If Italian architect and designer Gianfranco Frattini (1926–2004) were living today with design becoming increasingly identified with Instagram images, he probably would have been more inclined to self-promotion. However, the legendary and prolific architect, who belonged to the generation of heroes who shaped Italian classic modern and turned Milan into the world’s design mecca in the postwar years, was engaged in creating rather than exhibiting and promoting. Publicity had never been his practice. He created some of the most iconic furniture and lighting of the 20th century, working for dozens of companies, including Bernini, Arteluce, Knoll, and Artemide, and was the co-founder of the Association for Industrial Design in the ‘50s, playing a key role in the story of Italian design.

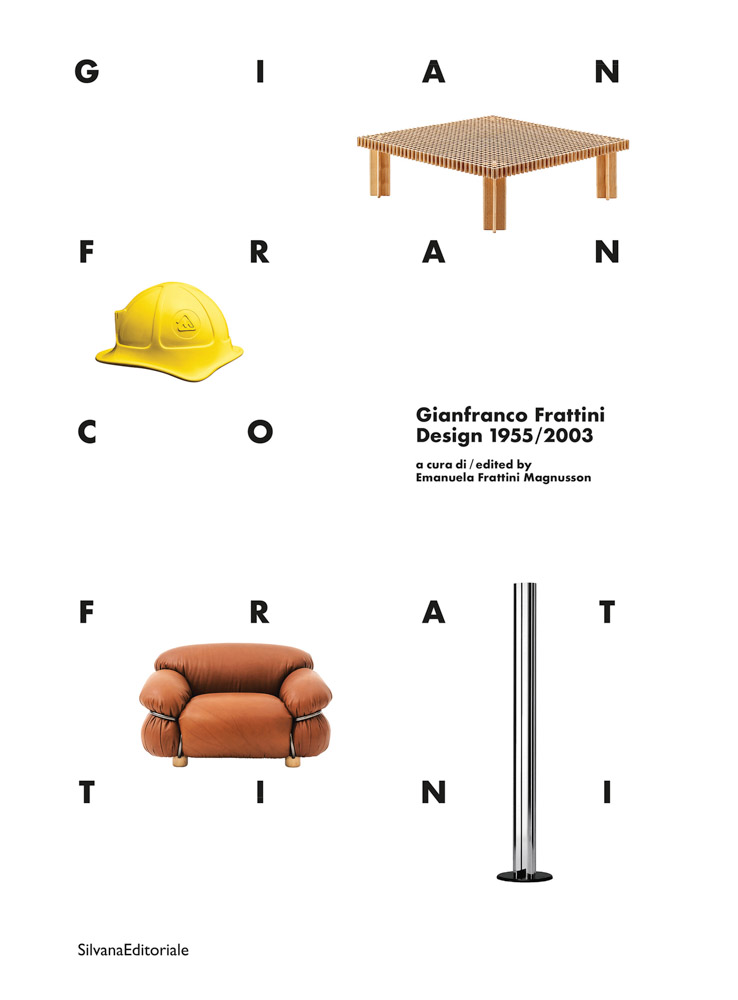

His daughter, New York-based architect, Emanuela Frattini Magnusson, was my guest last week in the series ‘Furniture Design: Then and Now,’ which illustrated her father’s professional legacy and revealed Frattini as the father and designer. We celebrated her recent book, Gianfranco Frattini, Design 1955/2003, published in conjunction with a monographic exhibition at the Palazzo Borromeo in Cesano Maderno in Brianza, which opened during Milan Design Week last year, entitled “Gianfranco Frattini: ieri, oggi, domani” (yesterday, today, tomorrow).

Frattini was born in Padua in 1926 to a Milanese lawyer. As a young boy, his family moved to Milan, where he grew up and whose name ultimately became synonymous with its design renaissance. He was a visionary modernist who remained a functionalist throughout his five-decade career. Like many modernists of his generation, Frattini believed that design had a role in the progress of culture and in its power to change lives. He had never subscribed to the spirit of the Postmodernist Movement, which flourished in his hometown during the 1980s under the guidance of his friend, Ettore Sottsass. Frattini’s mantra, ‘designing from the spoon to the city,’ guided him throughout his career as he created everything from architecture and furniture, to lighting, interiors, and tabletops. Similarly to Josef Hoffmann, who has been traditionally credited for cementing this modernist conception decades before Frattini’s time, he developed an approach in which the architect uses the same sets of tools when creating buildings, interiors, and objects to achieve the harmonious whole, the integrated space.

