“Ever since I saw The Spiral—Daniel Libeskind’s 1996 proposal for the V&A Museum extension—I have felt totally inspired by his work. His juxtaposition of a Cubist facade with the 19th-century classical building was a contemporary statement of our time. He opens new ideas in architecture to move our visual experience forward.”

—David Gill, David Gill Gallery

On September 9, 2001, Daniel Libeskind felt that he had achieved a truly meaningful milestone. The significance of the moment, both personally and professionally, rushed over the Polish-American architect—the child of Holocaust survivors—as he was seated next to his wife and partner Nina in the historic Berlin State Opera House listening to Israeli-Argentine Daniel Barenboim conduct Gustav Mahler’s Symphony #7. The piece is one of the Austro-Bohemian Romantic composer’s most complex works, representing an epic journey through night, from dusk to dawn. The concert was part of the opening gala of the new Jewish Museum Berlin, which Libeskind had designed to illuminate the centuries-long history of the Jewish people in Germany, memorialize their immense suffering, and celebrate their enormous intellectual, economic, and cultural contributions to the world.

As Libeskind shared this touching memory during last week’s Architecture: The Legends program, I found myself reflecting on the many fateful events that have impacted his monumental career. Such as how Berlin’s original Jewish museum was founded in 1933, just six days before the Nazi’s seized power and ordered the Gestapo to shut down the institution and confiscate its holdings. Berlin became the base from which the Nazis planned the Holocaust, which thrust Libeskind’s parents into a Soviet forced-labor camp. Like so many Holocaust survivors after the war, Libeskind’s family (with him in tow) emigrated to Israel and finally New York City in search of a better life. Decades later in 1989, mere months before the fall of the Berlin Wall, Libeskind won the competition to design the Jewish Museum Berlin, even though the 40-something architecture professor had never built anything. Following 13 fraught years of negotiations and construction, the glorious opening finally arrived—less than 48 hours before the tragic 9/11 terrorist attack, which would lead him to another politically challenging yet ultimately triumphant memorial project, the master plan to rebuild the World Trade Center at Ground Zero.

A transformative, career-making project, the Jewish Museum Berlin embodied what would become his signature architectural vision. The design strikingly integrates old and new, augmenting the site’s existing 18th-century former courthouse with a dynamic, zigzagging structure meant to symbolize the story of Jews in Germany. The sharp angles are reminiscent of another Berlin masterpiece—an exemplar of German Expressionist architecture beloved by Libeskind—Mies van der Rohe’s Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht Monument to the Revolution, built in 1926 and demolished the following decade by the Nazis. For visitors to the Jewish Museum Berlin, the experience is emotional, unforgettable, and immersive, as would become a Libeskind hallmark. My first tour of the museum structure—before the collections had been installed—left me flooded with personal memories and overcome by the painful expulsion, destruction, and loss of life in the Shoah that came to shape my own family’s fate.

Widely considered the poet of contemporary architecture, Libeskind draws inspiration from a range of artforms to create residences, towers, and institutions richly layered with moving narratives. Architecture, he told us, is not only about beautiful structures, but also about forging connections and eliciting emotions. He cited his admiration for William Shakespeare’s and Emily Dickinson’s optimistic expressions of the “rich, mysterious, and exquisite notions of life,” as well as, in his words, the “architectonic” compositions of Baroque master Johann Sebastian Bach. “Creating a building is like writing books,” Libeskind told us. “Every word matters.”

A similar sentiment is found in the lyrical opening lines of Libeskind’s 2004 memoir Breaking Ground: “Someone once asked Goethe what color he liked best. ‘I like rainbow,’ he said. That’s what I love about architecture. If it’s good, it is about every color in the spectrum of life; if it’s bad, the colors fade away entirely. From the ruins of Byzantium to the streets of New York, from the peaked roof of a Chinese pagoda to the spire of the Eiffel Tower, every building tells a story, or better yet, several stories.”

Philip Johnson once told Libeskind that he recognizes good architecture when he feels it in his stomach. Libeskind said he “feels” it when he sees the contemporary architecture of Norman Foster and Frank Gehry. The feeling also arises, he said, from all manner of historical treasures, including, to name a few, the ancient Pyramids at Giza in Egypt; the Wieliczka Salt Mine near Kraków (first developed in the late 13th century); the vernacular farmhouses at the Norsk Folkemuseum outside of Oslo (14th-19th centuries); Sir John Soane’s House Museum in London (c. 1808-24); Erich Mendelsohn’s Einstein Tower in Potsdam (1921); and Le Corbusier’s Notre-Dame du Haut Chapel in Ronchamp (1955).

