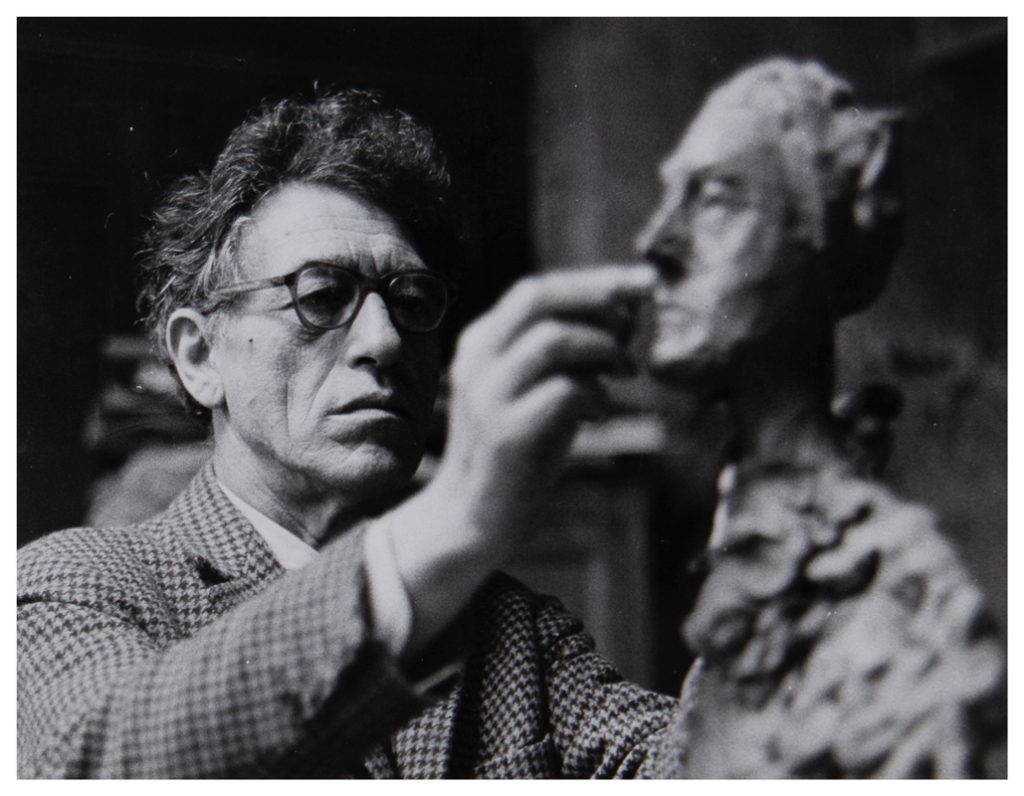

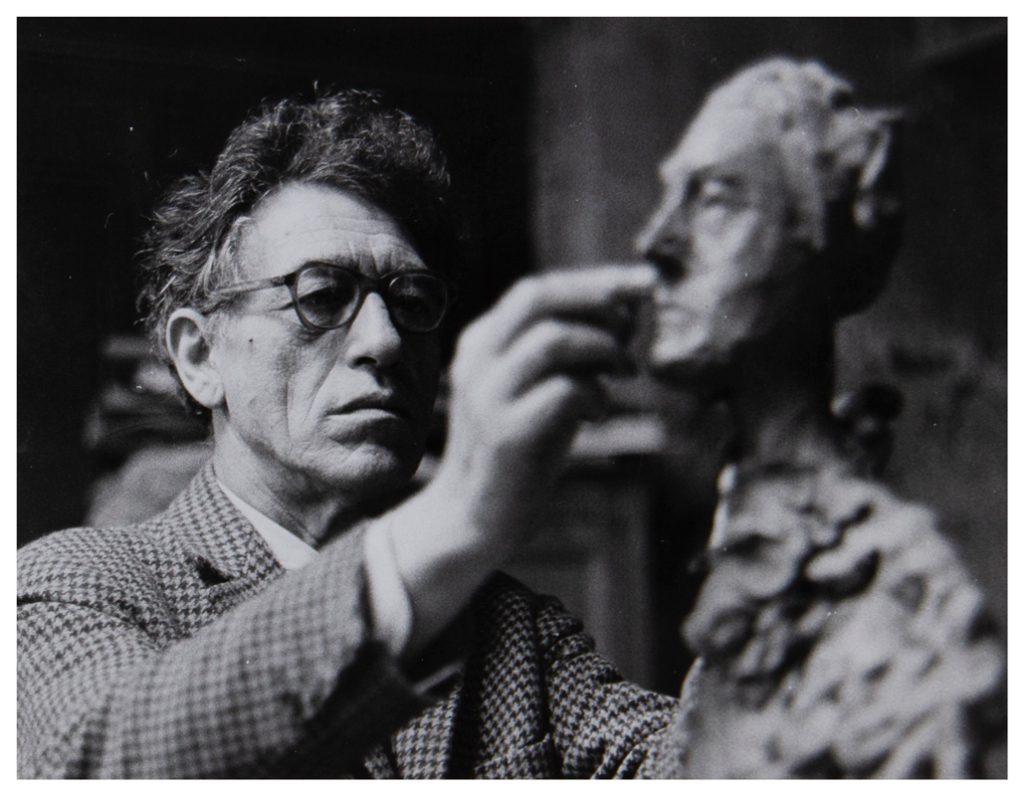

There is a great deal in common between modernist architecture and the work of Swiss artist Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966), with the most obvious being the similarity of their philosophies regarding humanity. Both placed the human experience as their main point of reference and key subject. When the two coincided, new layers of aesthetics and conceptual experiences revealed themselves—as famously seen at the Beyeler Foundation Museum (designed in the 90s by Renzo Piano) and at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art (designed in the 50s by Vilhelm Wohlert and Jørgen Bo). Now this triumphant juxtaposition is presented in all its glory at the inaugural exhibition, Alberto Giacometti: Beginning, Again, at the most exciting cultural event in Tel Aviv: the reopening of the Eyal Ofer Pavilion, an annex of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art.

Alberto Giacometti has not frequented Israel, but the 130 works on view (sculptures, drawings, photographs, and sketches), mostly on loan from the Foundation, taking up the entire building, and marking of his 40-year Parisian career, is a real local sensation. I have seen retrospectives and monographs of the Swiss artist before, but this event is an extraordinary visual experience; the way that the work and the architecture complement each other is exquisite.

Giacometti’s remarkable career came to represent the shifts in the European avant-garde; from Surrealism, to Existentialism, to his unique figurative work, as he helped developing the motif of the suffering human figure into a popular symbol of post-war trauma. Similarly, the architects who built Tel Aviv during the interwar and postwar years perceived modernism as an agent of change that represented the rebuilding of a Jewish home to immigrants who had long suffered from antisemitism before and during the time of Nazi-occupied Europe.

I had the honor of getting a private tour of the newly-renovated pavilion from its architect, Amnon Rechter of Rechter Architects—a friend of mine as well as the son and grandson of the architects who created the building (together with Dov Karim). It was commissioned in 1952 and originally named the Helena Rubinstein Pavilion after the renowned founder of the eponymous cosmetics empire, whose foundation made the construction of the pavilion possible, and opened in 1959.

