As New York celebrates Latin American design and culture with a series of events, conferences, talks, and exhibitions, MoMA is in the lead with its new exhibition Crafting Modernity: Design in Latin America, 1940–1980. Containing a wealth of literature and numerous recent exhibitions in recent years—notably In a Wall, in a Chair: Six Modernists in Mexico at Midcentury at Art Institute Chicago and Moderno: Latin American Design at Americas Society—and a strong presence in the collecting design market and in the contemporary interior, it is hard to believe that it is only in recent years that Latin modern design became known outside of its countries of origin. The exhibition which highlights six counties (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Venezuela) comes to reveal the design culture that developed in those regions in the postwar years, examining the way in which the larger political, social, and cultural transformations came to affect the evolution of modern design. This is meant to illuminate the sudden rise of design in the postwar years when the professionalization of design— not existing before —was born. Art historian Ana Elena Mallet, the Mexico-City based curator, who specialized in modern and conteomporary Mexican design is the guest co-curator of the show.

The years between the end of WWII and the late 70s brought on great economic growth and rapid modernization, which came to stimulate the birth of modern architecture, design, and industry, creating an era of prosperity and hope not unlike other places in the world (i.e. France, Italy, the US, Scandinavia) where modern design became a household commodity. When you travel to Mexico City, Lima, Havana, Rio de Janeiro, Santiago, São Paulo, and other Latin cities, the presence of modernist structures in public, private, institutional, and housing projects from those decades is notable. The architecture of stars such as Oscar Niemeyer and Luis Barragan has been widely examined and discussed. When it comes to the design of objects, both industrial and handcrafted, there is much to be unsurfaced. While the market has been flooded with Brazilian furniture by such stars as José Zanine Caldas, Joaquim Tenreiro, and Lina Bo Bardi, design from other Latin American countries has remained enigmatic. I was therefore thrilled when I first heard about MoMA’s exhibition on Latin American design.

Why place such a broad region as Latin America under one narrative? This was the question that came to mind. After all, the area measures about 2/3 of the entire continent of Europe. We would never think of including design from all European countries in one narrative. In South America, every country has its own political story, its own material culture, and its own traditional crafts. I was looking forward to the curatorial program and to learning a new perspective on how this large and diverse region stands out, and how the shared history of Latin American countries produced homogenous expressions in design. While the exhibition labels repeatedly suggest that in Latin America the idea of modernity was taking a different shape to that of the other parts of the world, due to the influence of the political narrative in the region and that the Latin countries shared similar processes of modernization that inspired the development of domestic design, but this did not come through when looking at the objects on display. It was clear that these regions varied from one country to the next.

