James Zemaitis, Director of Museum Relations at New York’s R & Company.

You won’t find any of his interior projects or vast design collections on Instagram, but collector-designer-dealer Michael Boyd has created some of the most magical interiors in Southern California. His taste for superb modern design (and architecture) is so defined, developed, confident, and sophisticated that his talk this week in my program Collecting Design: The Legends left the audience ecstatic with a great desire to live with iconic pieces from the 20th century.

Boyd is arguably the best design mind in his territory: connoisseurship of modernist design. His life’s journey of discovering the allure of modernism began when he was just 18 years old. Although he is often identified with California—where he grew up (in Berkley) and where he has lived for the majority of his life—our conversation started in New York. Because it was in the Big Apple that Boyd’s passion for architecture preservation was born, and it was here that he discovered the power of living with an outstanding design collection in a modernist space permeated with excellence and legacy.

When Boyd and his wife Gabrielle moved to New York in the late 1990s, they purchased the famed triplex penthouse at Beekman Place, home of recently-deceased architect Paul Rudolph, situated on top of a historical brownstone overlooking the East River. The home, completed in 1982, had been the Space Age-inspired testing ground for Rudolph’s architectural vision and his ongoing experimentation with materials and lighting effects. The Boyds lived there long before the building became a New York City Landmark. “Restoring this house,” he says, “was a laboratory for how to restore buildings of historical value”—a pursuit with which Boyd has been largely occupied ever since.

“Everything,” he added, “begins and ends with architecture—from building to design, landscape, furniture, and back again.” Whether crafted, or industrially produced, made in plywood, tubular steel, or aluminum, whether carrying provenance or not, Boyd’s quest for essence and quality, for the power of the avant-garde, has informed his taste and collecting from the very beginning.

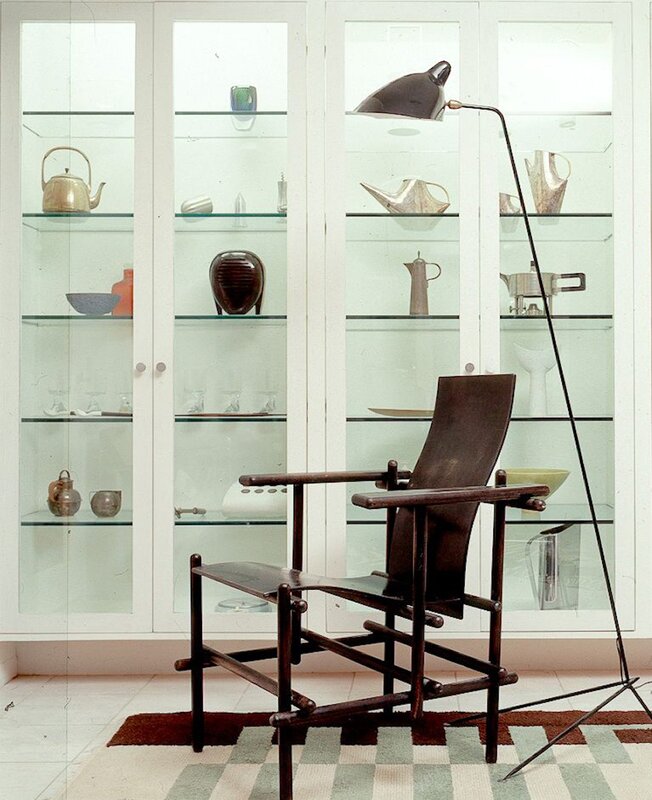

Together we looked at examples of furniture by architects from his extensive collection, made by the pioneers of the modern movement, who experimented with designing furniture as a part of their rationalist oeuvre. Boyd’s taste is consistent, with a clear preference for pieces with strong, architectural forms expressed in materials that embody the zeitgeist. Representing 70 years, from the early manifestations of modernism in turn-of-the-century Vienna to the sophisticated sleekness of the 1970s, Boyd’s collection includes no objects that project a decorative quality or feature extraneous ornamentations. Think of the brilliant purism of masters such as Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Frank Lloyd Wright, Gerrit Rietveld, Jean Prouvé, Charles Eames, Carlo Mollino, and others who championed honest, straightforward furniture design.

On Oscar Niemeyer’s Lounge Chair, which the Brazilian modernist designed later in life with his daughter Anna Maria Niemeyer, Boyd comments that its form summarizes his architectural principles. Niemeyer, a master of sensual, exquisite curves, has left his signature on the chair, “an architecture in small scale,” according to Boyd. The curve, Niemeyer often said, mimics the landscape of Brazil, its rivers and mountains, and the “body of the beloved woman,” in his words. These monumental chairs can be found in the living room of Boyd’s Santa Monica villa, designed in 1963 by Niemeyer himself for filmmaker Joseph Strick. Sadly, the architect never saw the house completed because his support for communism got him banned from visiting the US.

When a question from the audience came as to which piece of furniture is at the top of his bucket list, Boyd responded quickly singles out, “an original example of Le Corbusier’s Club Chair,” also known as the LC3. “But every collector,” he said, “should always have a dream piece that is not yet in his collection.” That’s all part of the magnetism and excitement that drives every collector.

All photos curtesy BoydDesign. This article was published this morning in Forum, the magazine of Design Miami/. To resister for the program, visit the Center for Architecture.