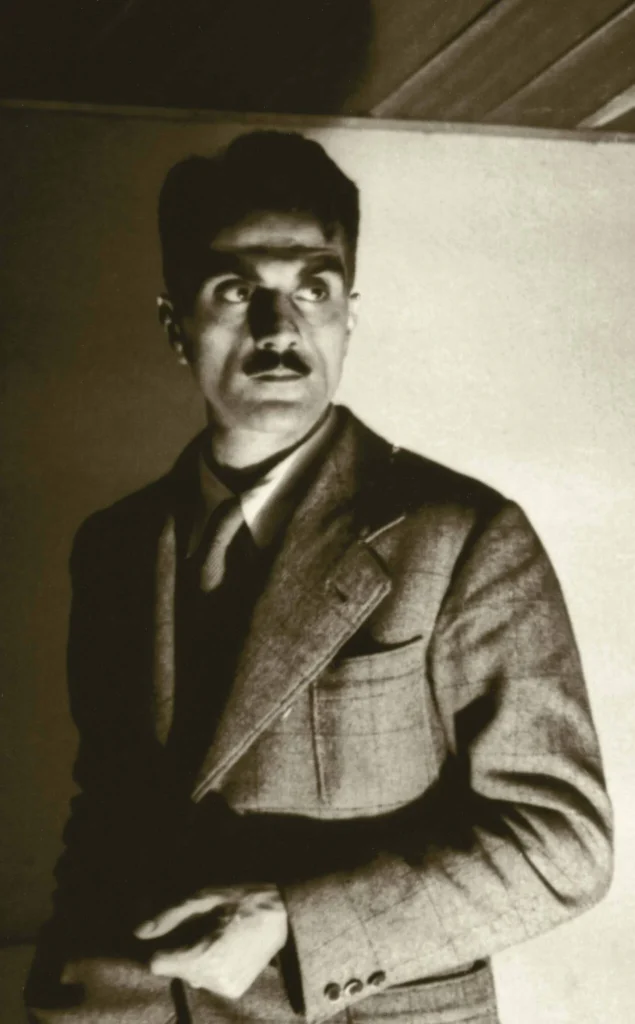

In postwar Turin, he was a stylish, renaissance man, and a performer. In everything he did – designing furniture, interiors, racing cars, photographing women in a series of erotic polaroids, mastering the art of skiing, his selection of fashion and objects that he found – he was an avant-garde performer and a storyteller. While he never married and lived at his parents’ home, Italian architect Carlo Mollino (1905-1973) lived a fascinating and privileged, albeit mysterious life. Expert skier, fast driver, trained pilot, and skilled in acrobatic maneuvers, he was, first and foremost, an architect.

Today, he is arguably a cult figure, the ‘rock star” of the collectible design market, as the rare sculptural, somewhat surreal furniture he created in the ‘40s and ‘50s are greatly esteemed, and fetch millions at auctions. As an architect, however, Mollino’s designs in his hometown of Turin and elsewhere in Italy that have remained enigmas; the Carlo Mollino Archives at the Polytechnic of Turin contain architectural designs for many projects, but only fourteen of them were ever built.

I have invited architecture historian Michelangelo Sabatino, co-author of the new book, Carlo Mollino, Architect and Storyteller (with Napoleone Ferrari, cofounder of the Museo Casa Mollino) as my guest in the series Furniture Design: Then and Now. We explored the way in which Mollino applied his signature vision in furniture to buildings and how storytelling stood at the core of his oeuvre. Each chair, each building, each interior, was poetic, expressive, and constructed from stories.

