as does her iconic mantra – “There is design in everything, in things that are natural and in those created by Man.”