“Robert A M Stern—Bob to all who know him—has had an enormous impact on American architectural education. As Yale School of Architecture Dean, a position he held for 18 years, he expanded the breadth of the curriculum, invited many noted architects from around the world to teach, and empowered students to find their own architectural voice. He was not interested in students becoming mini-Bob Sterns any more than he wanted his faculty to become sycophants. He encouraged everyone to do their best, most rigorous work all the time.”

—Deborah Berke

Deborah Berke Partners Founder and Yale School of Architecture Dean

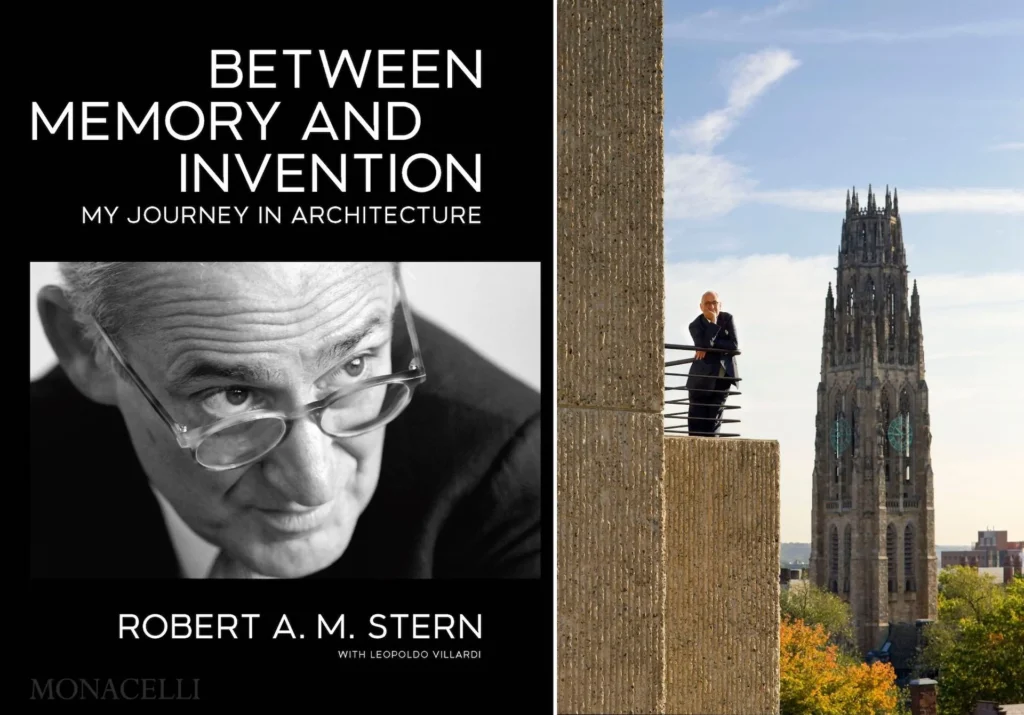

In the photo on the back cover of his new memoir Between Memory and Invention, Robert A M Stern casually leans into the balustrade of the penthouse-level terrace of Rudolph Hall, the home of Yale University’s School of Architecture. The Brutalist-style, hammered concrete building was designed by the building’s namesake and one of Stern’s mentors, modernist Paul Rudolph, in the 1960s. Dominating the background is Harkness Tower, part of Yale’s Memorial Quadrangle designed in Gothic-Revival-style masonry nearly a half century earlier. The Brooklyn-born architect, my guest last week for Architecture: The Legends, appears perfectly at ease between these two opposing forces: between tradition and modernity; between memory and invention.

The powerful book jacket photo encapsulates Stern’s august architectural career over the last 50+ years, which he has recounted so engagingly in this highly anticipated, much lauded autobiography. From private homes and highrise apartments to institutions, banks, and resorts, Stern’s prolific portfolio exemplifies the value of architecture that, in his words, “looks to the past while creating the present.” The photo further pays tribute to Stern the educator, in particular his many achievements at Yale. It’s where as a graduate student in the 1960s he learned to think like an architect and to write like a historian. It’s also where he went on to serve as Dean from 1998 to 2016, a legendary tenure that brought out the best in countless architectural minds active in the field today.

With extraordinary charisma and expertise, Stern held last week’s audience and me rapt as he took us through his fascinating journey—especially his dynamic relationship with New York City, where he founded his practice, now known as RAMSA, in 1969. Among the city’s most successful hometown architects, Stern’s distinct, “time traveling” structures have played a vital role in its prosperous real estate market. Outstripping demand for the city’s more futuristic skyscrapers, Stern’s limestone-clad residential towers evoke quintessential New York landmarks, such as his beloved Dakota, the River House, and Rosario Candela’s famous “set back” buildings from the 1920s. With a nod to historic precedents that line Central Park West, Fifth Avenue, and Park Avenue, Stern’s apartments prioritize spaciousness and quality, featuring amenities like walnut-lined libraries, screening rooms, and private restaurants. At a recent dinner party, a New York developer told me that RAMSA designs are expensive to execute but guaranteed to pay off, typically selling out even before construction begins.

