“The contested intellectual history of Reconstruction [the era] has taught us that structural racism and private racist actions cannot be extricated from society by laws alone… The curatorial charge of Reconstructions [the exhibition], amid a global return to authoritarianism, fascism, xenophobia, and racism, compels us to ask: What cognitive conditions are necessary to think anew about the productive roles race and Blackness can play in conceptualizing future imaginings of cities and societies?”

–Milton S. F. Curry in “Toward a New Architecture Race Theory” for Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America, 2021

Few institutions, if any, have played a larger role than New York’s Museum of Modern Art in defining the architecture and design canon over the last century. Founded in 1929 with a dedication to “the visual arts of our time,” MoMA was the first museum worldwide to launch an Architecture and Design department in 1932 and went on to have a colossal influence over which creatives and movements have been most widely deemed important. But until quite recently, the exhibitions and collections of MoMA’s Architecture and Design department have overwhelmingly favored works rooted in the Eurocentric legacy of modernism. As Columbia GSAPP Professor Mabel O. Wilson noted in her 2019 essay “White by Design,” MoMA’s sizable permanent collection included zero Black architects or designers until 2016 (when only one such object was accessioned). Against this startling background, MoMA’s 2021 exhibition, Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America, represented a landmark, long overdue step for the institution toward correcting the overwhelmingly white canon it helped establish.

“Reconstructions, which features the work of 11 architects, artists, and designers from the African Diaspora, attempts to register an awareness of the absence of Black Americans in the production of architecture and urban design thinking.” Neatly encapsulating MoMA’s first exhibition to explore architectural spaces for and by Black communities, these words were written for the show’s accompanying catalog by my recent Architecture: The Legends guest, esteemed architecture professor and theorist Milton Curry.

Curry was a natural choice to contribute to the Reconstructions catalog. Since graduating from Harvard Graduate School of Design in 1992, he has produced an incisive body of scholarly work—from research, writing, and teaching, to founding and editing visionary journals and his recent position as Dean of the prestigious School of Architecture at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. Illuminating the complex intersection of architecture, urbanism, aesthetics, social hierarchy, and race, Curry has earned an international reputation for progressive thought leadership in the pedagogy and practice of architecture.

During my conversation with Curry, he praised MoMA’s Reconstructions as a crucial moment of reconciliation, a reflection of the advancements that Black people have made toward understanding their place in American culture. The successes of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, he said, formed the foundation and set the bar for today’s energetic social justice activism. And the field of architecture has benefited from growing efforts to recover marginalized histories and experiences and examine more closely (and collaboratively) the housing, public spaces, and living conditions of Black, Brown, and immigrant communities.

