f

The newly-opened exhibition of contemporary design from Mexico at the Gallery of Rockefeller Center brings to mind the Center’s historical connection to Mexican art. I am talking about the famed fresco, ‘Man at the Crossroad,’ created by Diego Rivera (1886-1957) in 1934 for the lobby of 30 Rockefeller Plaza, and which was the subject of major dispute that shook the art world of the 1930s. While it initially included aspects of contemporary social and scientific culture, when the press began calling it ‘anti-capitalist propaganda’ while Rivera was in the process of creating the fresco, the communist Mexican artist decided to add images of Vladimir Lenin and the Soviet Russian May Day parade in response. Nelson Rockefeller asked him to remove these symbols, and when the painter refused, the mural was plastered over before it was finished, and lost to time. Like this infamous project, the current exhibition, opened by Mexico-City-based gallery MASA draws on the intellectual exchange between Mexico and New York.

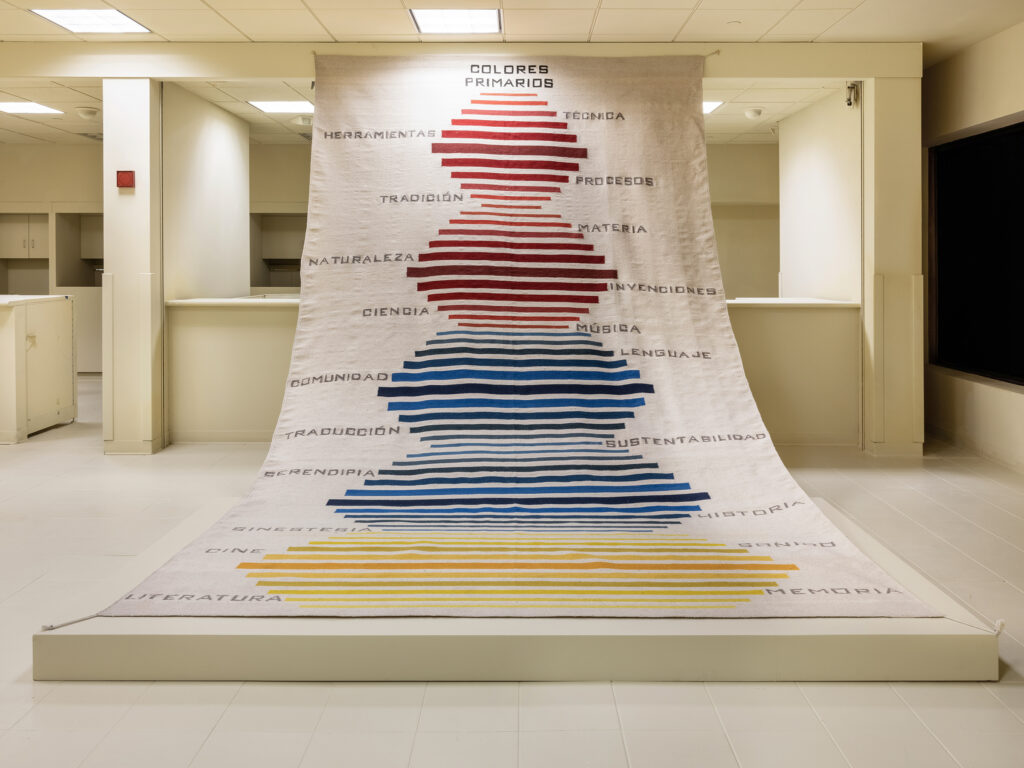

Part of the design month celebration in New York, this show is titled Intervención/Intersección and it presents contemporary Mexican design along with a public installation by Pia Camil to the audience in New York. Exploring the scene of contemporary design in Mexico City last summer managed to pique my interest, so I was thrilled to hear that they are coming to my hometown. This show, perhaps more than others in New York right now, captures the renaissance we are currently experiencing. Not only is it great to see the art world blooming again, but the pop-up exhibition presented in a landmark New York space is, perhaps, a sign that the post-Covid era has at last arrived.

The functional objects reflect the artisanal traditions of Mexico and are displayed in the large space that until recently functioned as the main post office. One object that particularly attracted my attention was a metal bench made of overflowing chain links by architect Frida Escobedo that reconfigures a material of bondage into an object of support. Another highlight for me was an enormous seat crafted in hammered copper by designer Brian Thoreen, made in the state of Michoacan where the traditional craft has been practiced. Héctor Esrawe’s bench made in metal tubes looks fresh and chic; and EWE Studio’s irregular bronze stools are filled with narratives.

The show is augmented with extra layers by the inclusinon of pieces by influential artists of the past who traveled between Mexico and the United States, and who created works influenced by the key Mexican art movements. This includes works by Mexican artist Adolfo Riestra, Isamu Noguchi, and Martin Ramirez. The juxtaposition of the contemporary and the historical is a great recipe for success, making the show more interesting intellectually, historically, and aesthetically. Ultimately, it successfuly captures the relationship between the two cities. New York City and Mexico City.