Stern’s memoir, written with architectural historian Leopoldo Villardi, can be read as his love letter to New York. I had the chance to enjoy it over the summer while traveling in the Middle East and Europe. Though I was physically far from my Manhattan home, the book transported me to the amazing city that nurtured Stern’s special talents from a young age and led him through exhilarating circles of power and celebrity over the course of his career.

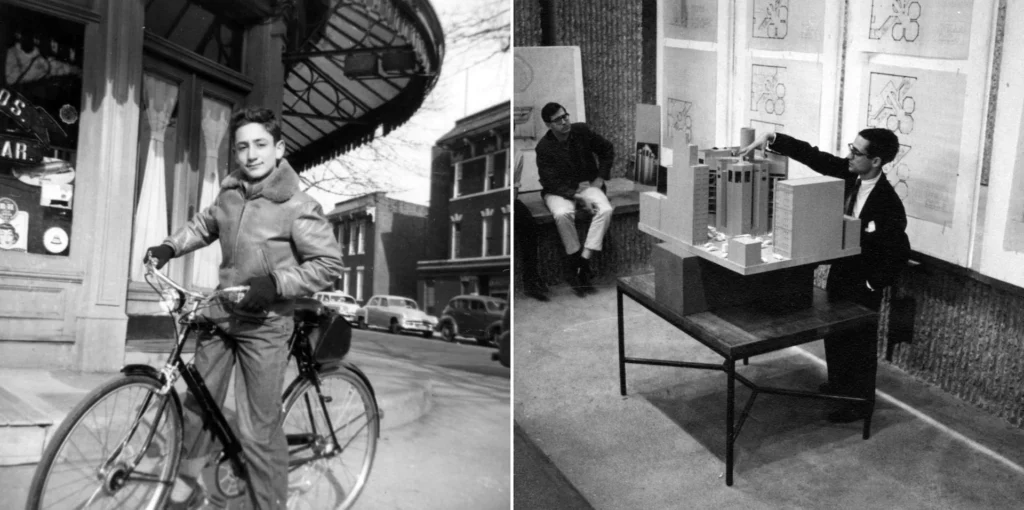

As a native New Yorker, Stern knows the city like the back of his hand and has had a frontrow seat to its oscillations between the gravitational pulls of enduring history (for better and worse, he acknowledged) and ever-changing novelty. He was born just three weeks before the opening of the World of Tomorrow, the thematic title of the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Pushed in a stroller by his parents, he was among the 44 million who attended this historic celebration of heroic optimism and the thrill of the new. In the postwar boom years, the city’s character began to shift as progress took the shape of cookie-cutter buildings. By age 12, he knew he wanted to be an architect, but he didn’t yet imagine his work would transform New York’s epic skyline.

As Stern came of age and was able to explore the world beyond New York, his passion for the ordered beauty of classicism fully emerged. One of the most aesthetically formative moments of his life occurred on his first trip outside the US, on his honeymoon in Milan. There the young architect was indelibly etched by Ca’ Brutta, a neoclassical apartment house designed by Giovanni Muzio in 1920. Its balanced form and proportions, he told us, remained bright in his memory as his practice developed.