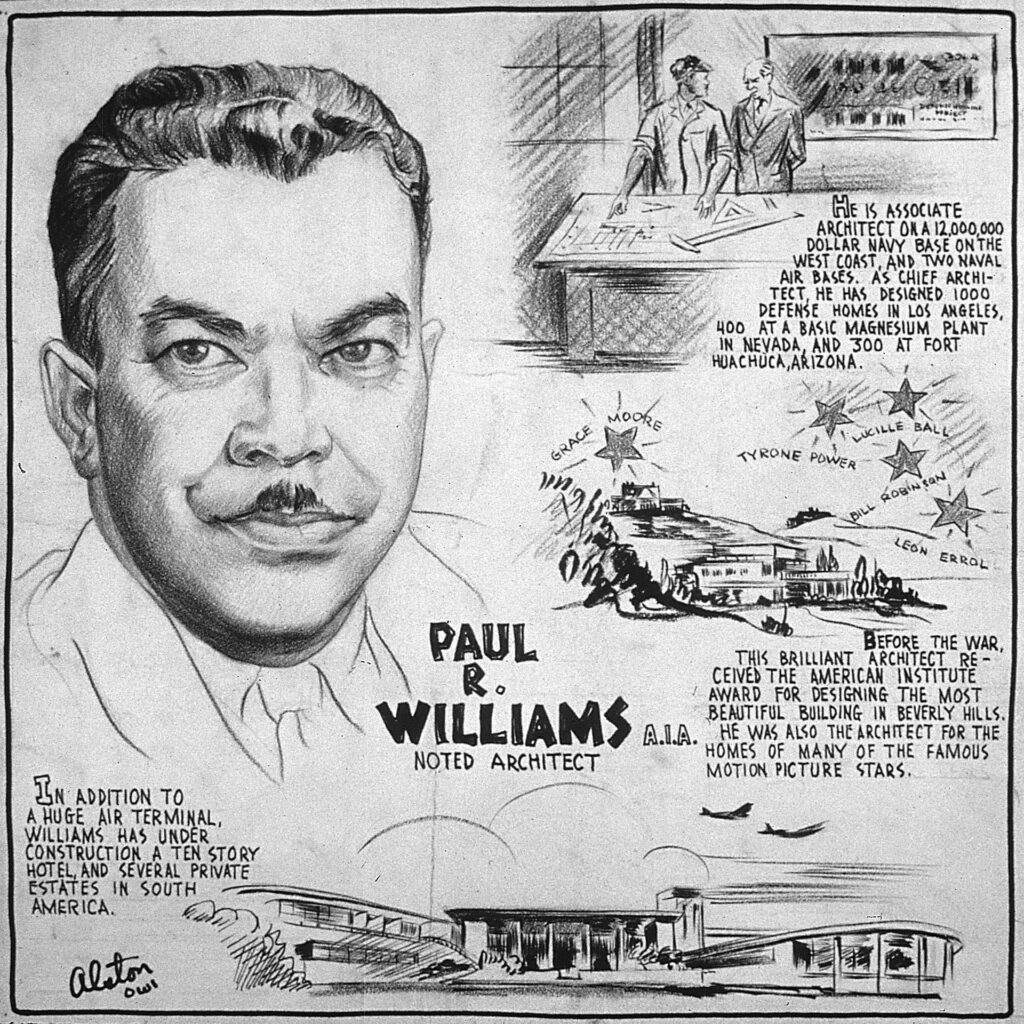

Exploring the entanglement of modernism and racism, our conversation turned to Paul Revere Williams, FAIA, one of Curry’s most passionate areas of research. Williams was an award-winning, Los Angeles-based Black architect who designed thousands of buildings—from practical public spaces to lavish residences for celebrities and power brokers—masterfully working across an array of styles and scales between the 1920s and 1970s. Notable projects include the famous Beverly Hills Hotel extension, the space-age Theme Building at Los Angeles International Airport, Frank Sinatra’s home in Trousdale Estates, and Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz’s home in Palm Springs. The sprawling mansion featured in the 1980s TV series The Colbys was created by Williams for Jay Paley, founder of CBS, and later owned by Barron Hilton of the hotel dynasty. Williams’ impact on LA’s distinct built-fabric endures to this day.

In an article entitled I Am a Negro, published in American Magazine in 1937, Williams described the overt racism he faced as a young Black man embarking on a career in architecture. “I came to realize,” he poignantly wrote, “that I was being condemned, not by a lack of ability, but by my color.” Curry noted the scope and range of Williams’ work is unparalleled in the history of American architecture. Williams became one of most successful architects in the country, despite the fact that he built venues like the Beverly Hills Hotel at a time when he wasn’t allowed to stay there.

Uplifting Williams’ important legacy has been Curry’s main occupation over the last few years. After collaborating with Williams’ granddaughter, Karen Elyse Hudson, to collate drawings, blueprints, photographs, correspondences, and other documentation, Curry orchestrated a joint effort between the Getty Research Institute and the USC School of Architecture (where Williams studied) to acquire and preserve Williams’ archives for posterity. Curry’s next big project is curating a comprehensive monographic exhibition of Williams’ work, scheduled to open simultaneously at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and USC’s Fisher Museum in 2026.

When Curry mentioned Williams’ belief that architecture can advance social progress, I was reminded of an inspiring theme running through Curry’s own work: the Citizen Architect. Curry offered a succinct explanation for this far-reaching concept in a recent Deem Journal interview: “Instead of coming in as the architect on that high horse, coming in as a fellow citizen who is trying to creatively utilize expertise to think about ideas alongside people who may have very different experiences and points of view.”

Beyond his numerous essays and lectures on the theme, Curry oversaw an innovative curriculum transformation during his tenure as Dean at USC School of Architecture aimed at training the next generation of practitioners and academics to be Citizen Architects. For Curry, architects have a significant role to play in making the world more equitable and sustainable. By creating spaces, systems, and platforms informed by empathy, inclusivity, and collaboration, architects can begin to level the unjust hierarchies underlying so many ills. The need for this kind of democratizing force, grievously, is as urgent as ever.

This article was published today in Forum Magazine by Design Miami/.