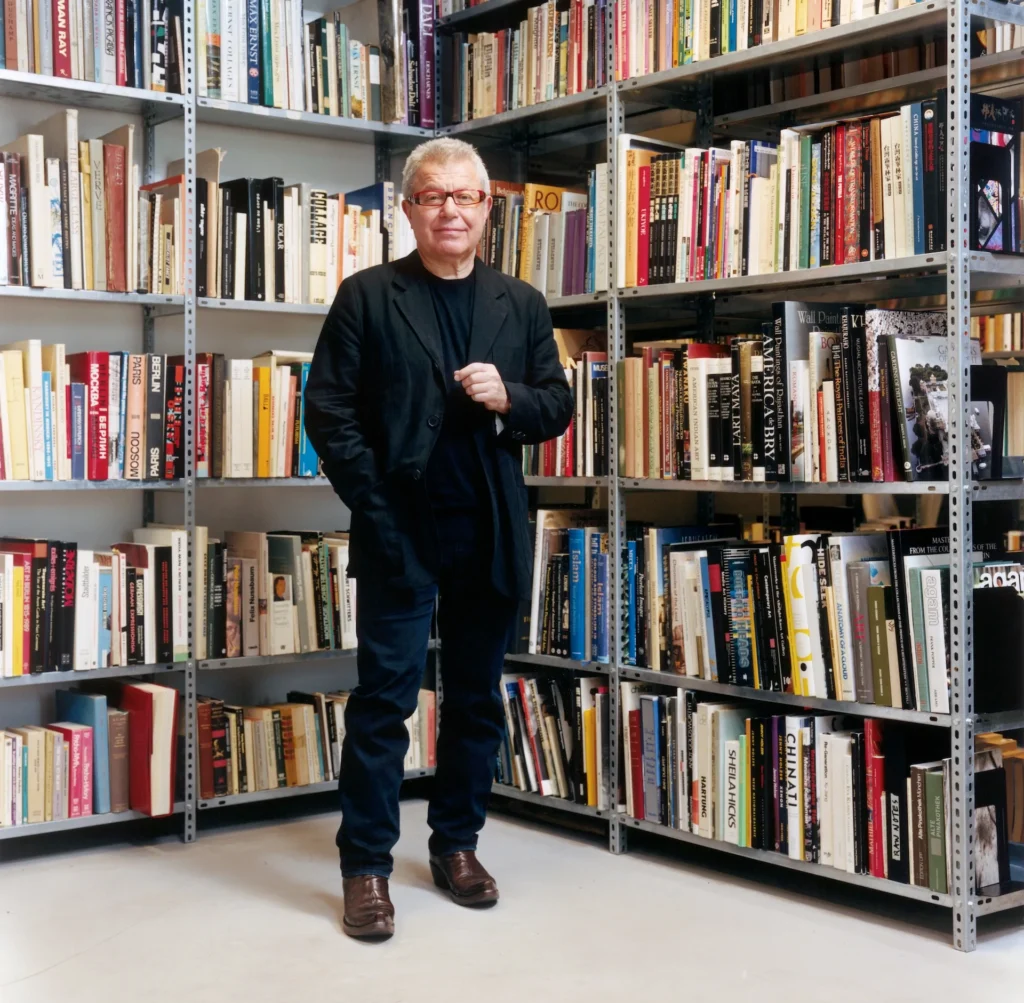

Libeskind applies his emotive, storytelling approach across scales and has become as passionate about furniture as architecture since he designed the Spirit House Chair for his 2007 extension of the Royal Ontario Museum. “Designing a chair,” he added, “can be more challenging than designing a building.” Most of Libeskind’s intricately handcrafted furniture has been produced in collaboration with esteemed London-based gallerist David Gill and the finest artisans in Italy and the UK. Gill confirmed that Libeskind is personally very hands-on throughout the process, down to the smallest detail. “In designing furniture,” Gill said, “Libeskind’s forms carry the same force as in his buildings, always offering a unique element of surprise that makes you look anew.”

Libeskind is currently building projects in 20 countries around the globe. As his portfolio of exciting commissions has grown, though, he has continued to hold a special place in his heart for his work in New York City. He can still clearly picture, he told us, the energetic skyline as he arrived in New York Harbor by ship early one morning in 1959. He fondly recalls the optimism that he and his family felt at the sight of New York following their long voyage from Israel, which was preceded a few years earlier by their flight from Poland, where Libeskind had lived the first decade of his life. His immigrant identity and his family’s journey from tragedy to optimism, he said, played an essential role 40 years later as he developed the Ground Zero master plan.

One of the largest, most high-profile architecture competitions the world has seen, the momentous project came to Libeskind through a fateful series of events, set off by the thoughtful insights he shared during a panel discussion on the future of Ground Zero at the 2002 Venice Biennale of Architecture. Invited to join the competition’s jury as a result, Libeskind asked to submit a design proposal instead. As an immigrant welcomed by New York—who grew up in public housing in the Bronx before receiving a prestigious, tuition-free education from the Cooper Union in Manhattan—Libeskind wanted to do more for his adopted home than just leave his mark on the iconic skyline. In Libeskind’s sensitive hands, a site of profound loss became a cherished place of memory, where the victim’s and their families are forever honored amid a powerful statement of reinvention and renewal. It was a project, it seems, that Libeskind was born to do.

This article was publsihed today in Forum Magazine by Design Miami/.

Zlota 44 in Warsaw by Studio Libeskind, 2017. Photo © Krzysztof Wierzbowski.

I always like hearing Libeskind speak, and own (but ironically have yet to read) Breaking Ground. Your quote that a building is like a book – every word is important – reminds me of something Libeskind said in a lecture at the Bartlett in London (I was doing my diploma at U. Westminster just up the road and would slip into lectures at the AA and the Bartlett), he told us, the audience, Read, it doesn’t matter what, just read.

Anyway, thanks for this article, I’ll read your work more!

PS: I now recall that I saw him speak at the Royal Academy, not the Bartlett…