Frattini inherited this philosophy from his two brilliant mentors, whom he met as a student at the Rationalist Politecnico di Milano—Piero Portaluppi, the key figure in Italian Rationalism, who had fallen into obscurity after the War for his connections to the Fascist regime, and Gio Ponti, from whom, Frattini Magnusson says, her father inherited ‘the fluidity of spaces, flexible floor plan, the use of partitions, and the geometrical furniture design.’ Like both giants, Frattini believed that the architect was responsible for all aspects of the interiors – furniture, flatware, tabletop, textiles, and objects – and like them, he paid attention to detail, constantly seeking quality without compromise while attached to the Italian traditions of crafts. How he transitioned seamlessly from interiors to lighting design to furniture differs, his daughter says, from the typical practice of architecture today, which tends to be specialized.

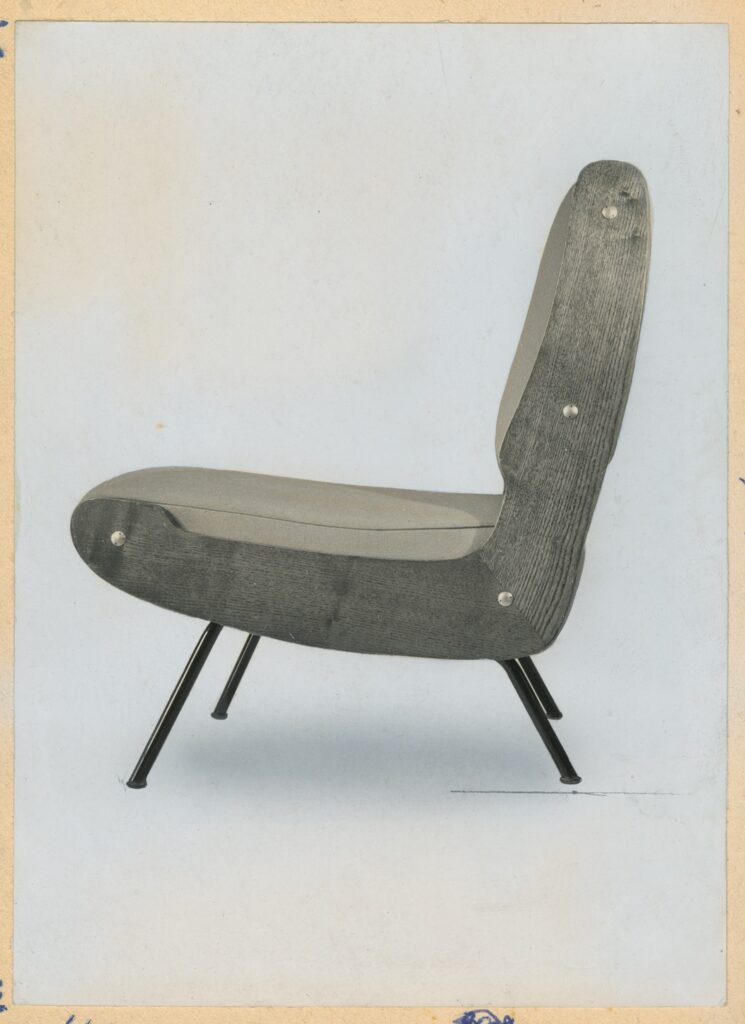

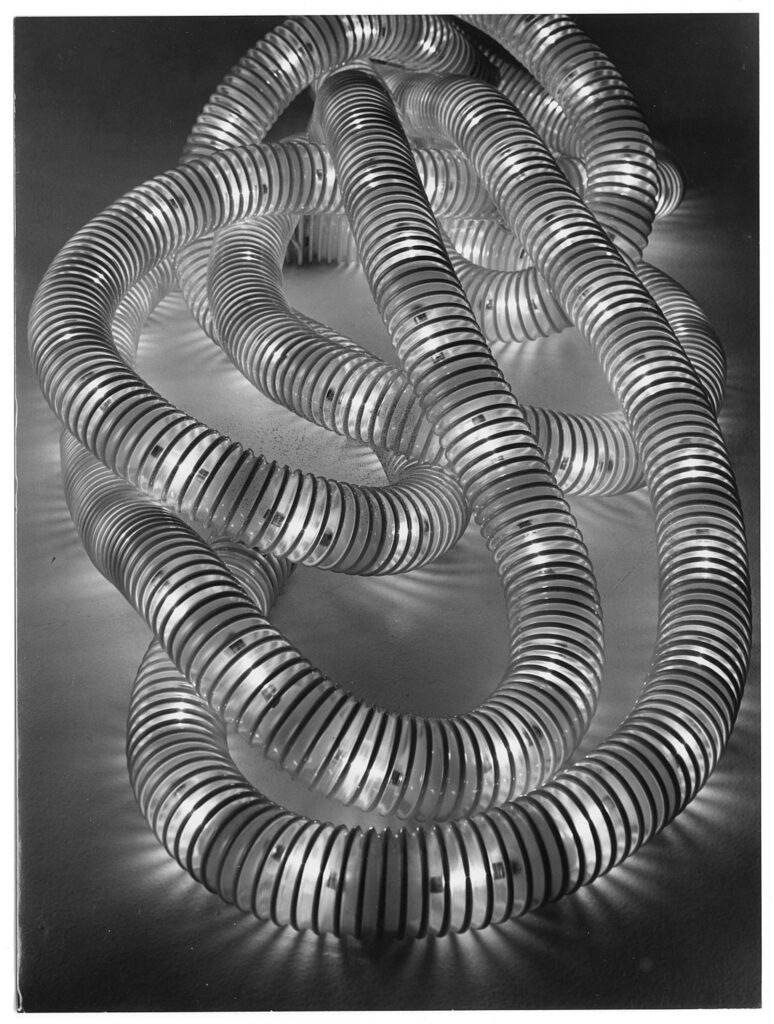

Frattini’s dedication to the process, his ability to work closely with cabinetmakers, upholsterers, artisans, and craftspeople, his love for woodworking, and the workshop space were at the core of his professional identity. He forged partnerships with master craftsmen and, like many other Italian designers of his generation, never lost his ties to Italy’s artisanal heritage in the global postwar design movements, whereas in America and France, the tendency was to focus as much as possible