I love exhibitions that explore connections between visionary artists who never met, but whose art and oeuvre have multiple common chords. The recent show in this manner was opened last week at the Columbus Museum of Art, entitled Wild Earth: JB Blunk and Toshiko Takaezu, comes to explore the parallels between these two American artists whose contribution to modern design has been widely explored by never in this context and in relationship both had to the Japanese Mingei Movement. I have visited Takaezu’s home and studio in New Jersey, but even though I have never been to Blunk’s home studio in Northern California, knowing it from photographs, I can see the parallel.

The exhibition, curated by Daniel Marcus, the Museum’s Curator of Collections and Exhibitions, stages a dialogue between Blunk and Takaezu’s handmade worlds, revealed through artworks ranging in scale from monumental ceramics and woodcarvings to delicate jewelry. We learn that both drew striking parallels throughout their lives and their work. Tracing their paths to and from Japan, both had a shared commitment to handmade arts, rural lifeways, and an environmental consciousness rooted in the land.

In 1953, the young ceramicist JB (James Blain) Blunk turned up unannounced at the workshop of Kaneshige Tōyō, a master Japanese potter who lived and worked in the rural Okayama Prefecture. A chance encounter with Japanese American sculptor Isamu Noguchi had secured Blunk’s entry into the Japanese pottery world, leading him to seek Kaneshige’s mentorship. Reluctant at first, Kaneshige agreed to host Blunk as an apprentice, teaching him to produce Bizen ware—an art of unglazed, wood-fired clay prized for its rustic beauty.

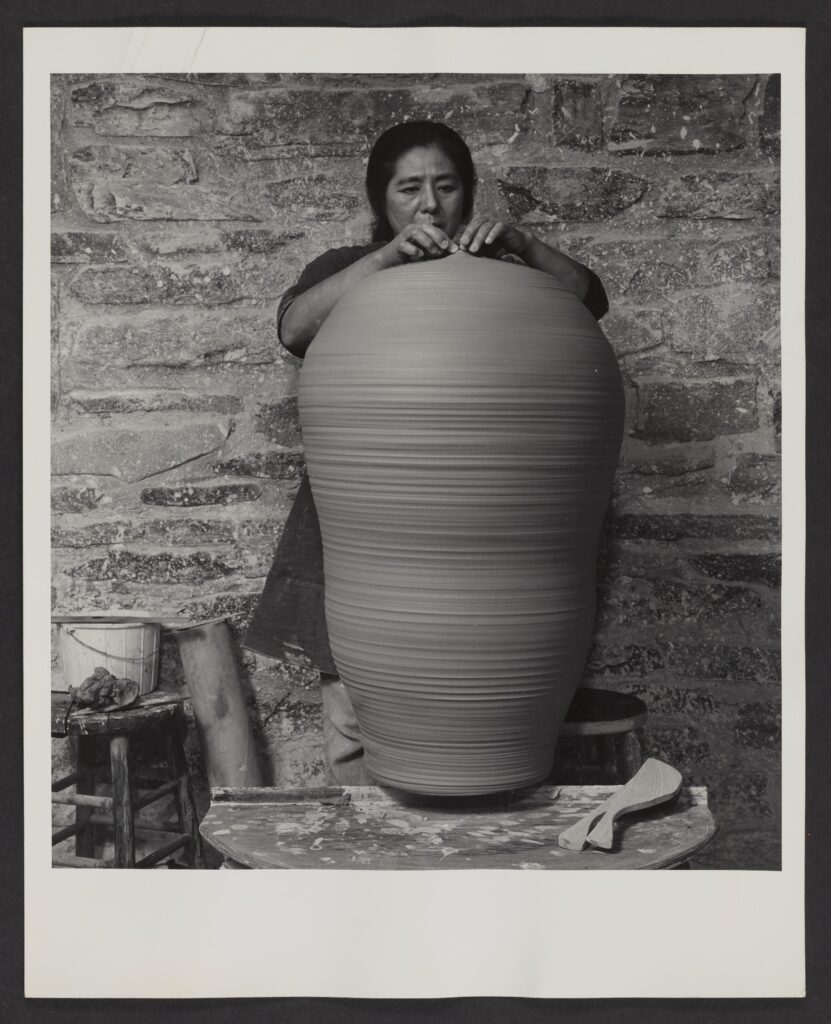

Soon after Blunk’s apprenticeship ended, another American visitor arrived on Kaneshige’s doorstep: Toshiko Takaezu. Born in Hawaii to a family of Okinawan Japanese immigrants, Takaezu had already established her reputation as a professional potter and was about to begin a teaching position at Cleveland Institute of Art. During a six-month excursion across Japan from 1955-56, she met with numerous ceramicists, including Kaneshige, whose philosophical commitment to pottery left a mark on her. She returned to his studio to practice on his wheel, becoming one of the first American women to gain access to this rarefied—and thoroughly male-dominated—craft culture.

