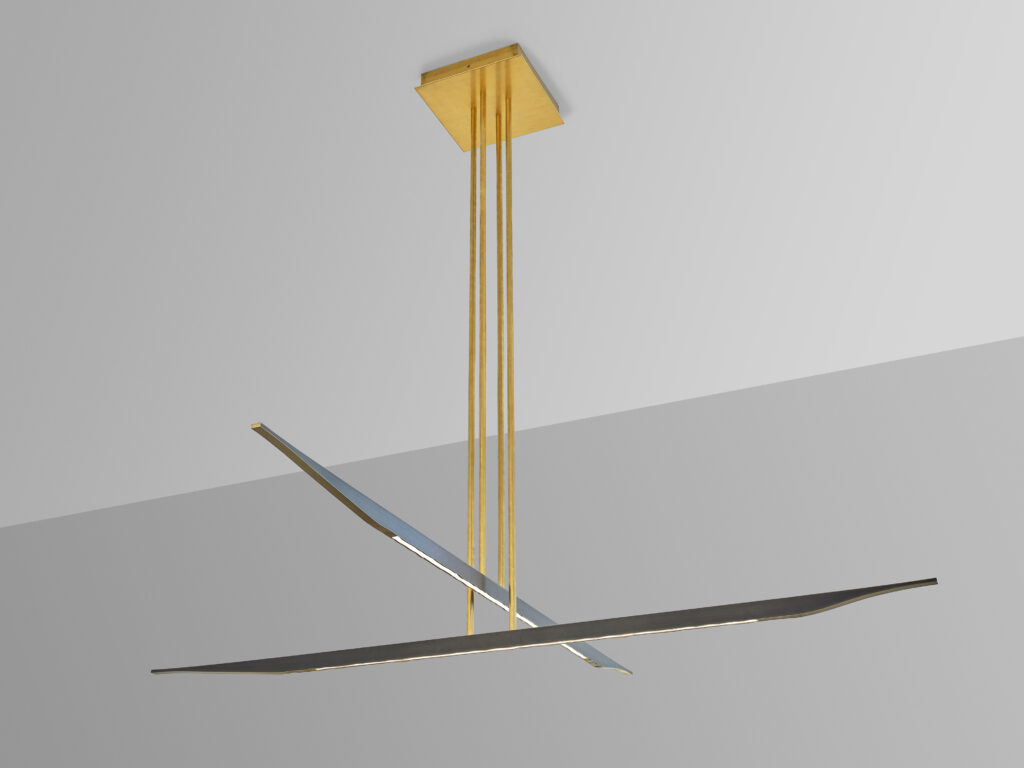

Don’t think about furniture in the traditional context when you look at Douglas Fanning’s furnishings. Think of pieces of architecture, envision open landscapes, shifting lands and supercontinents. This is what the Brooklyn-based designer/maker has in mind when designing his landscape tables and modernist lightings. There is a strong architectural identity to all of his pieces because they are constructed just like buildings; minimalist structures that are crafted to perfection with precision and meticulous technique.

Fanning is a trained architect and received his master’s degree from Columbia University. He decided early on in his career to devote his life to designing and making furniture, but still inspired by his heroes Frank Lloyd Wright, Carlo Scarpa, Louis Kahn, and Eero Saarinen. He lovest the minimalist constructions of New Brutalism that showcase bare materials and structural elements, which was influential to developing his oeuvre. Fanning realized that he derives more joy when creating furniture because it is more immediate than making buildings, and so he started a long journey into the world of furniture design. Over the years his work evolved into what it is today: matured, defined, resolved, and with a recognizable signature language. His pieces—represented by Maison Gerard—appear regularly in design and art fairs, and can be seen in featured chic interiors in some of the finest magazines.

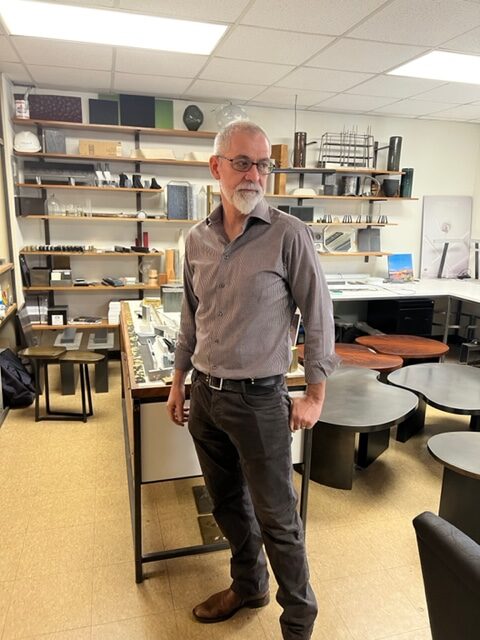

Fanning is a unique practitioner within the landscape of New York’s contemporary design. He is a designer and master craftsman, creating everything in house down to the last detail. He praises honest craftsmanship and is passionate about details and aspects of presentation. With a small and dedicated team of craftspeople and a studio fully equipped with everything from old machinery for metal bending and cutting to the most advanced digital fabricators, he has created furnishings for the contemporary interior: bespoke pieces for those open spaces that require a new type of furniture, with the power to turn interiors into magical entities.

Fanning uses materials such as bronze, brass, and stainless steel, and his techniques are similar to those practiced by mid-century modernists working with sheet metal; cutting, shaping, welding, sanding, and polishing. Despite the pieces being extremely heavy they appear light, airy, fluid, and graceful, as if they are floating naturally in space. This is Fanning’s ultimate power, achieved by pushing the boundaries of the material. The narrative is not only the theme of shifting landscapes, but also the emotional power of the craftsmanship itself and its sensuality. His tables are particularly successful when all of the pieces are interwoven with one another with an organic interplay of the surfaces, making them triumph, more than when comprised of separate parts.

When I visited Fanning at his studio in Red Hook, Brooklyn this week, I was mesmerized by the way in which he singularly focuses on primal utilitarian objects without trying to move to other territories. I find this to be an unusual breath of fresh air in a time when many designers seek to move into the fine art world, and somewhat feel uneased when creating functional objects. He demonstrates thoughtfulness, a critical eye, and a deep knowledge of the market and of history—bringing a fresh perspective to his original work.