on industry and to look at craftsmanship as a thing of the past. Frattini loved saying that he was born in a workshop. His designs demonstrate how innovation had become the trademark of the classic Italian design of the postwar era. The Boalum lamp, which he created in 1970 in collaboration with Livio Castiglioni, looks like an extended, flexible, luminous tube knotted like a cord. Its shape and concept are completely detached from traditional lighting design.

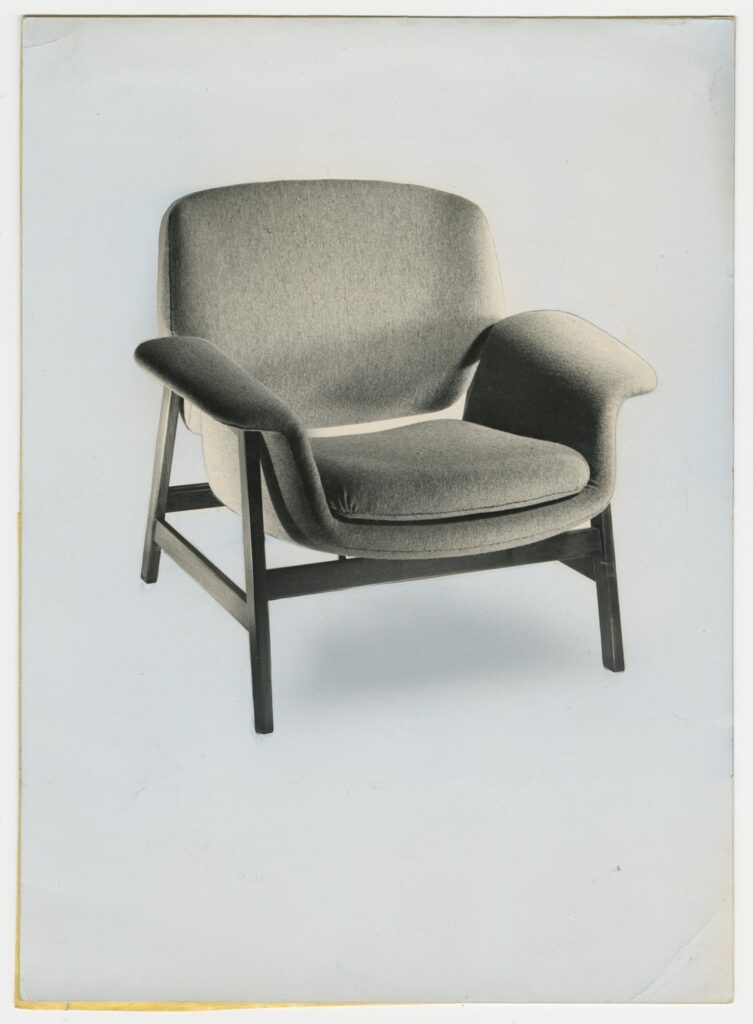

Frattini opened his practice in Milan after completing the first three years of his career at the office of Gio Ponti. The two had forged a lifetime friendship and eventually lived in the same building (which Ponti had designed in South-Western Milan in 1957). Ponti’s office was located in a pavilion in the courtyard of that same building. In Ponti’s office, Frattini met his early clients as well as the man who came to change his life. Cesare Cassina established his namesake furniture company, Amedeo Cassina, with his brother, Umberto, in 1927. In the postwar years, the company was at the forefront of Italian modernity with its transitional approach from artisanal to industrial production. Frattini and Cassina shared the quest to merge industry and crafts but to use the machine selectively and never to try to replicate that which is done by hand. For Cassina, Frattini created some of his most memorable pieces, including the Sesann Sofa and the Bull Lounge Chair, in addition to many custom pieces.