Yaakov Rechter (1924-2001), the second generation of the renowned family of architects was Israel’s most celebrated architect of the 70s, being responsible for some of the country’s most important hospitality, cultural, and public architecture. The pavilion was planned to be part of a cultural hub in Tel Aviv, created in the late 50s to include the National Theater, the Israeli Philharmonic music hall, and the Yaacov Garden—a secret gem filled with perennials and two giant Ficus sycomorus, which have since come to symbolize classic Tel Aviv.

As the pavilion was devoted to small, avant-garde exhibitions of contemporary art, during its 60-odd years of existence it has been changed and modified to the curatorial requirements of the time. In recent years it has been gloomy, run down, and disconnected from both the original building and the current direction of exhibiting art; it was time for a facelift. This is when Rechter was brought in to begin planning and rethinking how to modify the building to meet the 21st century.

He was able to completely reconfigure the interior, transforming the space to be wide, white, and crisp, embodying many of the principles initiated by his grandfather, Zeev Rechter; one of the few modernists that brought the message of modern architecture to pre-state Israel. He turned a brutalist building into a modernist one — airy, open, transparent — an homage to the ‘White City,’ as Tel Aviv has come to be referred to due to having the highest concentration of modernist buildings that helped determine its historic fabric, reveal its glory, and extend its integrity. The split-level plan allows for an open space, while also letting the viewer see the majority of the pavilion from nearly every angle. The current show presents 130-work exhibition which illuminates Giacometti’s achievements in his early and figural art, capturing the alienation, fear, and uncertainty during a time when the entire art world went abstract, a magical marriage of art and design.