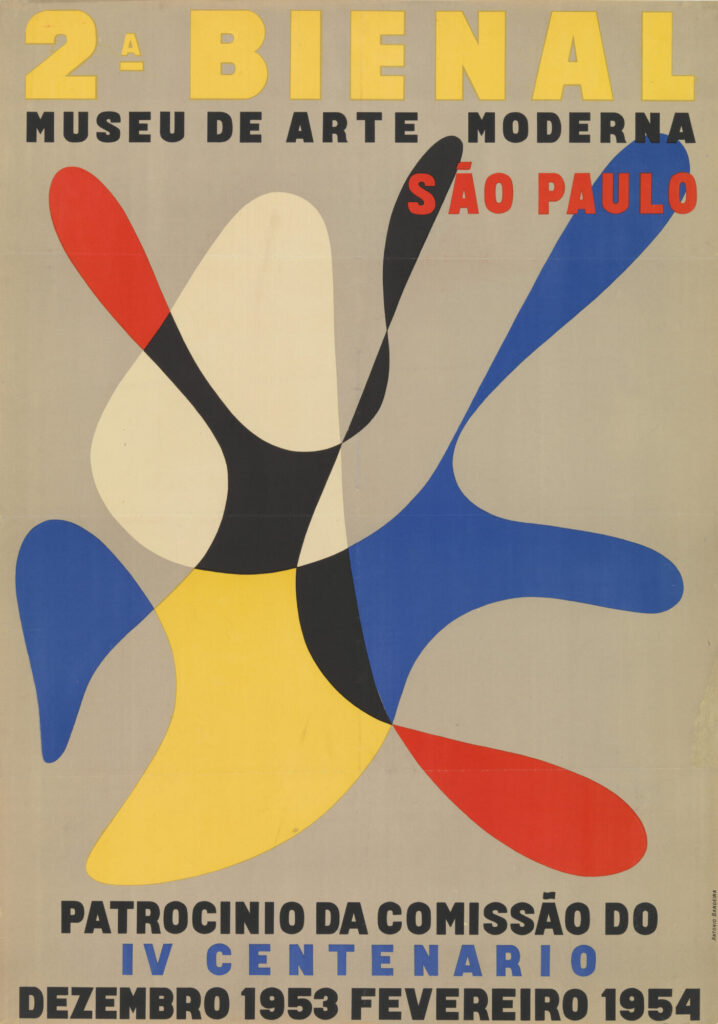

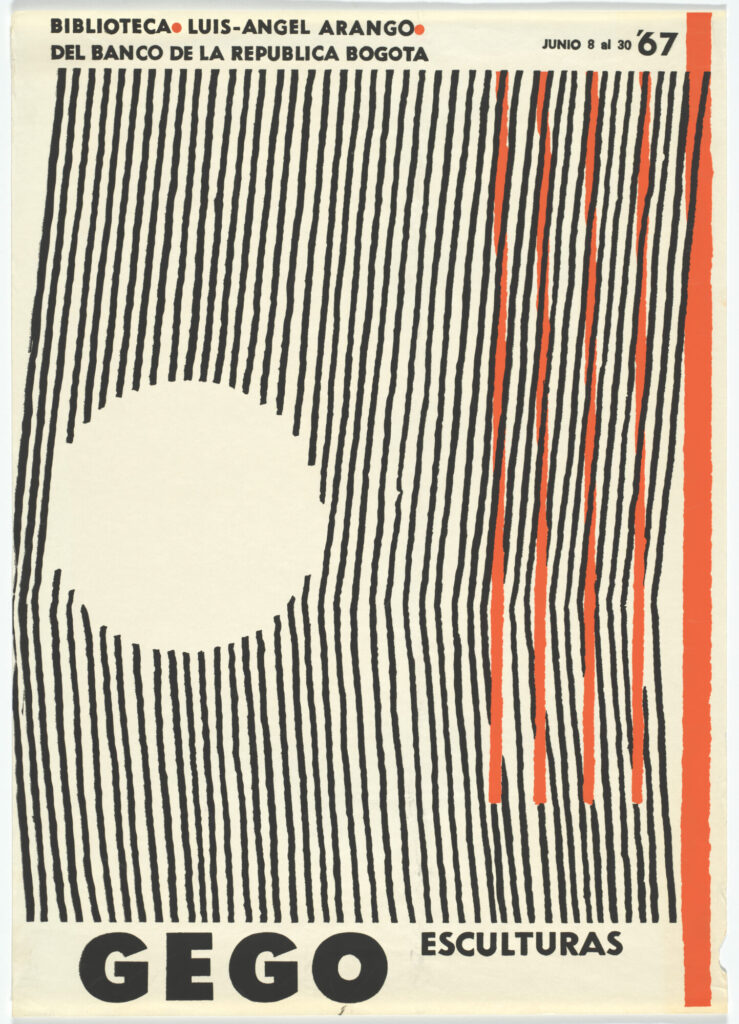

The exhibition includes examples of furniture, graphic design, textiles, ceramics, and industrial design. They are each beautifully installed and divided into groups according to the six different countries and then into various themes (i.e. domestic interiors and modern living, the emergence of the design profession and industrial growth, the creation of visual language, and local craft traditions) which, as a whole, I found inspiring. I was disappointed, however, to see only a tiny representation of counties such as Colombia, Argentina, and Chile. I had great expectations to learn something new beyong the vase body of knowledge produced in recent years, and was hoping for new scholarship of the embodied national sphere as well as unknown design. It is the role of the museum to unsurface historical material, not to simply present known and exposed material.

The story of Brazilian and Mexican design is well known, and yet, I loved seeing all of the pieces I know, like the famed B.K.F. chair, designed in 1937 by three visionary architects—Antonio Bonet from Barcelona, Juan Kurchan, and Jorge Ferrari Hardoy from Buenos Aires— who joined in the Paris studio of Le Corbusier before locating to Buenos Aires and establishing Grupo Austral, which has become an icon. The exhibition presents the example from the collection of MoMA, telling the story of curator Edgar Kaufmann Jr. who visited Argentina and acquired two B.K.F. chairs: one for the Museum, and a second for Fallingwater—his parents’ home in Pennsylvania—cementing this chair as a symbol of modernist design. More than anything, Crafting Modernity: Design in Latin America, 1940–1980 reminds us of MoMA’s incredible history of design exhibitions which has made an impact on the evolution of design and influence on taste in this country. Since the departure of Juliet Kinchin, the curator for the Department of Architecture and Design, the Museum has not put on any exhibitions on historical modern design; this makes this show a must-visit.