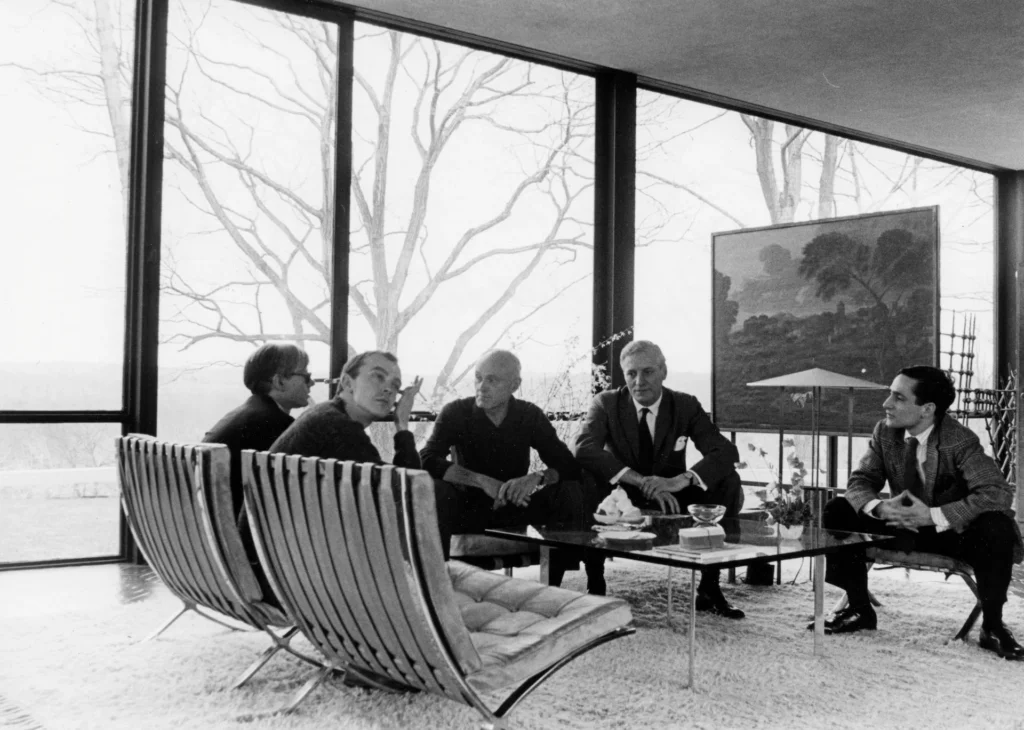

Stern’s oeuvre shows traces of another expression of classicism as well: early American architecture. Through the teaching of another important mentor, historicist and preservationist Vincent Scully, Stern discovered the allure 18th- and 19th-century New England vernacular forms and would go on to revive the chic yet informal symmetry and traditional motifs of the Shingle Style. Recognizing the weight of his influence, Stern described Scully as “a wonderful person” and “a major force in architecture and education,” who along with Robert Venturi, another mentor, was instrumental in legitimizing the rejection of modernism, paving the way for Stern’s own career.

Stern’s first position out of school, I was surprised to learn, was not as a practicing architect, but rather as a fellow at the Architectural League of New York. There, in 1966, he curated an exhibition and accompanying catalog, titled 40 Under 40, which included what would become, the following year, his first built house: the Wiseman House in Montauk. This shingled and gabled design turned out to be Stern’s springboard, the career-making prototype for a long series of coastal single-family homes that Stern went on to build in Eastern Long Island. By the 1980s, Stern’s Shingle Style homes had become (and remain to this day) the most fashionable and desirable in the region.

The projects that Stern takes on largely come from his close relationships, aided by his knack for converting strangers met at social events ino repeat clients that commission house after house and connect him to others in their networks. One example is Michael Eisner, Former Chairman and CEO of The Walt Disney Company, for whom Stern designed personal homes as well as sprawling commercial complexes like Disney’s BoardWalk and Yacht and Beach Club Resorts in Florida.

“I’ve been impressed since Bob Stern designed my parents’ apartment in the 1960s, with its greenhouse for the dining room,” Eisner told me. “But I’ve grown even more impressed each year since, as he has been the architect on multiple buildings and hotels around the world for Disney and for others. As a Disney board member, Bob kept us on the right brick-and-mortar creative path. And nothing is more exciting than traveling the world with Bob looking at architecture… Reading his books is one thing, but being in his head on the road is another.” Stern, in kind, praised Eisner and other developers like William and Arthur Zeckendorf and Stephen Ross for championing architectural innovation—for taking the risks and hiring architects who think outside of the box.

To the audience’s great amusement, Stern generously shared a few anecdotes about the clients who didn’t hire him. After acquiring an apartment in Stern’s San Remo Towers in New York, Steve Jobs approached Stern about doing the interiors. Ultimately, Job’s gave the project to IM Pei, who famously contributed to iconic elements of Apple Stores. Another missed opportunity was Barbara Streisand, who wanted Stern to create her new home in Eastern Long Island. As he proudly drove her around in his convertible to tour sites, the singer noticed the CDs in his glove box did not include her work—and that was the end of their short but memorable relationship.

As last week’s conversation drew to a close, Stern broached a subject that currently has the international architectural community in heated debate: the remodeling or destruction (depending on whom you ask) of the Sainsbury Wing of London’s National Gallery. Designed by Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown and completed in 1991, the original structure is one the world’s most treasured examples of postmodern architecture. The institution ostensibly commissioned the changes to meet evolving needs. But like so many other committed preservationists—including UK-based English Heritage, Historic Buildings and Places, and the Twentieth Century Society—Stern characterized the proposed plans as “brutal” and “one of the most urgent preservation issues of today.” He listed for us a number of alternatives that the National Gallery should consider before irreversible erasure is done. The overarching lesson that Stern left us with is that memory cannot not be sacrificed for invention. The value of one is equal to the other.

This article was published today in Forum Magazine by Design Miami/.