Following her Japan trip, Takaezu took an increasingly experimental approach to ceramics, embracing accidents and imperfections in her clay bodies and favoring closed forms without obvious functionality. In 1964, she moved from Ohio to rural New Jersey, where, aided by live-in apprentices, she made increasingly large closed vessels, treating the pot’s exterior surface as a three-dimensional canvas. Each winter, Takaezu returned to Hawaii to reconnect with family and the landscapes of her childhood; these journeys informed many of her most ambitious and experimental works, from sculptural trees to glazed vessels evocative of the Pacific Ocean. So did Takaezu’s garden, a focal point of her daily activity and frequent source of inspiration.

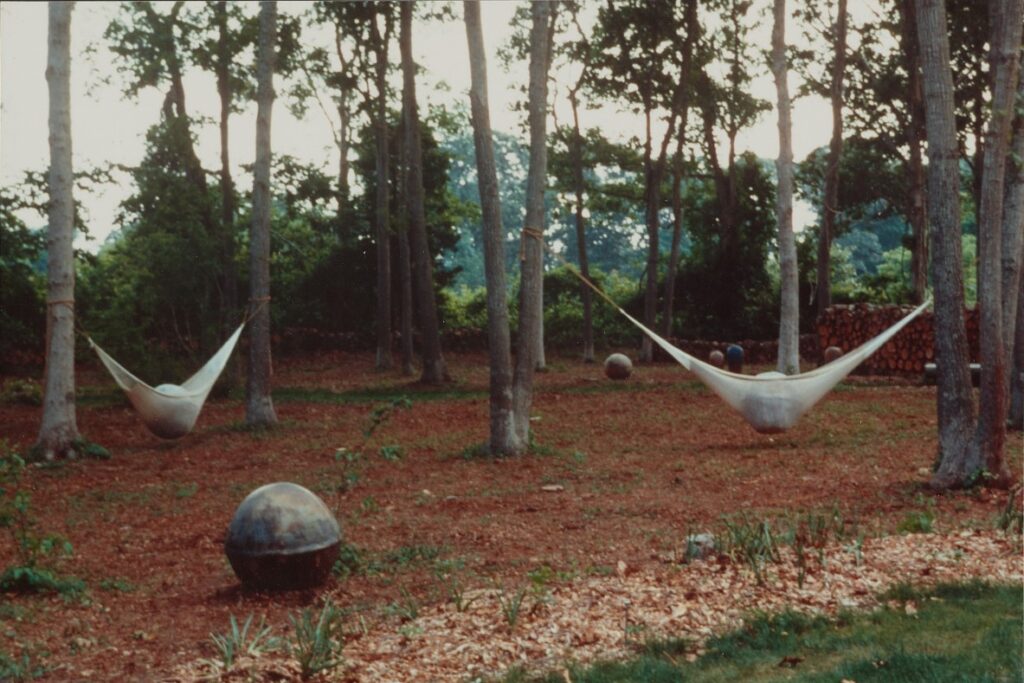

Like Takaezu, Blunk also chose to live and work in the backcountry, settling on a hillside in Northern California, where he and his first wife built their home by hand. Later lauded as his magnum opus, Blunk’s house sparked his exploration of materials beyond clay. He came to treat the chainsaw as his main creative instrument, creating large-scale sculptures from timber salvaged from logging sites and along the shoreline. He also carved and polished stones found in local rivers and along the Pacific coast and continued to practice ceramics alongside painting and jewelry. Committed to living lightly on the land, Blunk described his hand-made home as “one big sculpture,” the central focus of a life dedicated to making—and making do.

Although Blunk and Takaezu never met, both upheld artistic autonomy as a supreme value, while refusing the binary opposition of fine arts versus crafts. Anticipating the principles of the back-to-the-land and do-it-yourself movements, both artists sought to live and work in tune with the non-human environment, and to center the land in their work. At the same time, Blunk and Takaezu each knowingly employed technological instruments and industrial materials, harnessing their destructive capacities—from the noxious fumes and noise of the chainsaw to life-threatening glaze chemistries—to create works of otherworldly beauty and surprising utility.

The exhibition will be on view through August 3, 2025.

© Family of Toshiko Takaezu. Photograph by Christopher Gardner.

©Family of Toshiko Takaezu.

Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Gift of the Artist. ©Family of Toshiko Takaezu.