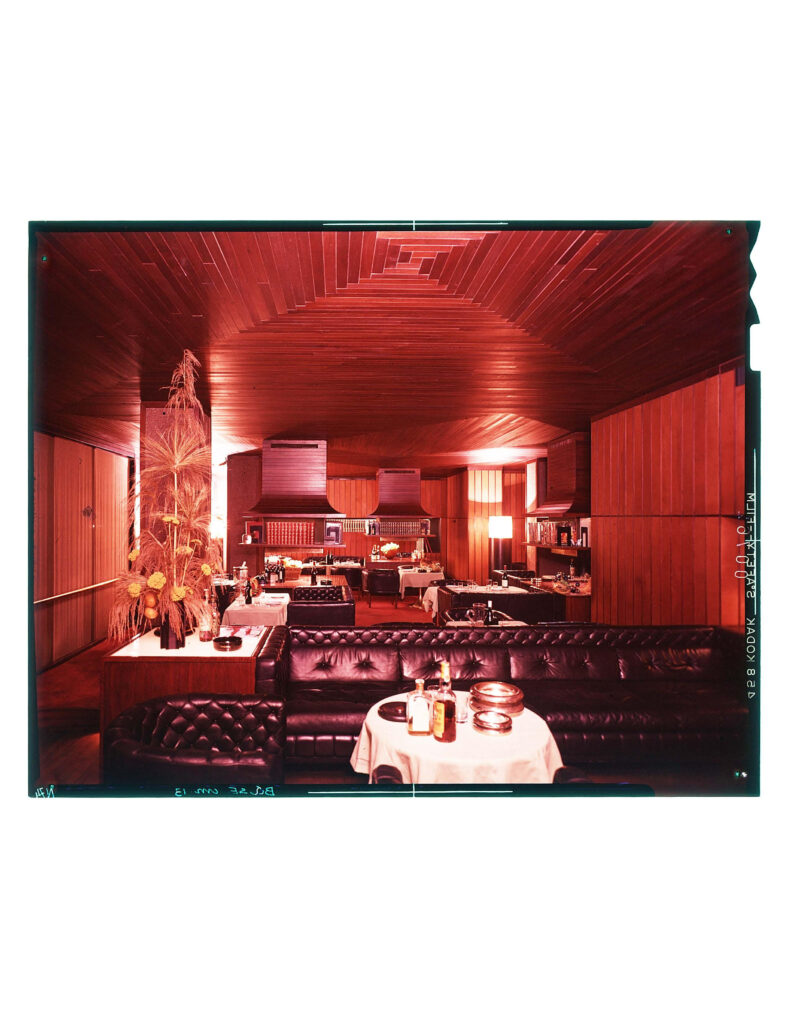

Much of Frattini’s career focused on interiors for the upper-middle class. From the time he founded his office in 1954, he became one of Milan’s most sought-after interior designers. His interiors captured the evolution of his career and the zeitgeist itself, moving from white spaces of the ’50s to textured and layered interiors during the ’60s, a sleek look in the ’70s, and the high-tech look of the ’80s, which culminated in his famed interiors for Hilton Tokyo of 1984, for which he designed the sleek, monochromatic public spaces.

Frattini was a world traveler who found inspiration everywhere. ‘He would open the suitcases,’ Frattini Magnusson recalls, revealing ‘emanated knives by Tapio Wirkkala and Marimekko textiles from a visit to Finland or ceramics and baskets from a tour to South America.’ To develop his ‘Kyoto Coffee Table,’ he went to Japan with his friend and collaborator, master craftsman Pierluigi Ghianda, to study local techniques in joinery. The table surface is assembled of slats cut at 45-degree angles, forming a continuous grid and epitomizing the juxtaposition of the perfection of the grid with the complexity of handcraftsmanship.

Frattini Magnusson and her brother have decided to place Frattini’s enormous archive (consisting of prototypes, models, and approximately 10,000 drawings) at the CSAC (Centro Studi Archivio della Comunicazione) at the University of Parma. The treasure and enormous archive for all visual arts in Italy, situated in Valserena Abbey, was initially founded by critic and historian Carlo Arturo Quintavalle in 1968, making the work of Gianfranco Frattini, which has been gradually digitized, available to the public and scholars. They also digitized the photographic archive at the CSAC, which can be viewed at gianfrancofrattini.com.