If we have witnessed the rise of studio clay furniture in recent years, the new collection by Montana-based artist Casey Zablocki certainly brings a fresh approach. Montana is renowned for its special local clays, and has emerged as a center for American ceramic art since the 1940s. The present community, nestled in the heart of the rugged Continental Divide, includes professional makers, artists, craftsmen, schools, art centers, and galleries, all taking on roles in a local contemporary clay art movement. Now that the Guild Gallery has opened a solo exhibition of Casey Zablocki’s work, it seems that clay furniture is clearly gaining traction. His pieces are personal and ambitious on many levels.

The Guild is a relatively new gallery, established in 2021 by husband-and-wife team Robin Sandefer and Stephen Alesch, founders of the architecture firm Roman and Williams. It has made a name for representing craftspeople from all over the world, who create art with an emphasis on handcraftsmanship and materiality. But one of the gallery’s most distinctive contributions to the art of dealership in design is the way in which its curators direct the artists to push the boundaries of their own crafts—wood, clay, glass, stone—and to create ambitious works that have the power to transform the contemporary interior. Zablocki nearly gave up on ceramics altogether, until he received a phone call from The Guild, which ended up resurrecting his career, taking his work to new horizons.

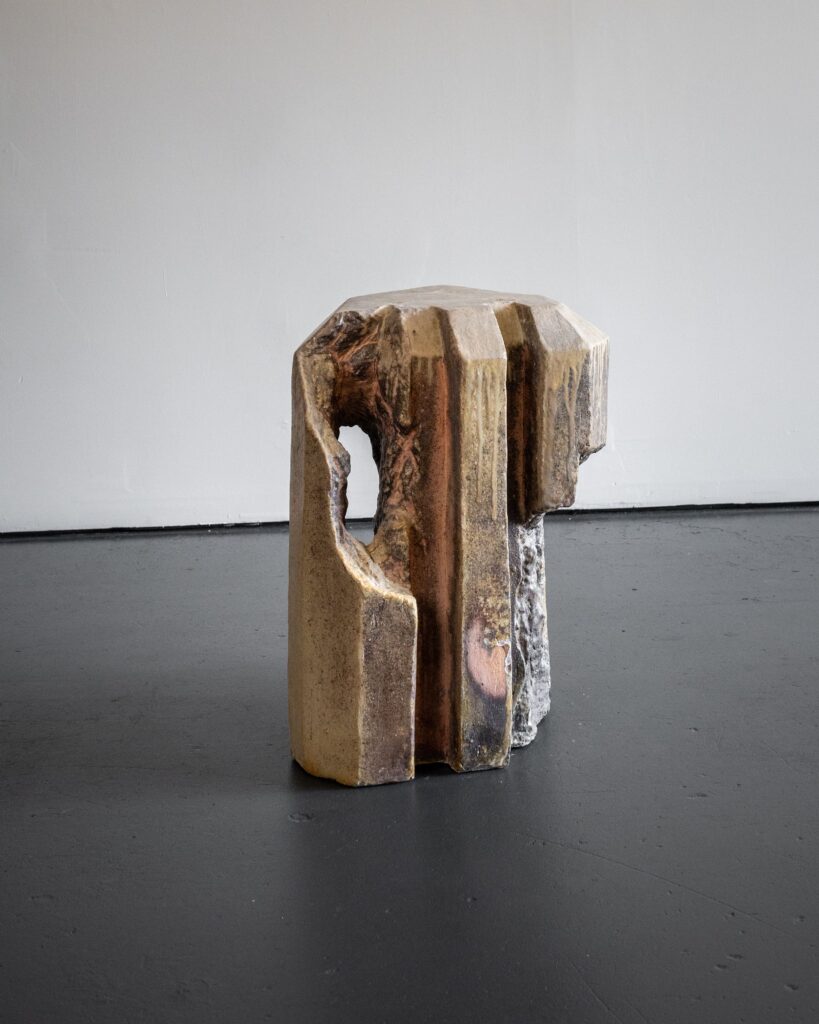

While Zablocki has experimented with clay furniture in the past, it was not until he began working on this exhibition two years ago, and having the gallery’s platform to showcase his ambitious work, that he immersed himself in thorough research in methods and techniques, achieving monumental, innovative, and sculptural ceramic furniture—coffee tables, side tables, chairs—on new levels of scale and intensity. Its poetic quality comes from the narrative and the spirit of the pace; the contemporaneousness is fed by the rhythms, forms, and patterns, and by the techniques employed.

He begins his pieces with skeletons in clay (which he builds), on which he applies hard-core clay, the base. Locally sourced kaolin (porcelain) is then applied, resulting from Zablocki’s exploration of the possibilities of combining various clays with varying elasticity, fragility, and strength. The pieces are completely natural as both textures and colors (celadon green, white, golds, shades of terracotta) are the results of the ash. They are all fired in an anagama kiln – one of the largest in the country – filled with an enormous amount of local wood and fired for ten days.

It is the contrast between the monumental, the raw, and the modular forms and the delicate glazing that stands at the core of these pieces. Unlike many other ceramicists who work in this method, and who seek to control the results, Zablocki is on a constant quest for the surprise. It liberates him. The shapes look as if they exist between the architectural and the primitive, the fundamental and the sophisticated, the natural and the abstract. At times, they resemble ancient rock formations, and at times as if they were excavated from a rock quarry. “All of those tensions between rough and soft,” he says, “weight and weightlessness, refined and unrefined can hopefully be as vast and timeless as the landscape itself.”

The exhibtion will be up until November 14th.