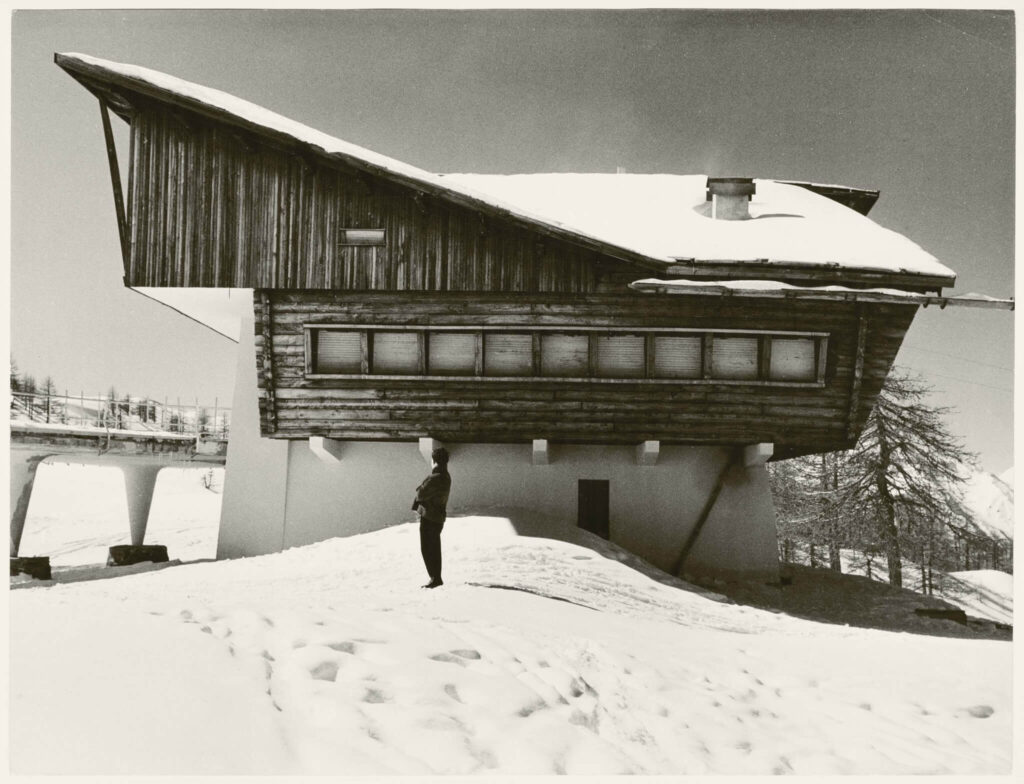

“Was Mollino as a great and innovative architect as he was a furniture designer?” was the first thing I asked Sabatino. “Did he achieve the same level of greatness in architecture as he did in his furniture? Was his typology in architecture as personal and memorable as in furniture?” Sabatino defines Mollino as an “artist-architect” as opposed to an “engineer-architect.” In the ‘50s, he says,. when the brilliant furniture designer was established as an architect, his buildings became great. Exploring furniture design and construction in plywood during the ‘40s enabled Mollino to achieve a personal and expressive style, which he would later apply to buildings. The conversation turned to a wooden cabin ski-station in Cervinia which Mollino designed in 1947 (He also designed an apartment house in the resort town). Sabatino stated that Mollino’s expressive, folded roof of reinforced concrete looks as if it is in motion, a dynamic expressionism which made the building seem as if it were about to take off. Introducing speed into architecture in the same way he had done with his furniture design highlights his connection to Futurism.

Carlo Mollino was born and raised in Turin in the bourgeoise, upper-middle-class family, in a mansion built by his enormously successful civil engineer father, Eugenio Mollino (1873-1953) who had a busy practice, building hundreds of structures throughout his career. Young Mollino never left the home which was filled with art and books; style was not foreign to him growing up. As a child, he expressed an interest in his father’s constructional engineering and architecture work, and studied architecture at the University of Turin.

He never had his own studio and chose instead to work at his father’s studio throughout his career as an archiect. Yet, unlike his prolific father, who subscribed to the eclectic taste and ideas typical of late 19th early 20th century, spread throughout Italy during the interwar years, young Mollino preferred to integrate the Baroque tradition of his hometown into his language, as he was an unconventional modernist. Everything he did was ornate, elaborate, complex, and, like other Italian architects of his generation – Gio Ponti, Gianfranco Frattini, Paolo Buffa, for example – he never strayed far from the Italian vernacular. Instead of machine-age aesthetics, he maintained a close connection with artisanal production, craftspeople, and traditional materials. He was greatly inspired by Italian Futurism, the artistic and social movement that swept the country in the early years of the century, embracing speed, technology, and youth. These were all central to the construction of Mollino’s personal grammar and vision as a university professor and author of a number of important books .

The book, Carlo Mollino, Architect and Storyteller, is divided into three sections. The first, ‘Framing Carlo Mollino’ is a fascinating biographical chapter of Mollino’s life, projects, and visions. The second section, ‘Architectural Stories 1933–73,’ is particularly important. Here, the authors reproduced The Life of Oberon, Mollino’s first novel which he published in 1933 in Casabella Magazine, before he even started practicing architecture. This four-part manifesto, published two years after his graduation from architecture school, is published in English here for the first time. It is a fictional architect working in Turin, named after the king of the fairies in medieval and Renaissance literature, and the character in William Shakespeare’s play, A Midsummer Night’s Dream. This story provides insight into Mollino the person, and also to his brilliant talent of storytelling and constructing fiction. The third section of the book, titled ‘Complete Works and Projects’ contains a comprehensive list of Mollino’s unrealized architecture and interior projects. Each project is accompanied by original sketches, and concluding with a full list of his writings.

Carlo Mollino was a brilliant architect who created furniture that looked like prehistoric skeletons and buildings that looked as if they are ready to fly. His architecture, furniture design, and interiors, were always elegant, mysterious, expressive, and sensual. He embraced ‘modern eclecticism,’ or in the words of Josh Itiola ‘multi hyphenate creative’. Mollino mastered movements and dynamic suspension like no one else, yet, after reading the book, I believe that with his furniture design, Mollino forged a strong personal typology, and its references to surrealism and futurism was unique. In architecture, however, his expression was less powerful.

Photographer Pino Musi was commissioned to photograph Mollino’s surviving buildings, so these contemporary photographs allow us to see the way these buildings look today. This book, published by Park Books is a mandatory addition to any library of design, architecture, and Italian culture.

© Photograph Pino Musi, 2016

Mollino